Where Do I Start?

Posted by Mark on July 19, 2016 at 05:16 | Last modified: May 25, 2016 10:30The following question was posted in an investment group I follow:

> I was hoping someone might be kind enough to meet with

> me for dinner or drinks and show me the basics. I’m

> looking to get started investing but I have no idea where

> to start so it would be really great to get some advice.

Anyone who knows me would not be surprised to see me jump at the opportunity to talk about investing WHILE BEING TREATED TO DINNER AND DRINKS. Are you kidding me? I could talk about this stuff all day long for free and enjoy it. Dinner and drinks is just “icing” (figuratively, of course, since dessert does not seem to be included).

But then I got to thinking: what exactly is she asking for and does the question even make sense?

I know one thing: regardless of the teaching, any pupil may or may not make money in the markets. This theme runs extensively through my writings. In a recent post, for example, I quoted Garrett Baldwin who basically said consistent and accurate forecasting of future prices does not exist. For the same reason, nobody can guarantee profits.

This leads me to believe that education may be the only guarantee anyone can make in this space. I can teach her about stocks and investment vehicles: what they are, what it means to trade them, and how to trade them. I can teach her how to do the math to determine whether she is profitable. None of this guarantees she will make money, though: a singular fact that should be part of any introductory education.

For this reason, clarifying her question might be helpful. If she is looking for hints about my Holy Grail trading system or hoping to get me to spill my secret altogether over one too many beers then she will be disappointed. I think many people believe the Holy Grail does exist and finding it is just a matter of getting the proper education. If only it were that easy…

This is certainly not to say that education has no value. Some people search endlessly for the Holy Grail. They attend a plethora of investment seminars, buy “education” packages, and subscribe to black box trading systems. These are the people who never got the memo about the nonexistent Holy Grail and for them, this one lesson alone could have saved countless sums of time and money.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkForecasting and Accountability

Posted by Mark on June 6, 2016 at 07:15 | Last modified: April 26, 2016 09:45From an article in the April 2016 Modern Trader magazine on oil price forecasting, Garrett Baldwin wrote:

> At the heart of it is the incapability of the human mind to wrap itself

> around the sheer size and factors that go into this global market. When

> something is this large with this many moving parts, we try valiantly to

> find shortcuts or justify one specific variable. Each day, a headline

> says that oil prices fell because of whatever factor an energy journalist

> can point to that day.

>

> It’s over-simplification at best, and malpractice at worst… And it’s

> clear that no one has a clue what oil prices will hit by the end of the

> year because of so many factors beyond our grasp. No one is suggesting

> that forecasting should be abolished, but history has shown that when

> it comes to accurately predicting oil prices, all bets are off. Are we

> willing to admit we’re just not good at this?

> …

> Right now, oil prices are hovering below $30 per barrel, a level that

> was deemed impossible just a few years ago. I remember sitting in a

> lecture with a prominent economics professor not long ago. He told

> the room that we wouldn’t see oil under $100 per barrel in our

> lifetime again. He somehow still has tenure.

>

> In the end, I still argue the real problem is that there is no

> accountability. People are allowed to make any prediction they want,

> and it is quickly lost in the 24-hour news cycle. When the prediction

> doesn’t come true, the blame falls on some unforeseen variable.

The article was on oil prices but it certainly is good information to know about financial forecasting in general. Baldwin’s words are consistent with those of Bob Veras in Doomsday Forecasting (a Primer): “nobody, including those who reported your alarmist views, will check up on your track record.” The lack of accountability allows anyone to forecast anything.

Personally, I believe the fault should not fall on the forecasters but rather on the readers who try to make use of the information. Forecasting is not actionable, period. That is why I categorized this post under “financial literacy.” Once I can identify content as a forecast, I can dismiss it and move on.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (1) | PermalinkDay Trader Meetup Review (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on April 29, 2016 at 06:36 | Last modified: March 4, 2016 11:48Last time I praised the organizer of this new Meetup for being a humble, normal guy. Despite his best intentions, we were not spared from blind ego supplied by someone else in attendance.

