Fixed Credit vs. Fixed Delta

Posted by Mark on April 15, 2016 at 07:08 | Last modified: March 22, 2016 10:13The issue of fixed credit vs. fixed delta has come up a couple times recently including the previous blog series.

I used fixed credit when backtesting naked puts. Fixing credit rather than delta means short delta decreases as the underlying price goes higher. This boosts probability of profit (PP).

Fixed credit may be apples-to-oranges because an increased PP over time means fewer losses. This will likely result in more linearity to the equity curve as underlying price increases. In other words, as time goes on the system may work better for no reason attributable to the strategy itself. Compared to fixed delta, I am effectively trading smaller and more conservatively with the end result serving to retain profits I already have.

Because of the similar feel, I wonder if this is another form of apples-to-oranges comparison: variable position sizing. This would be a definite no-no in trading system development. Number of contracts remains constant throughout. Max loss per contract remains constant throughout. Only when I looked at capital risk did I see the variability. I would be interested to analyze capital risk over time with fixed delta to compare.

While fixed credit may seem like apples-to-oranges, the pursuit still seems defensible to me. Without question, I want that linear equity curve. If fixing credit generates a linear equity curve then have I cheated by allowing the probabilities to increase over time? Intuitively, I feel a higher PP and concomitant lower credit may mean larger net losses when the market suffers significant corrections. This disadvantage to fixed credit should even the score.

Whether the magnitude (%) of corrections is correlated to underlying price is a different study altogether. I could probably attempt to analyze this but I have a very small number of market corrections to sample. Since the financial crisis, we had the Flash Crash (2010) and the Fiscal Cliff (2011), but then nothing until fall 2014 and the two recent 10% corrections of Sep 2015 and Jan 2016.

In summary, I like what I see with fixed credit but remain uncertain about its validity. While it seems semantically valid (“remains constant throughout“), the effect of the fixed numbers is analogous to variable position sizing and that is what troubles me. Completing the fixed delta backtesting must be done to answer some of these questions.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | PermalinkOn Discretionary Trading (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on February 23, 2016 at 07:23 | Last modified: January 20, 2016 10:47I mentioned previously what recently got me thinking about discretionary trading.

I believe discretionary trading to be something between the pot of gold on the other side of the rainbow and a salesperson’s best friend for life. While markets may not be completely random or predictable, we can test an idea on all the data available to us and then imagine a drawdown worse than anything seen historically. The inability to quantify this hypothetical future drawdown may be the only source of unknown risk from a valid system development methodology.

Discretionary trading involves lots of unknown risk that falls in the “don’t know what you don’t know” category. People seem to be easily convinced that discretionary guidelines are a plausible way to learn profitable trading. In reality, discretionary trading is highly susceptible to heuristic thinking, cognitive bias, and logical fallacy. Unlike discretionary traders, experienced system developers take exhaustive steps to avoid things like the confirmation bias, the fallacy of affirming the consequent, the fallacy of the well-chosen example, insufficient sample size, and curve-fitting.

I cannot prove that discretionary trading does not work but I have seen two clear-cut phenomena. First, profitable trading strategies in select communities are all the rage until they stop working by which point other strategies have become the focus. Second, many popular, outspoken traders disappear from public view over time. Did they get bored and stop trading? Did they switch communities like snake oil salesmen moving to the next town? Did they strike it rich from trading and retire? Did they suffer catastrophic loss and go quietly into the night?

When catastrophic losses occur, excessive position sizing can always be blamed instead of discretionary trading itself. To those who insist on keeping position size small I always raise the issue of how one can possibly generate requisite profits to cover the monthly living expenses. “Trade small” is theoretically invincible as a strategy to avoid Ruin but whether it can practically work for anyone is a very individualistic matter that is rarely addressed in public.

Hobby/part-time traders never hoping to do so as a business can probably trade discretionarily in small size with impunity.

Categories: System Development | Comments (2) | PermalinkOn Discretionary Trading (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on February 19, 2016 at 06:52 | Last modified: January 22, 2016 10:12I suspect these are not going to be new thoughts on discretionary trading but they are the first I’ve had in a while.

