Prerequisites for Trading as a Business

Posted by Mark on October 16, 2017 at 07:14 | Last modified: August 8, 2017 12:57Trading as a business means generating consistent profits to cover all living expenses. Usually this is a full-time, independent pursuit. While I don’t think advanced degrees are necessary, I can think of three prerequisites for a trading start-up.

First, some degree of math proficiency is necessary for this level of money management mastery. Arithmetic is most applicable in order to calculate profit targets, stop-loss levels, performance, buy/sell points, position sizing, etc. A more advanced math background can make some derivative concepts more intuitive because option pricing models are based on differential equations. This isn’t mandatory, though; one can trade without having any knowledge of option greeks at all.

The second prerequisite for trading as a business is a strong capacity for critical thinking. No industry may be more littered with fraudulent pitches, false marketing/advertising claims, and overall chicanery than finance. I have written about this subject extensively (e.g. here, here, here, and here). In designing a business plan and sticking to it one must avoid being derailed into the quicksand. A background in statistics is a good defensive arrow to have in the quiver. Statistics provides a solid foundation from which to put questionable performance claims into reasonable perspective.

Critical thinking defends against the death knell that is being defrauded and suffering losses. Even greater than the financial losses may be the psychological damage in terms of trust, confidence, and safety: three key components to a fledgling business effort. I have spoken with a handful of people who have been violated by shady advisers. Once (if) they got out they never wanted (or couldn’t afford) to invest again (also reminiscent of catastrophic loss). I strongly suggest avoiding any black box system or advertisements of unrealistic returns. Steer clear of advisers who charge too much or smooth talkers who seem like they may have cut their teeth selling used cars. These last two sentences deserve separate blog posts of their own.

Finally, trading as a business requires money! Start-up capital is a safety cushion because like many other businesses, beginning traders often lose money (early success may actually be a curse leading to false confidence and a subsequent failure to adequately assess risk). Without this cushion, the stress of being forced to profit to stay afloat with bill payments can make long-term survival difficult. As the learning curve is scaled, magnitude of living expenses will dictate how large the trading account must be. A six-figure trading account might be necessary to cover the house, credit card, and insurance payments without taking on risk so great that Ruin is likely.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkManaging Winners (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on October 13, 2017 at 06:19 | Last modified: August 4, 2017 11:47Today I want to conclude my discussion on managing winners.

I can imagine something like the following if I were to start managing winners. Placing trades daily, I would see some days where number of open positions would decline precipitously. Over the next couple weeks I would build back toward a maximum number unless other positions had been managed in the interim. The big losers would be unaffected. Smaller losers would have a better chance at being flipped because they may at some point hit the profit target (think probability of touching). Management of winners (e.g. at 50% max potential profit) means the average win would be smaller.

Taken together, persistent big losers, higher win rate, significantly smaller average win, and equal number of trades all strikes me as a recipe for disaster.

One thing I observe in daily trading without managing winners is a mix of “in-play” and “out-of-play” positions. Recently placed trades are in-play with responsive position greeks. Older trades often carry unrealized gains approximating max potential profit. Even big market moves are unlikely to affect these older, “out-of-play” positions due to negligible, unresponsive deltas, gammas, and thetas. With the exception of MR, the total portfolio acts as if these out-of-play positions were already closed.

Reflecting on these observations makes me thankful the market hasn’t made any large, adverse moves as of late. Such moves tend to increase the number of positions in play up to 100% (managing losers—perhaps with a SL—can decrease total number). I am grateful for the trading experience that allows me to make and analyze these observations because at some point, volatility will return in a big way marking the return of stressful nights [hopefully not for very long]. My goal is to factor all this into the trading system development.

Reflecting on these observations also makes me think that carrying some out-of-play trades is part of the whole design (i.e. perpetual scaling and time diversification). I could close out-of-play positions to cut risk, though. Indeed, I strongly suggest other option traders “do the right thing” and adhere to such a guideline. In effect, closing out-of-play trades is managing winners albeit much less aggressively (e.g. 80%-90% max potential profit as opposed to 50%). The impact on performance metrics is therefore going to be different than that profiled in many of the TT studies.

I will wrap this up with an empirical question for the future. As a more conservative way to manage winners, exiting out-of-play positions may also be conceptualized as buying back-end insurance. How does this compare, I wonder, to buying the insurance up-front in the form of being net long [DOTM] contracts or buying a small number of NTM hedges?