Like Mr. Know-It-All and our friend DY, let me introduce you to WM. Before the meeting, he posted on the website, “Everyone should check out J M Hurst. He discovered how the market works by using electrical engineering math.”

The Meetup started with the organizer having everyone introduce themselves. WM began by taking 5-10 minutes to explain how Hurst has figured out the markets with his engineering math. He said this works for all markets including stocks, commodities, futures, and currencies: “if you analyze the data then you will see for yourself!”

Since my turn was next, I looked WM squarely in the eye and said “I tend to be skeptical so we will probably do some arguing later on.”

For 30 minutes out of the two hours, we did just that. I started by asking WM whether he is making good money with Hurst’s methods. He said no. I asked if WM’s level of sophistication is sufficient to understand the complex math behind Hurst’s methods. He said no. I asked if WM could reliably predict the future price move on some random charts by applying Hurst’s methods. He hemmed and hawed then failed at several attempts.

WM tried to defend himself by saying “I don’t understand Hurst’s teachings but I have no doubt that a group of us can combine our efforts and make great money.” My blood was boiling and I couldn’t help but raise my voice in talking to him because I felt he wasted so much of our time.

WM reminded me of entrepreneurs appearing on “Shark Tank” with outrageous valuations for their pre-revenue companies. Revenue is proof the product can sell. Without revenue there is little value. Unless WM had been successful making money the Hurst way, we have no reason to think anyone can. Why is he trying to sell it as the Holy Grail? How would he know?!

I am a fool destined for the poorhouse if I have blind faith in matters related to trading and investing.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (1) | PermalinkAccuracy of the Expected Move (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on April 21, 2016 at 06:54 | Last modified: March 31, 2016 05:19I previously reprinted a post from a trading forum along with my response from last year.

The original poster says the ATM straddle is a poor estimate for the Expected Move. What irked me was that he provided no data to support this claim. Had he done a large number of trades? Had he studied it? In case he did, I asked in my response who had done the backtesting on it. He did not respond.

Tasty Trade offers a specific definition of Expected Move: 85% of the value of the front month at-the-money (ATM) straddle OR the arithmetic mean of ATM straddle and the nearest OTM strangle. How do they know that is what people expect, though? They really don’t and they really can’t. It’s not like they surveyed a large sample of people to find out what size move is expected.

A deeper understanding of options does offer some association between the name and the definition. The straddle/strangle will profit on a move in either direction greater than its original price. If traders, in general, think the move will be larger (smaller) than the cost of the straddle/strangle then they will buy (sell) it. The net result of these supply/demand pressures will be the price. Theoretically speaking, then, one could say it reflects what size move traders are expecting.

In the past, I heard more discussion about “implied move.” I have no reservations about the word implied. “Expected” is potentially a misnomer because it connotes some intelligence is explicitly regarding this as likely to happen. We don’t know why traders are buying or selling those options, though, or how many of them even have anything to do with the straddle/strangle itself: they may be components of different positions.

Going back to the top, whether the Expected Move has any predictive value is a completely different question that lends itself to backtesting. Tasty Trade has since done some backtesting to suggest the actual move is usually smaller than Expected. This would be an instance of “herd instinct” and why it might pay to be contrarian.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (1) | PermalinkAccuracy of the Expected Move (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on April 18, 2016 at 07:19 | Last modified: March 23, 2016 08:51Last year, the following post appeared in a trading forum I follow:

> Using ATM straddles to estimate expected moves is

> very inaccurate, to say the least. I remember seeing

> this in some “beginner’s tips and shortcuts”

> resources years ago.

>

> For those interested in a more accurate, but still a

> quick-and-dirty estimation:

> https://www.tastytrade.com/tt/learn/expected-move

>

> You could always go more advanced and use a tool

> like Hoadley’s and GARCH(1,1) model. Or just use TOS

> IV numbers and Analyze tab to keep it simple.

I responded with the following:

> I don’t mean to sound critical but I think you

> bring up a couple good points worthy of

> discussion.

>

> Who knows how good either ATM straddles or

> any other formula is to estimate expected moves?

> In other words, who has done the research to

> study it?