I feel my approach is more unique than my trading strategies. The former is based on system development whereas the latter can be found in trading books anywhere.

Despite going through the 15-year database twice, I am not done with naked puts. I have a large sample of trades and historical context for expected returns in good times and in bad. Much data analysis remains to determine whether any hidden edges exist but I’m happy with the conceptual framework developed thus far.

We had a good trading group meeting the other night where two new strategy variants were discussed. When it comes to discussing a trade or strategy, my mind immediately goes to system development. Is it something that can be operationally defined? If not then where are the holes? How much of a pipe dream are we actually considering?

After naked puts, a butterfly trade is the next place I would like to channel my efforts. I’ve given this some thought and had trouble defining the strategy in simple and limited steps. I generally find too many degrees of freedom for a systematic approach. Perhaps this is more suited as a discretionary trade with loose, general guidelines.

The problem is that I remain very skeptical about discretionary trading. Some of my old ideas may be read here, here, and here. In the next post I will start to describe my current philosophy.

Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkRisky Proposition (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on January 29, 2016 at 06:50 | Last modified: February 1, 2016 11:25I believe we should always be thinking about the likelihood of history to repeat before concluding too much from historical backtesting. Usually, the answer is “unlikely to repeat” and Monte Carlo simulation to randomize trade sequence seems like a logical solution. Studying only one historical equity curve introduces selection bias to the system development process.

Lines 4-6 in the last post suggested dividing initial equity by the maximum drawdown (DD) to best understand trading system risk. This prevents someone from inflating potential returns by advantageously changing the backtesting start date. Certainly when developing my own system I also want to avoid underestimating risk. In live trading if I lose much more than expected then the result could be catastrophic.

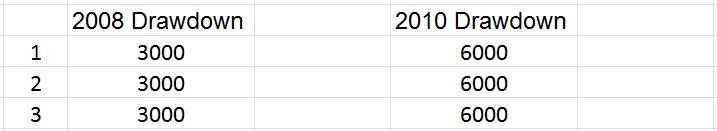

Lines 1-3 address accurate assessment of DD risk. I love to see an equity curve grow exponentially but the way to do that is by increasing position size along the way. DDs occurring later in the trade sequence will be proportional to position size and this can distort our understanding of risk. For example, which year has the worst DD for each system shown below?

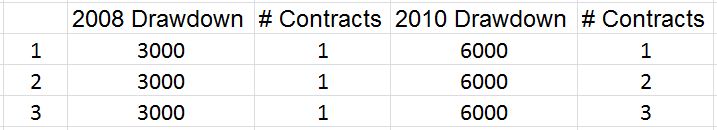

Clearly the 2010 DD is twice that of 2008 for each system. Does the additional information shown below change your perception?

The 2010 DD is worse for system 1, the 2008 DD is worse for system 3, and the DDs are equivalent for system 2. I now can better understand how DD should be understood in terms of position size.

Using a constant position size during development of a trading system helps remove the bias produced by order-dependent testing results. We may already have a selection bias introduced by choosing an equity curve that is better than the mean. Do not compound that by adding artificial equity growth due to trade sequences not likely to be repeated.

Put in simpler terms, when analyzing DDs I need to keep position size constant to ensure apples-to-apples comparison.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | PermalinkA Brief Glimpse into Theoretical Physics

Posted by Mark on January 26, 2016 at 04:07 | Last modified: December 10, 2015 09:45Last time I mentioned a concept arguably more suitable for a theoretical physics blog than a blog on option trading:

> To say “calculate [drawdown] as if it happened on Day 1” is to

> say any ordering of events is equally likely. A 2011-type

> correction could have just as well happened in 2002 and a 9/11

> could have just as well happened in 2008, etc.

Understanding our current reality as a cumulative result of historical events/decisions is a controversial interpretation amounting to fate and destiny. While many people do understand the world in these causal terms, cognitive psychology suggests the human brain works unconsciously to identify causation even where none actually exists. This is adaptive: living in a logical world is certainly less stressful than living in a world where utter chaos lurks around every corner.

How robust is our current reality? Is it like a sequence of dominoes where toppling of just one can affect everything that comes after? Is it more like Jenga where many previous decisions may be altered before the present is affected?