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkManaging Winners (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on October 10, 2017 at 06:55 | Last modified: August 4, 2017 08:27One direction I may or may not choose to explore at some point is that of managing winners. I have trouble wrapping my brain around this concept and today I will explain why.

Managing winners is a frequently discussed concept by the Tasty Trade (TT) folks but it certainly is not a new idea. In the past this has been described as a “yield grab” or “profit target.” Just like I might manage losers with a stop-loss order, I can manage winners based on a variety of criteria.

The TT philosophy is to manage winners, adjust (or not) losing trades if tested, and trade small. If a trade goes to max loss then I don’t get hurt because my position size is small. Some trades get down significant percentages but then recover to win, which is why they don’t advocate managing losses.

One of the problems I have with this approach is doubt over whether I can “trade small” and still make enough to pay the monthly bills. I could certainly do this with a multi-million dollar trading account. Few retail traders have this luxury, though. I see this as a big problem for anyone looking to trade full-time as a business but it probably doesn’t affect TT viewers very much if my lack of success in finding other full-time traders is any indication. “Trading small” suits part-time/hobby traders who don’t rely on trading profits to cover living expenses.

According to TT “research” (I use that term loosely for reasons discussed here), managing winners increases win rate, number of trades, and profit per day while decreasing standard deviation of returns. They generally conduct studies by comparing trades held to expiration with trades closed at a profit target. In both cases, a new trade is placed after the old trade is closed.

I have tailored my backtesting methods to avoid the pitfall of insufficient sample size by entering new trades every trading day. At some point I realized that as a perpetual scaling technique, this might be a viable approach to live trading. As long as I keep my daily position size small, the total position size may remain reasonable. This has been at the core of my NP research.

I believe it is through this looking glass that I get confused when contemplating management of winners. Managing winners allows for more frequent trade placement but I am already placing trades every day as part of my scaling effort. My number of positions is, in other words, already maxed out. Opening multiple new trades on a favorable market day that sees a number of winners managed (e.g. a big up day for NPs) would compromise my time diversification, which is not something I will pursue.

I will continue this discussion next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkProfessional Performance (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on June 1, 2017 at 06:30 | Last modified: February 16, 2017 14:25Last time I discussed management of other people’s money. Today I want to focus on my recent trading performance.

On September 21, 2015, I began trading my personal account very similar to the way I would professionally manage money for others. I have traded every single day while adhering to a defined set of guidelines for opening trades. The little flexibility I have maintained with regard to position sizing and closing trades would be omitted as a professional money manager. Rather than using discretion, if someone wanted to squeeze out more return then I would discuss the possibility of a larger portfolio allocation to my services.

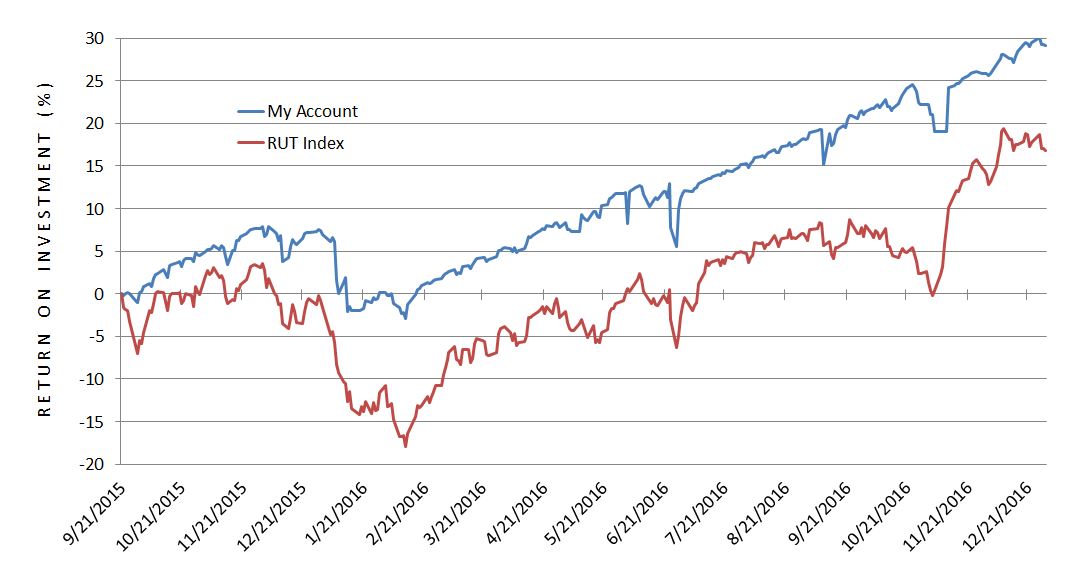

Here is a graph of net ROI from 9/21/15 through the end of 2016:

Over 15+ months, I have outperformed the index 29.2% to 16.8%.

