Covered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 37)

Posted by Mark on March 27, 2014 at 06:13 | Last modified: March 5, 2014 05:04I devoted the last four posts to discussion of the Martingale betting system because martingaling is to gambling what dollar cost averaging (DCA) is to investing/trading. Today I discuss incorporation of DCA to the CC/CSP trading plan.

The first step is to determine my maximum tolerance for loss. This is critical because I will approach that limit twice or four times as fast after doubling down once or twice, respectively. If I don’t know my maximum tolerance for loss–and most traders who have never experienced a volatile market and/or substantial loss do not–then the safest advice is probably to assume my tolerance will be small and to avoid doubling down altogether.

For the more experienced trader who is willing to commit additional capital, the next step is deciding when to DCA. The only recommendation MacDuff offers for this is “when a stock is on sale.” He seems to DCA inconsistently in his archives of successful positions.

Unfortunately, determining when a stock is “on sale” can only be done in retrospect. Any stock that went bankrupt was first down 10%, 50%, or more. Any of those levels could be considered “on sale.” Such identification might later be revised with the classification “falling knife” and dire regret had I acted and committed additional capital at the higher stock price. This is the risk of DCA and we can never get around it.

When to DCA is therefore an individual decision that must be made in accordance with your risk tolerance. Perhaps you will elect to DCA when the stock falls 30% or 50% or more. Perhaps you will do some backtesting [with a survivorship-free database] and decide what best fits your sample. I don’t have an answer to this question and I don’t think a correct answer exists. Period.

I will continue with more DCA discussion in my next post.

Categories: Money Management, Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkThe Tall Tale of Martingale (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on March 21, 2014 at 06:41 | Last modified: February 27, 2014 06:57Here’s a brief review of what I have discussed with regard to Martingale betting systems.

Although rare, extreme losing streaks most definitely occur. Martingale betting therefore favors shorter playing times because the longer I play, the more likely I am to encounter an extreme losing streak.

Martingale betting systems involve doubling my bet every time I lose. A long losing streak could easily have me down over $10,000 from a $5 initial bet.

Most people could never tolerate facing a loss that is orders of magnitude larger than the potential gain. If this has never happened to you then consider it extensively before attempting a trading system that carries a large potential drawdown.

I’ll go one step further…

If this has never happened to you then I strongly suggest assuming you would not be able to tolerate it either! Find another trading system or position size the system very small to prevent a heavy drawdown from significantly denting your total net worth. The alternative is learning something about yourself at the worst possible time: when you exit a trading system only to realize a catastrophic loss of capital.

Unfortunately, this has happened to me.

Would you ever stand being down over ten grand with the hopes of ending up five bucks? Most traders and investors cannot sleep at night or deal with the anguish of losing so much money when they stand to make so little even though they are one win away from vaporizing the entire loss.

Does that make us weak? Yes but no: with every additional loss, the huge loss I face doubles again! Maybe getting out with a few bucks to my name is better than losing absolutely everything.

In my next post I will describe a couple other ways casinos stack the deck against Martingale betting systems.

Categories: Money Management, Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 35)

Posted by Mark on March 7, 2014 at 06:06 | Last modified: February 20, 2014 05:54Before I continue the discussion of dollar cost averaging (DCA) as a position management technique, I want to present a disclaimer about my previous discussion of annualized return.

In general, the sooner CC/CSP positions go back to cash, the higher the annualized returns. Especially for positions that last less than one month, MacDuff notes:

> As always it is VERY important to realize that in order

> to actually achieve the calculated gains, one would need

> to successfully repeat similar transactions over the

> course of twelve months.

This particularly applies to weekly positions, which are becoming more popular with traders. A position that makes 1% in five days has generated an annualized return > 50%.

How can I realize this return on my whole portfolio?

First, since it is a 1-week position I must repeat the trade 52 times.

Second, if each position puts 1.5% of my portfolio at risk then I need to do about 66 of these trades at once.

At the very least, I’m looking at 52 * 66 = 3,432 trades per year.

That does not include positions that will have to be adjusted or manually closed, either. Unless I am willing and able to be sitting at my computer full-time during market hours, this is probably unrealistic.