Trekkies will always remember the words of Jean-Luc Picard in “Yesterday’s Enterprise:” “Who is to say that this history is any less proper than the other?”

Another good description of the infinite realities concept is shown here from time index 07:00 to 09:45.

For all these reasons, I mentioned “overstated conclusion” in the final paragraph. I do not want to make the mistake of basing trading decisions on the shape of a backtested equity curve. People commonly ask to see these historical equity curves without realizing that these are just one possible path a trading system may follow through time. A slight alteration in the trade sequence may result in worse drawdowns, losing periods instead of profitable ones, etc.

Gaining that “broader perspective” by numerous Monte Carlo simulation runs can decrease the chance of falling prey to this sort of curve-fitting.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | PermalinkRisky Proposition (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on January 25, 2016 at 07:03 | Last modified: December 8, 2015 15:38Continuing on with a previous discussion about normalizing risk:

> Position sizing should be held constant throughout the [1]

> [duration of in-sample backtesting]… This allows for

> an apples-to-apples comparison of PnL changes [3]

> throughout… A drawdown (DD) at any point should be

> evaluated as if it occurred from Day 1; this is one [5]

> way of interpreting maximum risk.

I will start by describing the concept in lines 4-6 and then cover lines 1-3.

Risk tolerance may be used to determine position size. Suppose the max DD I can psychologically withstand is 10%. Based on the oft-quoted trading adage “the worst DD is always ahead of you,” I should select a smaller position size such as one corresponding to a max DD of 5%. If I now encounter something 2x worse in live trading, my psychology can [hopefully] tolerate it thereby avoiding the potentially catastrophic result of abandoning ship at the darkest moment.

Sticking with the conservative theme, I should also calculate DD as a percentage of initial equity because this will give a larger DD value and a smaller position size. For a backtest from 2001-2015, 2008 was horrific but as a percentage of total equity it might not look so bad if the system had doubled initial equity up to that point.

To say “calculate DD as if it happened on Day 1” is to say any ordering of events is equally likely. A 2011-type correction could have just as well happened in 2002 and a 9/11 could have just as well happened in 2008, etc. In case this is true, I prefer not to trade real money based on the overstated conclusion that a DD occurring later was destined to occur later. Monte Carlo simulation can randomize the trades to generate a large number of potential trade sequences for a trading system. I can then look at averages and standard deviations for things like net income and max DD to get a broader perspective of what to expect in live trading.

Categories: System Development | Comments (3) | PermalinkAn Argument for Statistics (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on December 21, 2015 at 07:09 | Last modified: December 7, 2015 14:43In my opinion, trading system development is similar in importance to hypothesis testing and inferential statistics in addition to being something most traders don’t know much about.

Aside from my familiarity with statistics, I am a student of trading system development. Trading system development looks at measures related to profitability, consistency, drawdowns, and much more.

While I find this all interesting and potentially very useful, at the outset maybe I just want to know if my system is better than trading at random. Maybe I just want to know if my system is better than zero profitability. These are questions that lend themselves to inferential statistics because the null hypothesis would say “the system is not profitable.”

In the final analysis, I think we have at least two different approaches to trade validation. One approach involves hypothesis testing and inferential statistics. Aside from those with research backgrounds of some sort, I’m not sure who might think to employ statistics for this purpose. I think trading system development is more popular among algorithmic traders and those employed in finance since it uses parameters and jargon created specifically for the industry.

Perhaps the two are accomplishing the same thing but from completely different theoretical angles. I may never know.

Categories: Financial Literacy, System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkHow Hard is It to Develop a Viable Algorithmic Trading System? (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on March 23, 2015 at 06:43 | Last modified: May 14, 2015 12:16Do you realize this has been a whirlwind exploration into advertising, marketing, epistemology, and scientific method?!

We started with Davey’s claim about 100-200 trading ideas being required to generate a tradable system.

Then we thoroughly analyzed the idea that strategies in the public domain will not be profitable.

We talked about the impact of the “big boy” institutions with all their funding, personnel, and technology (i.e. computing power, lightning-fast networks, high-frequency trading platforms).