>

> I’m guessing there are traders who have

> backtested this. I am not aware of backtesting

> data targeted for the public domain before

> Tasty Trade (TT). TT studies actual vs.

> expected moves all the time. I’m not sure if

> they’ve looked at ATM straddles vs. any other

> approach (like average of ATM straddle and one

> strike OTM strangle), though.

>

> A separate question from what is a good estimate

> is what is the expected move? The answer to

> this is whatever “most people” (or the “loudest

> talking heads”) regard as the expected move.

> In most cases, I think this is terminology that

> many people throw around casually without

> precisely defining. In most cases too, I think

> most people hear the term and think they

> understand even though they probably don’t

> because the definitions aren’t given.

>

> There’s a lot of crap in the Financial

> [trading/education] space that is neither

> actionable nor reliable. I believe we’re

> even bombarded with such information in

> this forum. That’s not to say forums like this

> aren’t worth reading though. Between the

> cracks, people do offer up some really good

> ideas every now and then.

I will conclude next time with a bit more commentary on this subject.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (1) | PermalinkState of Mind (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on March 14, 2016 at 07:31 | Last modified: February 6, 2016 10:50I could definitely use a research team with whom to work. Aside from cash, do I have anything to offer them in return?

I could never pay someone to do research for me. I don’t feel I’m at the point where I can hire employees and even if I had some, I don’t know the payoff would justify the cost. Besides, it would be hard to pay someone to do backtesting for me. I might hire a statistical guru to help me analyze results but that is something different altogether.

In exchange for helping me with research, I could teach fundamentals of trading but never a guaranteed system or strategy. I don’t believe I have such a guaranteed trading system, for one. Also, as I have been discussing, I don’t think it makes sense to teach or sell someone a discretionary trading strategy since it will fail at some point if it hasn’t already. I would say the same thing about a systematic trading system because I believe those break too.

How little it seems I have to show for working so hard over the last eight years to master this craft!?

Probably more than anything else, I feel I know a lot about what I don’t know, which I believe is requisite for success. I hardly believe I am the only person who got into trading with belief in the hype of making 6% or more per month. I think aiming for returns like that would cause me to go bust pretty quick.

Maybe this is simply an affirmation of the old maxim “if it seems too good to be true then it probably is.” The slippery slope is how we define “too good.” That’s one place I might be able to help.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkOn Discretionary Trading (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on March 8, 2016 at 06:49 | Last modified: February 2, 2016 06:55A recent option trading Meetup frustrated me immensely because of discretionary trading and the Lemming Effect.

I wrote about this group previously and described the source of my frustration named DY. According to another member, DY “loves to hear himself talk.” He says “I have nobody else to talk options with.” He doesn’t talk options with us either—he lectures. The last Meetup featured a financial adviser presenting on covered call investing. DY eventually took over the show by telling us that he:

- was approached by a publisher to write a book on options

- trades options on NFLX simply because he has already made so much money on it

- does 15-20 trades per week

DY then started talking about his short-term weekly trades. The organizer fell prey to the Lemming Effect and redirected her attention. Over the next 10 minutes, she asked DY a series of questions about his trading strategy and how he does it.

I think most discretionary traders are profitable for a variable amount of time [until they aren’t] and they usually represent as if they “get it.” Outsiders perceive them as experts and try to learn the discretionary trading approach. In most cases, I believe the strategy will eventually fail and leave the lemmings locked out on the cold doorstep.

I can either work to emulate another trading approach or I can work to learn about trading system development and develop my own system. If I do the latter then I can at least see what’s coming, have context for what to expect, and make tweaks when needed. If I copy someone else then I have no context and maybe only their claims about historical performance. When it stops working I am lost since my “teacher” may be gone or have moved onto something else entirely.

Regardless of how any individual trades and what validation steps have [not] gone into developing that approach, I believe people should first learn about option theory and fundamentals. After that, people should understand the philosophy and steps behind trading system development. This involves education about critical thinking and statistical analysis.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkAn Argument for Statistics (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on December 21, 2015 at 07:09 | Last modified: December 7, 2015 14:43In my opinion, trading system development is similar in importance to hypothesis testing and inferential statistics in addition to being something most traders don’t know much about.