What is more realistic might be to allocate a segment of my portfolio to weekly and “short-TERM” positions. I can recycle these frequently and book some supercharged returns in this segment while limiting trading frequency to something my time schedule and attention span can accommodate.

The bottom line here suggests I should continue to use annualized return as a guide to initiating and adjusting positions because this provides an apples-to-apples comparison regardless of position duration. I can be enthused about exceedingly high annualized returns–but not because I would ever expect to realize such a return on my whole portfolio. Rather, supercharged positions may serve to offset the periodic longer-term positions that will drag on for years.

The latter seems to be an unfortunate reality of CC/CSP trading just as “dogs” are an inevitable part of stock investing.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 34)

Posted by Mark on March 4, 2014 at 04:23 | Last modified: February 18, 2014 13:24Before I continue the discussion of dollar cost averaging (DCA) as a position management technique, I want to expound on a statement I made that gets at the core of CC/CSP trading.

Recall from my last post:

> DCA lowers the cost basis… over 28%, which leaves

> $6.48 less to recoup for position profitability. This

> can save months!

The goal of these positions is to have the short call be assigned (CC) or to have the short put expire (CSP). Once this occurs then the margin requirement is released and a new position may be initiated in its place.

Annualized return is about dividing total return by the number of years in trade. The shorter a position lasts, the smaller the denominator and the greater the annualized return.

Lowering the CB, which DCA allows us to do, decreases how much cash we need for breakeven or for position profitablity. Once profitable, I always want to keep an eye out for position exit via option expiration (CSP) or option assignment (CC). This effectively locks in my gain and allows me to move on.

The sooner I can end a position, the greater the annualized return. A core mantra of the CC/CSP approach is “back to cash, back to cash, back to cash!” In general, positions that take a few months or less can post juicy annualized returns (18-30%+) while positions that drag on for years score annualized returns in the single digits.

If single-digit annualized returns is the worst-case scenario then we’re looking at a trading approach with tremendous potential! Realize too that this will tend to occur when stock price tanks resulting in vast outperformance by the CC/CSP.

Unfortunately, I suspect the worst-case scenario is more likely to involve corporate bankruptcy, a relentless stock decline, or a sudden stock crash. If I only see this on 1 out of 1000 positions then I can comfortable absorb that loss. If I see this on 1 out of every 10 positions, however, then my optimism would suffer a substantial blow.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 33)

Posted by Mark on February 27, 2014 at 06:22 | Last modified: February 14, 2014 07:04Dollar cost averaging (DCA) is a CC/CSP position management technique I have alluded to in recent posts.

In Systematic Covered Writing, Rich MacDuff writes:

> The [DCA] strategy can be very advantageous

> when used with stocks that lose value… with a

> lower averaged cost basis, it will be easier to

> have the position go back to cash at a profit…

> [because] reaching a Continued trade status

> will occur at a lower strike price…

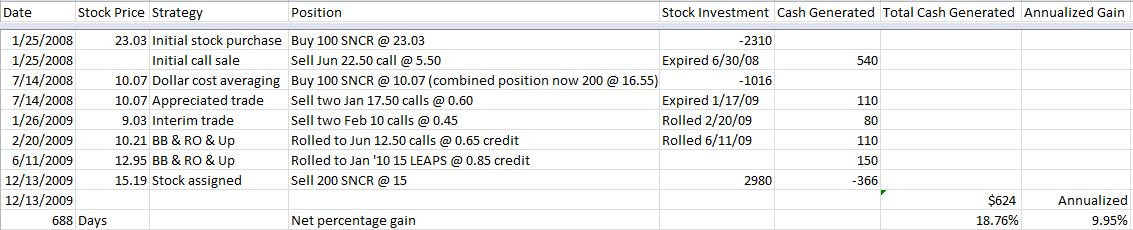

Here is a simplified example from the MacDuff archives:

In the first six months, SNCR fell ~56%. When a stock falls substantially, the short call strike will have to be lowered as little premium is available to sell regardless of expiration.

