Sub-Adviser- and TPAM-IA Relationships

Posted by Mark on February 15, 2018 at 06:22 | Last modified: November 9, 2017 08:18Last time I detailed two phone conversations I had with recruiters. Today I will continue on my brainstorming journey.

After speaking with EJ and LPL Financial last Halloween, I did some research on how to become a third-party asset manager (TPAM) and generation of a GIPS compliant track record. I will discuss the latter in a separate post.

TPAMs are sometimes a broker/dealer offering. In other words, if an investment adviser (IA) signs on with a broker/dealer then TPAMs may be available under a drop-down menu on the platform.

A fine line differentiates TPAMs from sub-advisers. A sub-adviser is hired by the IA to manage client portfolios. The sub-adviser manages assets in accordance with IA guidelines and objectives. In contrast, a TPAM is an external manager hired by the client to manage assets based on client investment objectives. In a sub-advisory relationship, the IA is responsible for the recommendation and selection of the manager. With a TPAM, the client enters into a separate and distinct contract that gives the client ultimate authority to retain or to fire. An IA may or may not recommend a particular TPAM.

The level of supervision (accountability) maintained in sub-adviser vs. TPAM relationships is noteworthy. Due diligence is the depth of investigation expected of a prudent IA to determine whether a financial arrangement makes sense. This falls under the IA’s fiduciary obligation to clients and is probably greater for a sub-adviser than a TPAM. According to one lawyer, most advisers use questionnaires, in-person and telephone meetings, and performance reports on a quarterly basis to make sure sub-advisers abide by IA guidelines and objectives. TPAMs may be reviewed on a semi-annual or annual basis with regard to performance, personnel, and overall client services.

Due diligence commonly includes manager expertise, assessment of fit between investment strategy and client suitability objectives, fee structure, disclosures, and regulatory status. The IA should also review compliance controls and specify how communication between manager and client will proceed to define expectations for all parties involved.

Sub-advisers and TPAMs are two concepts that help me to better understand XC’s hypothetical scenario where I might trade for one of their clients. In that case, I would be a TPAM rather than a sub-adviser, which is why he would not risk their reputation by explicitly recommending me. I’m sure this could change if he got to know more about me and my trading philosophy.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkBrainstorming My Niche (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on February 12, 2018 at 07:03 | Last modified: November 8, 2017 10:39It’s no secret that I am interested in managing wealth for others. The next few blog posts will review some interesting conversations I have recently had along with some related writings that could be pushing me in that direction.

On October 31, 2017, I called and spoke with a recruiter for Edward Jones (EJ). As an EJ financial adviser, my job would be to move clients into products managed centrally by their dedicated investment team. I would also do extensive financial planning (e.g. budgeting, retirement and estate planning, asset protection) for clients.

I never believed that I would be a good fit as an EJ adviser and this was quickly confirmed. First, EJ is “very conservative” and derivatives are therefore not used (I disagree with the claim that options are more risky). Second, I would only be permitted to continue managing my own account per EJ guidelines. Third, rather than concentrating on planning, which is where I believe financial advisers excel, I want to stick with my area of expertise: maximizing investment performance.

Although the phone conversation lasted only 10 minutes, he did give me some ideas for further consideration. He suggested I reach out to some independent advisers affiliated with Raymond James or LPL Financial with the following pitch: “my background is in trading options and I’m pretty good at it. Could we sit down and have breakfast/lunch to talk about what I do and what I’m looking for?” He suggested they might compensate me with a percentage (e.g. similar to this).

I ended the call thinking a niche just might exist for someone like me to trade for the big firms (LPL Financial is #1 in total revenue from 1996-2017 according to Financial Planning magazine). Eager to confirm, I immediately contacted an LPL recruiter who told me they outsource investing to third-party asset managers (TPAMs).

“What does it take to become a TPAM for LPL?”

“About $40,000 to get an AIM-R compliant track record,” he said with a chuckle.