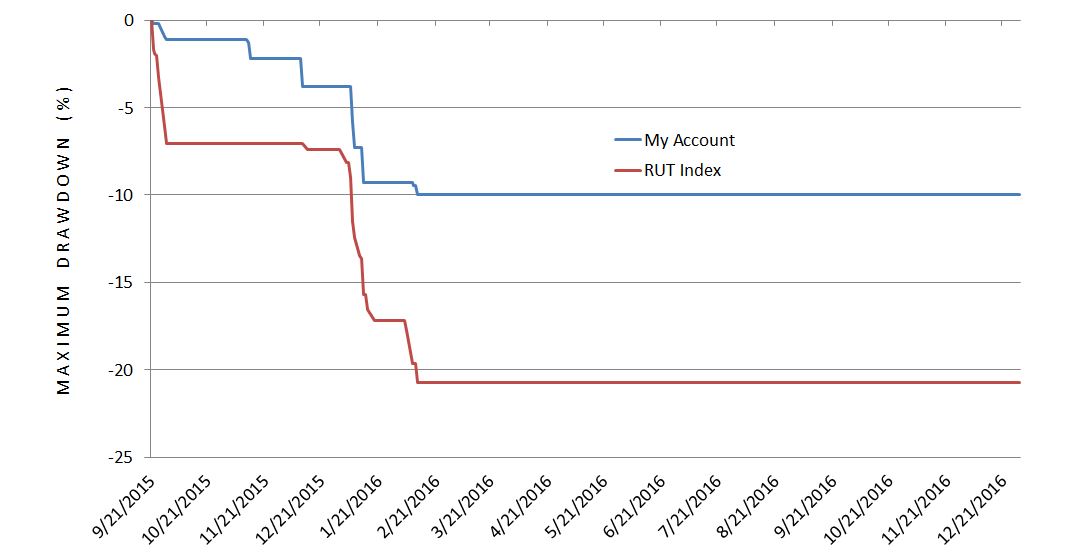

Here is a graph of maximum drawdown (DD):

In addition to a larger total return, my max DD was smaller than the index: -10.0% vs. -20.7%. February 2016 offered a moderate market pullback and my ability to keep DD in check resulted in a 3.6x better risk-adjusted return (ROI divided by max DD): 2.92 vs. 0.81.

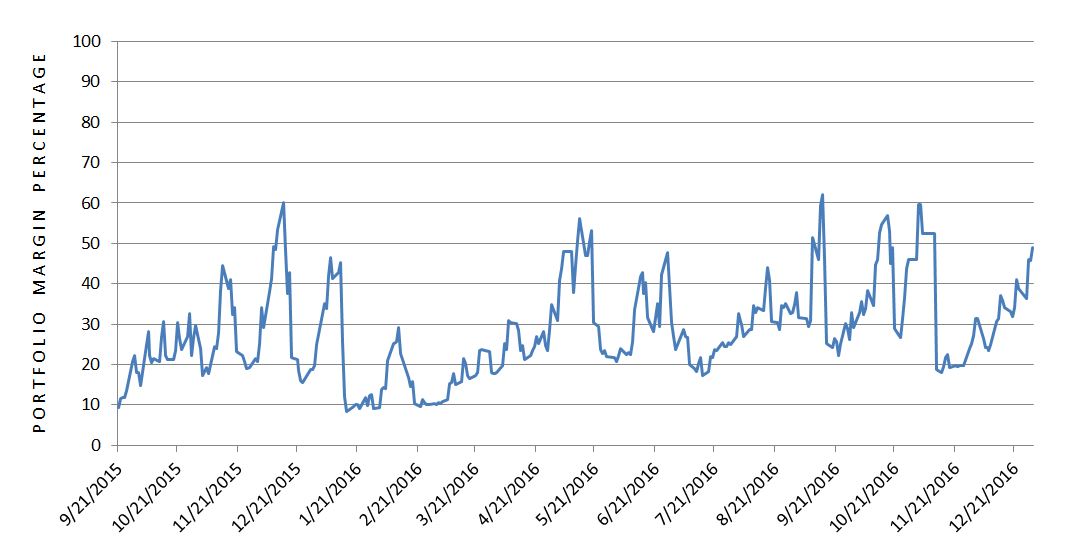

Because ROI and max DD are both a function of position size, I graphed daily portfolio margin requirement (PMR) as a percentage of account value:

PMR ranged from 8.27% to 62.2% with an average (mean) of 28.6% (standard deviation 11.9%).