DCA lowers the cost basis (CB) over 28%, which leaves $6.48 less to recoup for position profitability. This can save months!

After DCA, “Appreciated trade” appears on 7/14/08 because the strike price exceeds the new position CB. Getting assigned at $17.50, in other words, would result in a profitable position. Note that in order to maintain a [$7.43] higher [than the stock] strike price, MacDuff sold an option six months out in time.

SNCR’s continual decline forces an “Interim trade” on 1/26/09 because the new strike price is less than the CB. Positions with interim trade status will result in loss if they end with assignment at the lowered strike. Because of this risk, interim trades involve selling short-dated options to allow less time for the stock to turn around and move strongly above the short strike.

Two BB & RO & Up adjustments were used to manage the bullish reversal in SNCR.

Finally on 6/11/09, the short call strike was raised to $15. While this is still less than the average stock price, it is greater than the position CB thanks to the series of credit trades. When SNCR was assigned at $15.00, this position made 18.76%.

Without the options, 100 shares posted a loss (from $23.03 to $15.19) and 100 shares posted a gain (from $10.07 to $15.19) resulting in an average return of 8.40%.

This would have drastically underperformed the CC position.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 32)

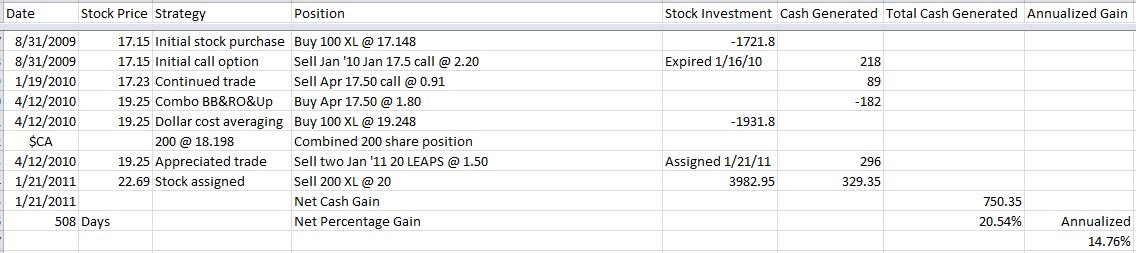

Posted by Mark on February 24, 2014 at 05:08 | Last modified: February 13, 2014 16:21Today I will analyze a Rich MacDuff example of the Combo BB & RO & Up position management strategy.

One thing I like to do is evaluate the CC/CSP performance against the stock. This position was held for 508 days and made 20.54%. The stock increased 32.30%. Since he bought more shares he would not have participated in the full gain. Half the shares would have made 32.30% and the other half 17.87% for an average of 25.09%.

While this is one occasion where I may not walk away with the warm fuzzy feeling of outperformance, consider some other things. First, the position made money at an annualized rate of 14.76%. I would be happy if my total portfolio returned that! Second, this would be one position among many during the course of a year. Some will return less and others will be supercharged. Ultimately, what I really want to know is how poorly the losers fare.

This position is interesting because it is not an instance I would have expected the Combo BB & RO & Up adjustment to be applied. The position was never losing money. Sans adjustment, the second option would have been assigned on 4/16/2010 for a gain of 17.83% vs. +14.99% for the stock. Why not simply take assignment and move onto the next position? If he wanted to stay with this stock then he could have initiated a new position at the higher stock price.

How valuable was the roll adjustment? Factoring in a $2/contract commission, I will calculate the annualized return of the roll:

(284 days – 4 days) / (365 days / 1 year) = 0.767 years.

The adjustment return is:

($1.75 – $0.34) / $17.148 = 8.16%

The annualized return is:

8.32% / 0.767 years = 10.64%

This is not great but acceptable–especially for a position he might be fighting to make/keep profitable. This one was profitable and handsomely so. The calculation helps me to better understand why the annualized return of the whole position was [marginally] subpar when the uptrending stock really posed little challenge at all.

My preference will be to reserve dollar cost averaging ($CA) for cases where I am forced to avoid a loss.