His information was a bit dated; he was talking about Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS).

I ended the phone call somewhat shocked at the cost. $40K might be enough to start my own IA or launch a fund. Why would I want to undertake the expense to become GIPS compliant with no guarantee of business thereafter? It seemed like I might be headed toward another dead end.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkIncremental Value (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on January 22, 2018 at 07:18 | Last modified: November 15, 2017 07:35I’ve been discussing the incremental value I would provide to an investment adviser (IA) as a result of outperformance.

The numbers get more interesting if I am able to outperform by 3%. Last time I discussed the incremental value (in terms of the 0.8% management fee) were I to return 7% or 8% (11% or 12%) rather than 6% (10%). If I were able to return 9% or 13%, though, then my incremental value over 25 years would be $102K or $196K, respectively. While still apparently low, my average management fee has now increased to 0.11%.

At some level of outperformance, I feel the management fee should be increased. From the perspective of trading as a business, annual losses are anathema. In the event this accompanies improvement over the benchmark drawdown, I still feel payment should be postponed until a new highwater mark is established. The caveat, as mentioned in Part 1, is that only qualified investors* can be charged performance fees per SEC rules.

Whether clients pay performance fees is up to the IA but I feel it’s fair for me to be paid more as a trader. This goes back to my Part 2 mention of getting more than 50% of the incremental fees. Number and size (AUM) of client referrals may always be proportional to relative performance. Although hard to definitively measure, the value of this may be significant.

It has gone without saying that some benchmark for performance comparison would have to be agreed upon before any of this is finalized. I would also make a case for risk-adjusted returns. Clients who sleep easier at night will be happier than those who are more stressed and fearful. This can be measured by Sharpe [Sortino] Ratio or volatility of monthly returns. As discussed above, I strongly believe this has value albeit difficult to make tangible. One never knows when new referrals might be the direct result of a happier, stress-free clients. One also never knows when a more linear equity curve might directly result in the decision to remain invested during a market correction that would otherwise have sent them screaming for the exits to lock in large losses. These are two extremely valuable possibilities.

If I had 25 million-dollar clients then I would be earning $29K/$63K/$102K or $55K/$120K/$196K per year for relative outperformance beyond 6% or 10%, respectively. While I would not expect to manage $25M immediately upon hire, contemplating numbers like these makes a trading gig more enticing—especially if the IA can persuade me that more assets are available contingent upon solid performance.

What I’m talking about is doing exactly what I do now—executing a trading strategy in which I strongly believe—with 26 accounts rather than just my own and having a good chance of being paid [well] over $50K per year for my efforts.** I could probably get on board with something like this.

* Qualified investors have a net worth, excluding primary residence, of at least $1 million or an annual [spousal combined]

income of at least $200K [$300K].

** All calculations taken from “IA(R) fees and earnings (hypothetical) (10-12-17).”

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkIncremental Value (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on January 19, 2018 at 06:44 | Last modified: October 13, 2017 12:01Last time I presented some initial calculations to determine the incremental value I might provide to an investment adviser (IA) as a result of trading outperformance.