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkProfessional Performance (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on May 30, 2017 at 06:52 | Last modified: February 16, 2017 11:20A couple months ago I did a long-awaited performance update. Today I want to focus on the last part of that record.

Over the last few years, I have contemplated the idea of trading for others. The main thing holding me back is doubt that others will find me credible. I consider myself an industry outsider (i.e. have never worked for a financial firm) and I don’t have an official track record.

One way to generate an official track record would be to create an incubator fund. My understanding is trading the incubator fund would be no different from what I currently do except that it would be audited by an expensive accountant. An accountant with a solid reputation may leave the performance record with more credibility.

Then I read posts like this and get really discouraged:

> Unfortunately with hedge funds, you cannot

> use any track record from a previous fund

> or personal trading (even if audited). So if

> you are a famous fund manager you will raise

> all you want off your reputation because

> everyone is aware of the returns you have

> generated in the past—returns that cannot

> be used to market the new fund. With regard

> to an audit, the minimum cost of a respected

> firm is $30K per year. It is supposedly

> expensive because of their liability. But it

> would be a waste of time anyway because

> institutions don’t pay attention to funds

> smaller than $40M. Even the funds of funds

> looking to invest in small time start-ups

> don’t even peek if you’re under $10M. So it’s

> completely on you to impress others enough

> to raise the initial millions and start building

> that track record. Start-ups with little capital

> face those headwinds of large audit/tax/legal

> expenses. If you don’t have “friends and family”

> willing to contribute based on their years of

> knowing you then your only hope is to

> outperform most other hedge funds out there,

> which is not easy to do.

Does this guy know what he’s talking about? I really don’t know but it does not sound encouraging.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (2) | PermalinkThe Risk of Going Naked (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on February 27, 2017 at 07:26 | Last modified: December 22, 2016 11:23I recently presented some excerpts from an online forum regarding the risk of trading naked options.

This is the kind of sobering talk that makes me uncomfortable with leverage. Regardless of the extent to which market turmoil occurred in the backtesting period, a severe enough market crash could always bring to fruition something worse.

Without leverage, drawdowns tend to be minimal, risk of Ruin is relatively small, and quality of sleep is restful throughout. While I am tempted to take advantage by boosting position size for better total return while maintaining equal or lesser drawdowns, doing so means adding leverage right back into the equation.

If I want to hedge myself against the most extreme moves then I can buy [cheap] insurance. This will increase return on capital. This will also save me if the catastrophic market crash actually takes place, which has anecdotally happened every 5-7 years throughout the current century. The market will more commonly fall several percentage points and level off or reverse higher. This magnitude of correction is nowhere near that required to realize max loss on the hedged naked puts (vertical spreads). The breakeven point would require an even larger drop since the insurance is not free.

And while that max loss is much lower than the “undefined risk” of naked puts, the loss is probably catastrophic either way. I’m tempted to backtest this and look at different position sizing but the sample size would be too small to allow for any meaningful conclusions.

I think it would be nice to insure the extremes and be able to claim “were the market ever to crash to zero, you would be covered [or even profit].” A total market crash is what doomsday forecasters love to prognosticate. Hedging against this is always possible with options but it comes at the cost of lower profitability during normal market action. My preferred solution is to allocate no more than X% of one’s total portfolio to this sort of “unlimited risk” trading.

Allowing for the possibility of catastrophic loss and managing risk by position sizing is, in my mind, what has relegated a strategy like this to accredited investors and hedge funds.

Then again, this argument could be easily contested. Common stocks—purchasable with leverage to investors who are not accredited—also go to zero (e.g. bankruptcy). While baskets of stocks rarely go to zero and indices have never gone to zero, all of the above have suffered catastrophic losses: pick any stock market crash. Limiting total portfolio allocation, therefore, is probably smart whether dealing with naked puts or long stock.

In the eyes of the regulators, naked puts would probably be okay for anyone as long as position sizing is based on Reg T margin requirements (i.e. cash-secured).

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkThe Risk of Going Naked (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on February 21, 2017 at 06:35 | Last modified: December 14, 2016 16:13Today I want to step back and review the risk of trading naked options.