In the next post, I will talk more about the $CA adjustment.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 31)

Posted by Mark on February 21, 2014 at 04:44 | Last modified: February 12, 2014 06:57In the last post I described how to evaluate the value of potential adjustments. Today I begin discussion on another trade management technique called the Combo Buy Back and Roll Out and Up (Combo BB & RO & Up).

I previously made the points that trade adjustment is not risk-free and that we will encounter cases where a rolling adjustment cannot be found. In his book Systematic Covered Writing, Rich MacDuff describes this situation:

> Unfortunately, with an Interim Trade position there will be times

> when the SysCW Buy Back & RO & Up strategy will not work

> mathematically… the cash received for the Roll Out option would

> not be greater than the cash needed to close the existing option…

> there is a solution… the SysCW Combo BB&RO&Up strategy.

The steps for this adjustment are as follows:

1. Buy to close the existing short call.

2. Buy 100 additional shares of the underlying stock (this is dollar cost averaging or $CA).

3. Sell one more contract than was purchased in step 1 at a higher call strike than previous.

This adjustment should raise cash and increase the strike price.

MacDuff takes a shot at the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options, which is a booklet published by the CBOE that all new brokerage clients must be provided. The booklet states:

> The writer of a covered call forgoes the opportunity to benefit

> from an increase in the value of the underlying… above the

> option [strike] price, but continues to bear the risk of a decline

> in the value of the underlyling…

MacDuff argues this to be false. The Combo BB & RO & Up adjustment allows us to benefit from stock appreciation. We only surrender this opportunity if we do nothing.

Here is an abbreviated example of this adjustment from the MacDuff archives:

I will discuss this further in the next post.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 30)