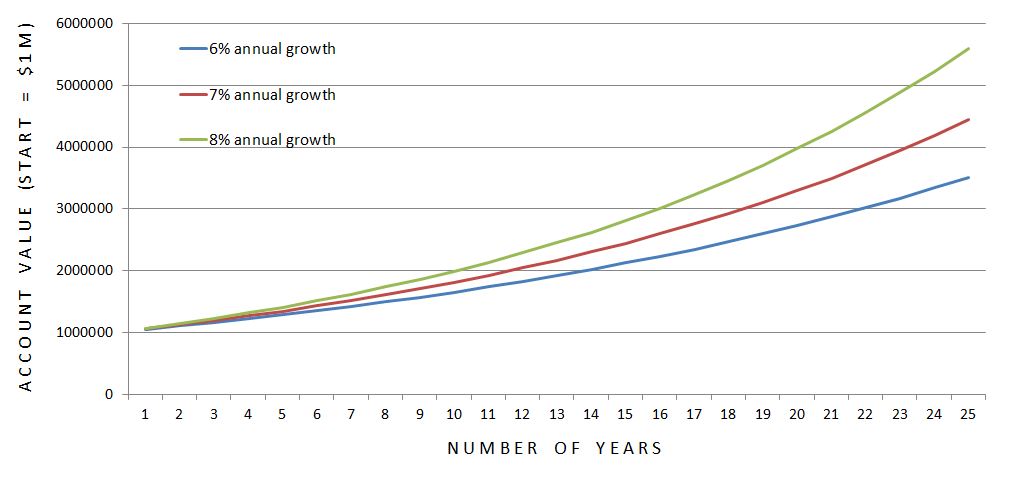

To isolate the impact of outperformance, I reran the analysis assuming 10% (rather than 6%) annual returns without me and 11% or 12% (rather than 7% or 8%) returns with me. Invested as previously described, $1M now becomes $8.86M, $11.11M, or $13.91M, respectively, over 25 years. The incremental value to the IA is now $110K or $240K for 11% or 12%. In splitting the difference I would earn $55K or $120K over that time.

Interestingly (to me), although outperformance is important, absolute performance plays a more significant role. Outperformance is identical on a gross basis in both simulations (1-2%). On a percentage basis, 7% or 8% vs. 6% is a 16% or 33% increase whereas 11% or 12% vs. 10% is a 10% or 20% increase. The significantly larger percentage increase is accompanied by a roughly equal ratio of incremental value share [($63K / $29K) = 2.18 ~ 2.17 = ($120K / $55K)] whereas the incremental value itself is almost double that for the 10%-12% versus the 6%-8% scenario.*

Note a similarity in calculated numbers for my share. I would earn $63K (over 25 years) by returning 8% instead of 6%; I would earn $55K by returning 11% instead of 10%. I would prefer a conservative estimate and project 2% outperformance over 11% returns. I can comfortably imagine annual returns of 11%, though. I will also do quite well when the overall market is moving moderately higher. While I will [profit but] underperform when the market is screaming higher, history has not presented many such episodes (e.g. second week of March 2009 onward and following the 2016 presidential election). I almost want to say that I can comfortably imagine 2% outperformance and 11% returns per year.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Time, as always, will tell.

I think outperformance would provide more value to an IA than higher absolute returns. It’s great if the IA makes 13% one year unless the benchmark returns 14%. One case where I think outperformance might not be good would be when the IA loses money for clients. Being down less than the benchmark is a marketable accomplishment, but clients may still be upset. Hopefully a conversation about the importance of minimizing drawdowns would correct their perception.

Next time I will talk more about my cut.

* If you are someone who spends modest time doing daily computation then you might be laughing at me just now for a failure to recognize basic arithmetic properties. Admittedly, I am a bit rusty with the mathematical proofs but believe you me, I still crunch numbers quite well!

Categories: Money Management | Comments (1) | PermalinkIncremental Value (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on January 16, 2018 at 07:54 | Last modified: October 13, 2017 11:42The time has arrived to break out the spreadsheets and start dissecting exactly how much I might earn as an investment adviser (IA) representative trading AUM.

I need to begin with some assumptions. Suppose the IA charges an annual management fee of 0.8%, which is assessed at the beginning of every year. As a conservative projection, let’s also assume the IA generates annual investment returns of 6%. A $1M account would therefore grow to $3.51M in 25 years.

Upon joining the IA, what if I were able to generate 7% or 8% per year?

Instead of $3.51M in 25 years, the account would now grow to $4.44M or $5.60M, respectively. That’s a significant boon for the client! This also brings incremental value to the IA in terms of management fees: an additional $58K or $126K, respectively, over 25 years. If I were to split that incremental value with the IA then I would make $29K or $63K with disproportionately more being earned as the years go by.