The following exchange occurred in a Yahoo! Group I followed back in May 2015. R started it out:

> I think anyone selling options should read

> The Black Swan by Nassim Taleb to understand

> low probability, high impact events. This is

> the risk with leveraged naked option selling.

> To give an extreme example, nobody in their

> right mind plays Russian Roulette with a gun that

> has a barrel with 99 empty chambers and just

> one bullet. Even though you are “correct” 99% of

> the time, when you are wrong it’s game over.

V wrote:

> I was in no way doubting your numbers. I just

> wanted to know if you were writing closer or

> using more margin or different underlyings.

> I apologize for the misunderstanding.

V also wrote:

> It’s all good. I appreciate the openness of

> the group and the desire to educate and

> enlighten everyone. The returns are beating

> all hedge funds, which is amazing to me. I

> hope I didn’t come off as skeptical.

I responded:

> You should be skeptical, V. Recent posts by R

> about naked option selling raise an extremely

> good point and very scary possibility for those

> trying to make a living by doing this. The other

> side of the coin is that this work should not

> simply be dismissed because it’s naked option

> selling. There’s plenty of reason to think that

> it can work given particular management

> techniques and strategies: much of which are

> discussed in this group.

>

> Another reason to be skeptical is that even

> people who report solid returns are sometimes

> “under the influence.” They may never have

> seen significant downside and may be ignorant

> as to how positions are affected when volatility

> truly explodes. People might report returns

> accurately but, as R noted, if those returns are

> annualized and we have a 2 SD downmove a

> couple months later then those annualized

> returns will never be realized.

>

> Whenever people start talking or writing as if

> anything in trading is a sure thing or an ATM

> machine, I become suspicious. I believe that’s

> when you should start asking what they’re

> missing or where they are wrong. If you

> can’t find anything then maybe they are truly

> onto something.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkDeleveraging Put Verticals (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on October 27, 2016 at 05:27 | Last modified: September 29, 2016 10:34Last time I discussed the possibility of rolling out the put vertical if the market moves against me. Keeping with the theme of longer trades, I will now discuss trading less frequently as a way to deleverage.

Rather than deleveraging by holding a multiple of the margin requirement on the sidelines, I could be more selective in time and trade less often. I mentioned how 30% (or less) would be sufficient to meet my income goals rather than the lofty 120% annual returns promised by the vertical spread. I could, therefore, stay out of the market until the underlying prints a relative low. Alternatively I could use a momentum indicator like RSI and trade only when a critical value (e.g. 5, 10, 20) were crossed. By holding out for “higher-probability entries,” this is another way to deleverage since being out of the market represents lower risk exposure.

Backtesting can give me a historical sense of how often my trade criteria are triggered. How many times has the underlying printed an x-day low? How often has the RSI crossed above/below critical value y? If the number of occurrences is too low for my revenue requirements then I can lower x or raise y. I can lengthen/shorten the RSI period as another way to vary trade frequency.

More importantly, backtesting can help me understand whether my “high-probability signals” are actually higher probability. I have been suggesting placement of bullish trades after the market sells off but I have data suggesting the market may be most volatile in both directions when it is oversold. From a risk perspective, these may be precisely the times to stay out of the market altogether.

One final perspective on deleveraging regards staying ahead of the losses. For a $2.15 credit, 12 trades would generate $28.80 in profit. I then have no net risk until I hit a max loss because the profit I have generated is enough to cover that loss. Once I hit 24 trades then I have earned money to offset two max losses. This could be done in less than 10 months.

If I feel confident after enough “max loss units” of profit have accrued then I can increase contract size accordingly. At the larger position size, one max loss can wipe out significant gains but profits will also accumulate more quickly.

Profit hereby represents deleveraging because the net income is banked and able to offset future losses when they occur.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkDeleveraging Put Verticals (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on October 24, 2016 at 06:28 | Last modified: September 29, 2016 09:41Today I continue by discussing risk reduction of the put vertical strategy.

The primary factor that determines position sizing is probability of profit. Assuming I allocate full capital, this indicates how likely I am to survive until tomorrow. The lower my probability of profit, the smaller I will trade. I also want to understand average-loss-to-average-win ratio. If one loss wipes out many wins and I don’t have a sufficiently large probability of profit then I may not believe I could ever recover from a loss. This would be a strategy to avoid. I have talked about catastrophic loss and drawdown especially as it pertains to position sizing extensively in this blog.