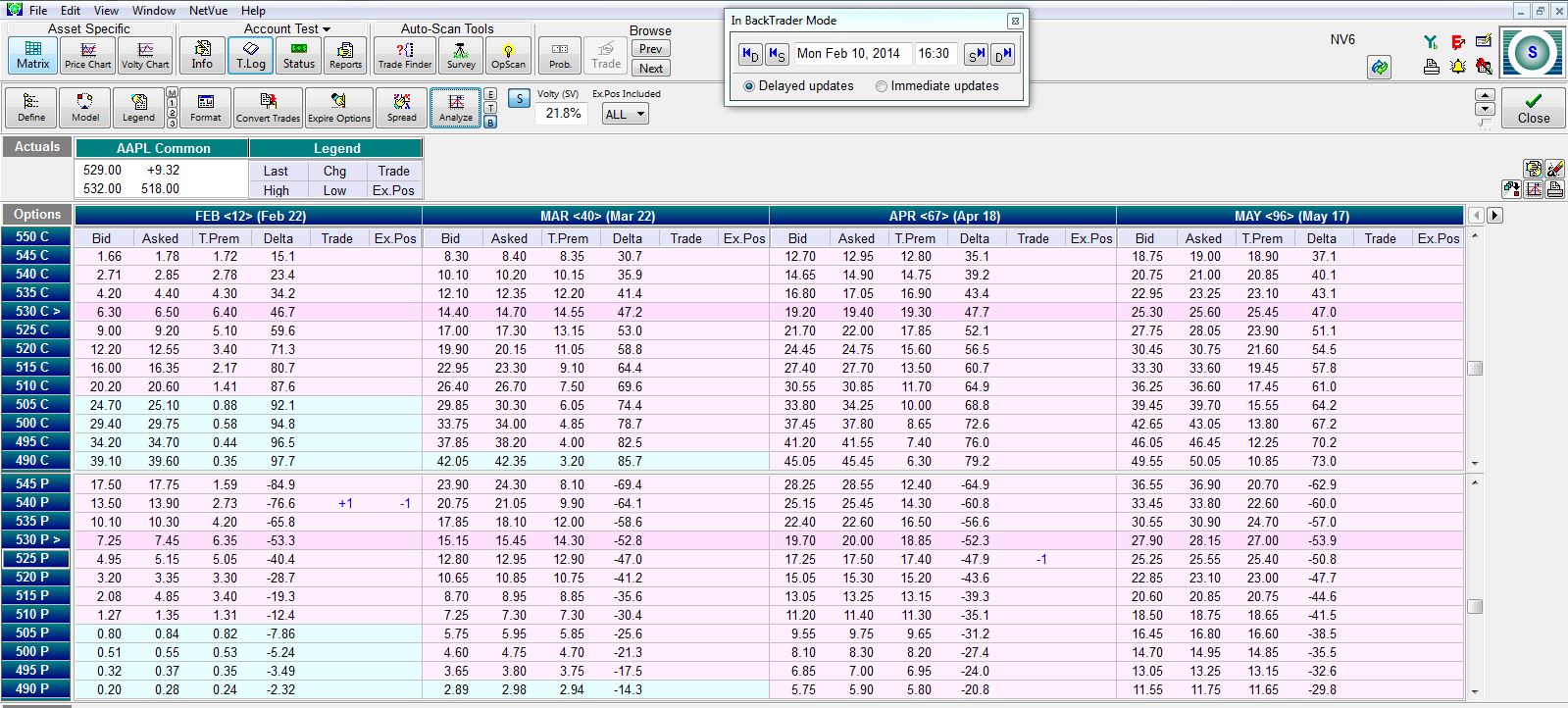

Posted by Mark on February 18, 2014 at 07:06 | Last modified: February 12, 2014 05:57The current discussion regards evaluating the value of a position adjustment.

Remember, the goal is to raise cash with every trade. Ideally, MacDuff would like us to raise cash at an annualized rate of 15% or more to ensure a profit of at least 15% annualized when the position is closed.

For a RO & Up short call adjustment, I take the net credit (debit) of the trade, add the decreased intrinsic value of the replacement option, divide by the cost basis, and divide by number of additional years sold. For example, suppose XYZ trades at $51.23, I have a short Feb(8) 50 call in place, and I can roll to the Jun(127) 55 call for a credit of $3.03. I have sold:

(127 days – 8 days) / (365 days / 1 year) = 0.326 years.

The adjustment return is:

($3.03 + $1.23) / $51.23 = 8.32%

The annualized return is:

8.32% / 0.326 years = 25.51%

That would be a valuable adjustment!

I can perform a similar calculation for a roll down and out put adjustment. For every point the stock price falls below the short put strike, I owe $1/share if assigned. If I can roll the CSP down then I basically take the decreased intrinsic value back into my pocket. This typically costs money, which I may be able to recoup by rolling the option out in time.

For example:

Here I am rolling out 67 – 12 = 55 days, which is 55 / 365 = 0.151 years.

The net credit on this trade is $17.25 – $13.90 = $3.35.

The decreased intrinsic value is $11.00, which makes the total return ($11.00 + $3.35) / $540 = 2.66%

Annualized return = 2.66% / 0.151 years = 17.64%

Once again, this is a valuable adjustment.

For Interim trades where short calls are rolled down, I can calculate the overall potential annualized return of the whole position to determine whether the adjustment is worthwhile.

For appreciated trades where short puts are rolled up, I can calculate the overall potential annualized return of the whole position to determine whether the adjustment is worthwhile.

A nasty situation occurs when the stock rallies sharply above a lowered short call strike (Interim trade) if the strike is below the current cost basis of the position. I will discuss this situation in the next post.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 29)

Posted by Mark on February 13, 2014 at 07:06 | Last modified: February 7, 2014 08:33Quick review: why bother calculating the annualized return of a RO & Up adjustment? Ideally, I want to raise cash with every trade. The initial trade should start with the potential to make at least 15% annualized. If each subsequent trade also makes at least 15% annualized then I will have an overall profit exceeding 15% annualized when the position closes.

Last time, the oft-mentioned theme of mirror image thinking got me out of a logical conundrum. I can, therefore, factor in the decrease of extrinsic value on a RO & Up when calculating the adjustment’s annualized return. What about with CSPs?

When a short put goes ITM, the profit is capped at expiration. Rolling down and out to lower the strike price therefore releases funds and makes them available. I should therefore be able to factor in the decrease of extrinsic value on this put adjustment when calculating the annualized return of the adjustment.