Keeping in mind that this trading gig must also be worthwhile to me, from a monetary standpoint I see some things not to like. First, my cut of the management fee ranges from 0.01% to 0.08% (or 0.14%). This seems minuscule. Second, that “incremental” detail is a killer. While I could make $29K or $63K over 25 years, if the client leaves the firm earlier then I will be effectively starting over with someone new. This feels like a mortgage where significant equity doesn’t start to build until later in the term. Although the incremental approach would keep me motivated to do well, I would rather be paid the average annual fee of 0.04% (or 0.07%). Besides, I don’t believe my history suggests a need for any additional motivation.

I could make a case for keeping all the incremental fees from my trading outperformance. The IA would benefit by earning more in fees as a result of my employment. My potential reward needs to be large enough for me to take on the challenge, though. If all the incremental fees went to me then it might represent a more acceptable wage (still small at an average of 0.08% or 0.14% over the 25 years) and a much happier client. That could lead to a larger book of business for the IA.

For now, in the spirit of keeping positive I think the bottom line is that I would make some money as a representative without having to do many of the back-office tasks required to launch my own IA. I wouldn’t have to file all the paperwork, come up with Form ADV, have legal work done, establish a new entity, hire a compliance team, deal with E/O insurance, cover all the overhead, or be forced to raise assets—the latter, especially, being no small feat.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkIncremental Value (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on January 11, 2018 at 06:38 | Last modified: October 13, 2017 11:50In contemplating transition from personal trading to wealth management as an investment advisor (IA) representative, I have struggled with fee structure. Thankfully the incremental value I bring to client accounts may buffer my cut as an intermediary.

What can I charge that is fair to the client and worthwhile to both myself and an IA that I represent?

In my opinion, “fair to the client” implies fees proportional to performance.* Consider this: if average annual hedge fund returns since 1970 are 12% while US equities have averaged 10% (approximations based on data from Bloomberg and Barclay Hedge) then does it make sense for the former to charge 2/20 (management/performance percentage fees) when the latter usually incurs a 1% management fee or less? I believe standard deviation is a second essential performance component and I would therefore be interested in comparing risk-adjusted returns. However, starting out with such a narrow edge in absolute return makes me skeptical that hedge funds will be able to justify a fee structure so extreme in comparison.

“Worthwhile to me” means my benefit must at least equal the cost. Working as an IA representative would require me to meet and speak with clients and with the IA, to be accountable to the IA, and perhaps to regularly commute to an office outside the home. These are big sacrifices to make especially when family is involved; much flexibility in my life would be lost. On the flip side, I would be associating [and hopefully collaborating] with co-workers and clients rather than operating in solitary confinement all day long. I would also be paid wages.

“Worthwhile to the IA” means the incremental value I provide is sufficient because a portion of IA revenue (management fee) would be redirected to me.

My initial thinking about the last two paragraphs was somewhat disappointing. I recently read about an IA charging 0.80% annually on the first $1M of assets under management. Thinking minimally, if I wanted to be paid anything more than 0.80% then the IA would be losing money to have me around!

Hope springs eternal when I consider the possibility of outperformance. Wouldn’t 11% annually be the same historical equity return mentioned above plus my 1% management fee or am I blinded by confirmation bias?

I will break out the spreadsheets next time.