We talked about the impact of good-sounding ideas and the limits of our ability to understand the actual veracity of such claims.

In the final analysis, I think reasonable doubt abounds with regard to many things covered in these last four posts. Yes, strategies in the public domain should be low-hanging fruit for the institutions who can easily develop them.

But we don’t know if this actually happens.

We don’t even know how many institutions are fully staffed with financial engineers, quants, and an overload of computing power.

We certainly don’t know how much capital these institutions control nor how much capital is sufficient to exhaust the profitability from a trading system.

So I say give it a whirl! If you have the wherewithal then start with something simple that you can find in a book or on-line. Optimize to understand the parameter space and get an idea if the strategy is capable of robust results or only fluke occurrence. Walk it forward to see how the out-of-sample results look. If it survives those steps then incubate it by paper trading to monitor it. Finally, start live trading in small size…

…all the while, continuing to develop other systems to compliment or replace when need be.

This is how business gets done.

Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkHow Hard is It to Develop a Viable Algorithmic Trading System? (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on March 20, 2015 at 06:46 | Last modified: May 14, 2015 11:40Good-sounding ideas may have persuasive impact when coming from sources perceived to be reputable.

If this is true then since some gurus say strategies in the public domain will not be effective, many retail traders will not even try to develop them. Paradoxically, the less attention a strategy gets, the more likely it is to work. The big institutions with all the funding, financial engineers, and computing equipment are less likely to be deterred by claims that “sound” good. Running trading strategies through the mill and live trading in large volume is what they do. They will cut to the chase to see if anything is really there.

The retail traders who are persuaded not to develop these public strategies may also be more prone to curve-fitting. If they believe it will take something more than simple public strategies to be profitable then they may try complex combinations of indicators in hopes of finding the Holy Grail.

This is all speculation, of course, and a digression at that…

Going back to the original forum post, I responded:

> At the risk of getting my nose chopped off,

> I’m going to voice an opinion here:

>

> I completely disagree based on semantics.

> The difference between a trading strategy

> and a trading system is money management.

> In reality, unless people are trading

> “small” they are trading systems. An

> infinite number of possible trading

> systems may be derived from any given

> trading strategy. Some may win with a

> trading strategy and others may lose with

> the same trading strategy based on

> differences in money management and

> personal/institutional tolerance.

In other words, given the many different subjective functions that will be used, the different combinations of data used to develop systems, etc., any given strategy may give rise to a large number of potential trading systems. Edge is not likely to be squashed out so quickly, then, because there aren’t an infinite number of big money players and it is the big money players who rule the markets.

Take these last three posts, shake them up, roll, and what do we have?

Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkHow Hard is It to Develop a Viable Algorithmic Trading System? (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on March 17, 2015 at 02:46 | Last modified: May 14, 2015 10:49I left off with the idea that trading strategies in the public domain will be quickly developed and traded by institutions until the Edge runs out.

While I think this sounds good, it is only speculation. As with so many claims about investing and trading, the only way to know for certain would be to develop a large number of trading systems in the public domain and to trade them live for a period of time. Only then would I have the data necessary to collate the returns, to analyze the results, and to use statistical testing in determining whether Edge exists and for how long Edge persists. This could take a lifetime of work and many millions of dollars in trading capital to test.

Not gonna happen! Therefore, I can never truly evaluate veracity of the claim.

In the world of trading and investing, I believe ideas that sound good do have persuasive impact because many traders lack critical thinking skills. For this reason, I think traders perceive the words of apparent authority figures and trading gurus to be meaningful and true when in fact they are little more than good advertising pitches and marketing claims.

As mentioned above, though, I also believe I cannot know this for sure. The only way to evaluate the latter claim would be to interview a large sample of traders to determine what it takes for them to believe “good-sounding ideas” and to determine how much critical evaluation is involved. Just the task of operationally defining much of this (e.g. what it takes to believe, what constitutes a good-sounding idea, a scale for critical evaluation) strikes me as an extremely complex task that may or may not even be possible to carry through.

In case you’re keeping score, we have here a claim that cannot be evaluated for reasons that themselves cannot be evaluated.

I resign for the night before I get too confused.

Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | Permalink