Issue resolved.

Evaluating whether to roll a short call down for a CC position or to roll a short put up for a CSP position is slightly different because the expiration month does not change. In this case I must calculate the annualized return for the whole position assuming it goes back to cash (i.e. call assigned or put expires) at expiration.

If rolling in the same month poses risk of being assigned at a disadvantageous strike price then my head needs to be on a swivel watching out for sharp changes in stock price and ongoing availability of replacement options for escape. If assignment at the adjusted strike price still results in a profitable position then it’s a choice with which I can feel comfortable.

In the next post, I will introduce the management technique of dollar cost averaging.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 28)

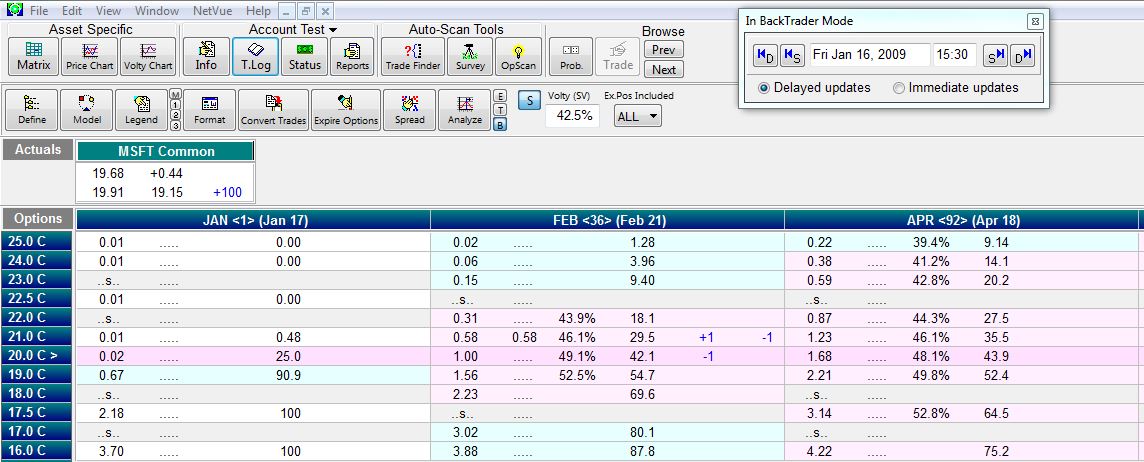

Posted by Mark on February 10, 2014 at 06:51 | Last modified: February 6, 2014 10:29Recall that MacDuff’s general philosophy is to raise cash with every trade. As my cash cushion continues to increase, eventually the stock will find a bottom and I will be able to exit the trade with a profit even if the stock has decreased over that time interval.

In the last post I showed a debit (i.e. cost money) adjustment and suggested the inclusion of the raised strike price when evaluating the adjustment. No I did not raise cash but raising the strike price to the stock’s current price essentially releases additional money, which is just as good as being paid.

I run into difficulty with this argument when considering a lowered strike price. A stock falling enough to require a lowered strike price (i.e. “rolling down”) to collect additional premium is what MacDuff terms an “Interim trade.” If I include the raised short call strike to the return calculation then would I also encounter instances where rolling down should factor in the lowered short strike to the calculation? If I did that then most Interim trades would be debit trades. For example:

This adjustment buys to close the short Feb(36) 21 call and sells to open a Feb(36) 20 call. The net credit is $0.42. By lowering the strike price $1, though, I have an obligation to sell the stock for $1 less if I get assigned. Yes I brought in $42 by rolling down but I cost myself $100. This is a debit adjustment; why would MacDuff allow it?

Something seems amiss with this comparison. With the RO & Up adjustment, I changed expiration months. The time I sold allowed me to calculate an annualized return. Here I did not sell time and the return therefore cannot be annualized.

I think the resolution has to do with the mirror image thinking I discussed earlier. The comparison should not be between RO & Up and rolling down. The comparison should be between RO & up for a call and rolling down and out for a put.

I will continue this discussion next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (2) | Permalink