* Per SEC rules, only qualified investors can be charged performance fees.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (1) | PermalinkStandard Deviation of Returns (Part 2)

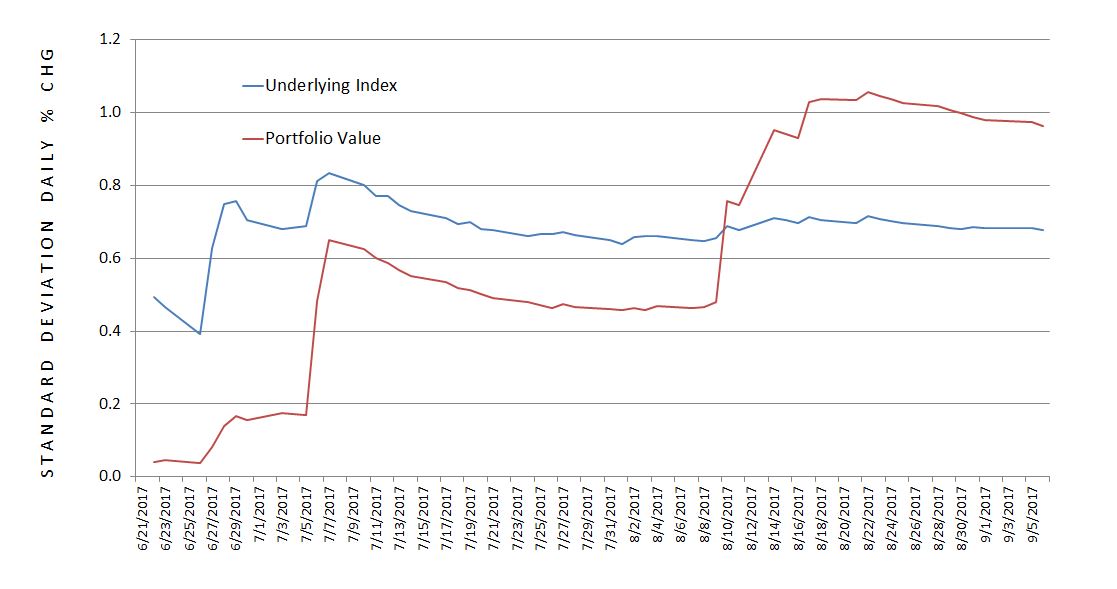

Posted by Mark on December 14, 2017 at 06:38 | Last modified: October 12, 2017 12:37I left off by illustrating how standard deviation (SD) of returns is greater for my new friends-and-family account than for the underlying index.

I think of naked puts (NP) as having a significantly lower SD of returns so this was puzzling. Is it a bona fide finding?

Applying the rolling-returns rationale, we can observe SD to be lower for NPs (red line) most of the time. When the market pulled back, SD moved higher for the NPs and has remained higher to date.

Max drawdown (MDD), also discussed in the previous post, would produce a similar result. MDD was roughly 4.8% and 6.6% for the NPs and underlying index, respectively. Despite the small sample size, this is a significant difference in favor of NPs.

I calculated risk-adjusted return (RAR) by dividing total return by SD of returns. This improved NP return from 6.41% to 6.66% and benchmark return from 0.12% to 0.17%. On a percentage basis this represents a much greater improvement for the benchmark but the magnitude of numbers is so disparate that the NP return is still far greater.

Weighing all the evidence, even if the finding is real it certainly may not be relevant.

But then I stumbled upon a solution.

The finding is real and a function of the leverage ratio. Leverage ratio is notional risk of the account divided by net liquidation value. It makes sense to say the more NP positions I hold, the wider account value swings I will see. The underlying index has no position size so its SD will remain constant. Studying SD of the daily account value changes is probably not very meaningful for this reason.

If I wanted to compare SD between NPs and the underlying index then looking at a large sample size of matched trades would probably be best. As one example, suppose I shorted a 700 put. The notional risk is 700 * $100/contract = $70,000. I would therefore use $70,000 as the initial account value and calculate the SD of daily % changes in account value until position close. For the underlying index, I would start out by purchasing a number of shares equal to $70,000 / index price. Daily index account value then equals number of shares multiplied by the index value on each day. From that I could calculate SD of the daily % changes. These two SDs could be compared.