Aside from my familiarity with statistics, I am a student of trading system development. Trading system development looks at measures related to profitability, consistency, drawdowns, and much more.

While I find this all interesting and potentially very useful, at the outset maybe I just want to know if my system is better than trading at random. Maybe I just want to know if my system is better than zero profitability. These are questions that lend themselves to inferential statistics because the null hypothesis would say “the system is not profitable.”

In the final analysis, I think we have at least two different approaches to trade validation. One approach involves hypothesis testing and inferential statistics. Aside from those with research backgrounds of some sort, I’m not sure who might think to employ statistics for this purpose. I think trading system development is more popular among algorithmic traders and those employed in finance since it uses parameters and jargon created specifically for the industry.

Perhaps the two are accomplishing the same thing but from completely different theoretical angles. I may never know.

Categories: Financial Literacy, System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkAn Argument for Statistics (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on December 18, 2015 at 06:16 | Last modified: March 31, 2016 06:27I left off with a general description of the statistical hypothesis testing process.

Once the assumptions behind a sample or experimental design are identified, the next step is to choose an appropriate statistical test to run on the data.

Select a level of significance (greek letter alpha: α), which is a probability threshold below which the null hypothesis will be rejected. Common values used are 0.05 or 0.01. By definition, status quo is likely to maintain. α states “if the chance of the sample being status quo is less than one in 20 (or 100, respectively), then I believe it is not status quo (i.e. reject H0) but rather something different (i.e. accept HA).”

Perform the statistical test, which will output a p-value. The p-value gives the probability of the groups being from the same population (e.g. no difference, or H0 is true). If the p-value < α then reject H0 and accept HA.

Hypothesis testing is not perfect. A type I error occurs by rejecting H0 when H0 is in fact true. This is also known as a “false positive” and the probability of making this mistake is equal to α. On the flip side, a type II error occurs by not rejecting H0 when H0 is in fact false. This is a “false negative.”

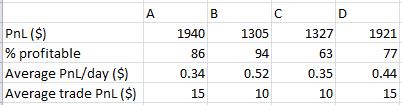

People spend so much time backtesting trading strategies but I believe without statistics, essential context is missing to make sense of it. As an example, here is some data I saw recently:

With regard to average trade, groups A and D look best but we need something more to conclusively determine. An average trade PnL of $15 for groups A and B is 50% more than groups B and C! Is that a real difference or is it likely to have occurred by chance? Sample sizes would affect our evaluation of this question as would variance within/between the groups. Inferential statistics wrap all these factors together into context we can definitively understand. Without the inferential statistics we really can’t know much at all.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (1) | PermalinkAn Argument for Statistics (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on December 17, 2015 at 07:48 | Last modified: November 6, 2015 08:50Most people who know anything about statistics understand descriptive ones: numbers used to summarize and describe data. I feel strongly that as traders, we need to understand inferential statistics too.

Inferential statistics are used to reach conclusions that extend beyond the immediate data alone. These might be used to infer from a sample characteristics about the whole population.

Inferential statistics are also used to determine whether an observed difference between groups is dependable or simply a chance occurrence. This is called hypothesis testing.

I said one could lie with descriptive statistics by including certain things and excluding others.

Inferential statistics may also mislead by including/excluding certain differences/similarities in experimental design. Even before hypothesis testing begins, validation of experimental design is essential albeit beyond the scope of today’s post.

Hypothesis testing begins by defining the hypotheses. The null hypothesis (Ho) generally states that both (all) groups are the same. The value of a group is often given in terms of an average (e.g. arithmetic mean) and standard deviation. The null hypothesis represents the status quo. The alternative hypothesis (HA) generally states the groups are not equal. HA may or may not go one step farther and state which group is thought to be greater than the other.

The next step is to consider the statistical assumptions being made about the sample(s) involved. For example, a given statistical test may require the samples be independent (e.g. not affecting each other) or that the distribution (shape) of a sample be “normal” (bell curve, which has a specific mathematical definition), etc. If the assumptions for a statistical test are not met then the test should not be used or the caveats/limitations should be discussed to put reasonable context around any conclusions.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (3) | Permalink