The sample trade given has an annualized ROI of ~122%* but also hits max loss if the market falls >3.2% at expiration, which is not a rare occurrence. I do not need to profit at an annualized rate of 122%, though, to meet my profit goals.

One thing I could do is deleverage the trade by holding some multiple of the margin on the sidelines. The sample trade has a margin requirement of $64.05. If I allocate $64.05 * 4 = $256.20 instead then my annualized ROI falls to 122% / 4 = 30.5%. Not only is this sufficient for me, it allows for a positive size increase up to fourfold. If the market falls 3% then maybe I double the size and roll down. If the market continues to move against me then I could repeat. Backtesting can give an historical winning percentage for this trade, which can help me with initial position sizing.

Unfortunately, deleveraging does not result in a proportional increase in downside protection. I thought allocating 4x initial margin to the trade was effectively increasing my downside protection to 12.60% (3.15% * 4), which would be far less likely to occur in 10 days. As expiration approaches OTM options decay exponentially faster, which may impede my ability to roll down for enough credit to recoup losses even with a doubling/quadrupling of position size.

If the market moves against me then another possibility would be to roll the trade out in time. This would soften the blow from rapid option decay. I need to be careful, though, because in addition to lowering annualized ROI by deleveraging I would now be further lowering annualized ROI by lengthening trade duration. This decreases number of potential trades per year. Avoiding a loss is arguably the best thing I can do to save performance but I also want to monitor realistic probability the ROI will meet my income needs.

* Annualized indicates attainable by continuously having an open trade and winning every time, which is fictional at best.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkDeleveraging Put Verticals (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on October 19, 2016 at 05:46 | Last modified: September 27, 2016 07:00This post represents a meandering of thoughts about trading put verticals in reference to naked puts and position sizing.

As a starting point, consider selling a naked put on SPX on September 1, 2016. With the index at $2,166.20, I could sell one SepWk2 $2,125 put for $4.50. The Reg T margin on this would be $2,166.20 – $4.50 = $2,161.70. Were the option to expire worthless, the ROI would be ($4.50 / $2,161.70) * 100% = 0.21%. Since that option expires 10 days later, the annualized return would be ($4.50 / $2,161.70) * 100% * (365 / 10) = 7.60%. At expiration, the trade would be profitable down to $2,125 – $4.50 = $2,120.50, which represents [($2,166.20 – $2,120.50) / $2,166.20 * 100%] = 2.11% of downside protection. This means the trade loses money only if SPX has fallen more than 2.11% at expiration.

I believe it’s never a bad thing to make money when the underlying drops a little or remains unchanged.

On this particular trade, my maximum loss at expiration would be [($2,166.20 – $4.50) / $2,166.20 * 100%] = 99.79%. This is better than buying the underlying, which could conceivably lose 100%. I feel the real power in this trade is being able to repeat it 26 times (for example) per year in which case my maximum loss would be [($2,166.20 – ($4.50 * 26)) / $2,166.20 * 100%] = 94.6%. Over the course of 20 years I would look to work that cost basis down to zero, and, in effect, get my money back completely. But I digress…

One thing I could do to enhance the return would be to sell a put vertical spread rather than a naked put. This could be done with purchase of a long put at a strike price below the short put strike. Were I to buy a SepWk2 $2,100 put for $2.35, my net credit would be $4.50 – $2.35 = $2.15. My Reg T margin, however, would now be $2,166.20 – $2,100 – $2.15 = $64.05. My credit, therefore, would only be $2.15 / $4.50 * 100% = 47.8% of the original. My margin, though, would only be $64.05 / $2,161.70 * 100% = 2.96% of the original! My ROI would be $2.15 / $64.05 * 100% = 3.36%, which represents 3.36% * (365 / 10) = 122.52% annualized. That is bookoo bucks!

Before getting too excited, let’s get back to maximum loss considerations for the sobering reality. My maximum loss at expiration would be (100% – ROI) = 96.19%, which is better than the 99.79% were I to sell the naked put. My downside protection here would be [$2,166.20 – ($2,125 – $2.15)) / $2,166.20 * 100%] = 2.00%, which is a bit less than the naked put. If SPX were to drop to $2,100 or below at expiration then I would realize that maximum loss of 96.19%.

And therein lies the rub! With the naked put, SPX would have to drop 100% (to zero) to force me out at maximum loss. With the put vertical spread, SPX would only have to fall ($2,166.20 – $2,100) / $2,100 * 100% = 3.15% to force me out at maximum loss.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | Permalink