So there you have it: leverage ratio is the culprit making my SD of returns larger than the benchmark! As long as the total returns are significantly better, though, I don’t expect much client pushback.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkStandard Deviation of Returns (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on December 11, 2017 at 07:12 | Last modified: September 10, 2017 15:03I have recently begun to trade a small friends-and-family account. In running the early numbers, I was surprised to see standard deviation (SD) of returns tracking higher for the portfolio than for the benchmark.

Based on my trading/research experience, naked puts (NP) generate comparable returns to the benchmark with a significantly lower SD of returns.

The best analysis I have between long shares and NPs may be the second graph shown here. In that analysis I did not calculate the total but using my naked eye and this online calculator, the NP portfolio returns 8.69% per year vs. 11.17% per year for the benchmark. That is not “comparable” returns—it’s a smackdown by the benchmark.

The graph does show this return comparison to be date sensitive. Just three months earlier (1.65% of the entire backtesting horizon), the NPs had a higher ROI than long shares. Across the whole graph, the NP line (red) beats long shares (blue) ~2/3 of the time. Statistically speaking, I worry about this inconsistency. Perhaps a rolling analysis should be done to get a larger sample size than just a single-point comparison, which may not be representative.

In the previous study I used maximum drawdown (MDD)—not SD of returns—as a measure of risk. When I looked at risk-adjusted return (RAR), the NP portfolio significantly outperformed despite the smackdown mentioned above.

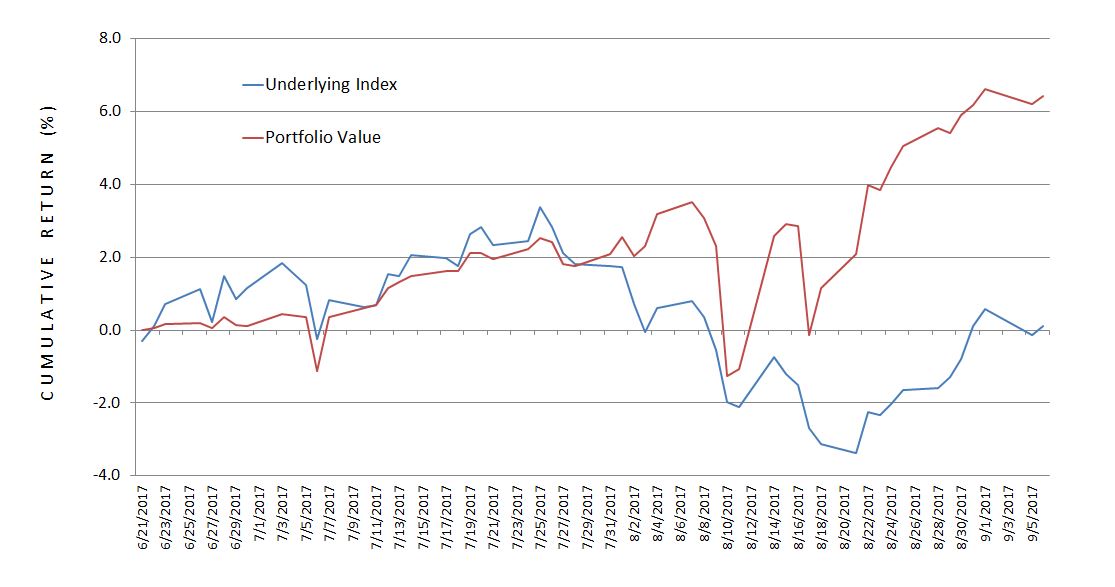

Now let’s move forward and study the NP portfolio I have been trading for 1/6 year. I track the cumulative return for the portfolio and for the underlying index:

This is consistent with what I have come to expect from NPs. The equity curves are similarly shaped. The underlying index or NPs can outperform when the market is higher or lower, respectively.

I calculate daily % returns so I can monitor the SD of both:

The NP portfolio shows a larger SD of returns than the benchmark! How can that be?

Categories: Money Management | Comments (1) | PermalinkWatching Out for Risk

Posted by Mark on May 10, 2016 at 06:46 | Last modified: March 28, 2016 09:16Many of my blog posts are inspired by forum discussions I have with other traders because thoughts had by others are often thoughts I once had too. Today’s example is about risk.

Over a year ago I was compelled to respond to “Pete,” a guy who had some definitive, optimistic words for trading strategies he claimed to be using. He posted a number of times before I responded with the following:

> If there’s potential reward then there is no such thing

> as zero risk.

>

> Your posts have full of phrases like:

>

> –“consistent weekly profits”

> –“‘gravy’ forever into the next generation”

> –“the coast is clear to keep it and make premiums

> until it runs up again”

> –“those who stayed are rich and retiring”

> –“sounds to me like profit all day long and all

> the way to the bank”

> –“this is a triple grand slam with insurance.”

>

> Where’s the one about trading being like an ATM

> machine that continuously spits out cash?

>

> Nothing about trading or investing is free, nothing

> is guaranteed, and nothing here is ever worth the

> kind of exuberance you seem to project with your

> posts. There’s risk inherent with everything and

> if you trade too large aiming to be too greedy then

> you will one day learn the hard way by getting

> blown out of the game for good.

Pete responded by asking me what I felt could possibly be wrong with some of the trades he was putting on. I replied:

> I’m not going to specifically analyze the pros/cons

> of your trade because we have other wonderful

> traders here who routinely share such insights

> Hopefully they can help with some of your analysis.

>

> Based on my real-world trading experience, though,

> focus on what I said in my last post. It’s at

> least urban legend (if not definitive truth: nobody

> knows) that over 80% of all traders lose money.

> Personally, I think the #1 culprit is unrealistic

> expectations. If you enter the markets thinking

> you’re going to make too much per month then

> you’re going to get beheaded. Your phrases that I

> quoted all suggest just that.

>

> Hence my caution: learn how to determine the real

> risk, watch your back, and be careful. If you don’t

> see the risk then walk (or run) far away.

I think this is good advice for everybody and that includes, first and foremost, myself. I try to remember this stuff each and every day.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkCatastrophic Loss (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on September 22, 2015 at 07:30 | Last modified: October 22, 2015 07:37In Part 2, I gave some background about what led to my latest catastrophic loss.

One thing I find tricky about the trading business is that catastrophic loss often looks foolish in retrospect. When I contemplate what happened to me in August, it seems absolutely absurd! Hindsight is always 20/20, though. More often than not, I’ve found sharing these stories with other people to be met with a lot of head nodding. We’ve all been there and many stories are commonly held.

One thing that makes my catastrophic losses difficult to stomach is the fact that I trade in a discretionary manner. With a systematic trading approach, I can see exactly where the profit and loss falls with regard to numerous other copycat trades. Discretionary trading means every trade is different and I have no context. Making things worse for this particular case is the fact that I’m quite sure the current drawdown would have been much lower with a more systematic trading approach. In this pursuit that is already boring at times, discretionary trading does help keep me engaged. However, when that means constantly battling the market and becoming emotionally drained, I can end up more vulnerable to catastrophic loss should a true market challenge present. Case in point: August 2015.

The emotional impact of catastrophic loss can be devastating. In the past, I have felt depressed and unwilling to get out of bed in the morning. I have felt like a failure and seriously considered going back to work as a pharmacist (e.g. “throwing the baby out with the bathwater”). I’ve felt gun-shy and very fearful about getting back into the market. I know one other guy who trades full-time. I heard from him a few weeks ago and asked how he managed the correction.

“I took a huge hit,” he said in his message. “I’m going back to work a real job.”

Talk about catastrophic loss and devastation! I was shocked and despite repeated calls, I haven’t heard back from him since. I’m not at all surprised he hasn’t wanted to face it and share his story. Most people don’t.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (2) | Permalink