Transaction Fees and Backtesting (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on August 17, 2017 at 06:28 | Last modified: May 25, 2017 14:01My last post discussed reasons to cut back from my $26/contract transaction fee assessment. Today I want to finish up by discussing further implications of transaction fees.

A back-of-the-hand calculation suggests that if I cut transaction fees by Y then I can expect an average trade of X + Y where X was the average trade with transaction fees of $26/contract.

The relationship between transaction fees and PnL is more than linear, though. If I were to repeat the bullish iron butterfly (IBF) backtest with lower transaction fees then I could expect all the winners to remain winners. Days in trade would decrease, though, and this is the wild card.

Being in the trade for a shorter period of time reduces exposure to the IBF’s biggest enemy: big market moves. Some may argue IV spikes are the biggest enemy but the two are usually coincident.

Big market moves will damage prospects most for losing trades with highest MFE. MFE often occurs just before a big market move. In these cases, the move happens and the market never looks back thereby pushing these trades to max loss. Losing trades with MFE near the profit target have the best chance to become profitable given lower transaction fees. Confused? Consider the opposite extreme: losing trades with [lowest possible] MFE equal to initial PnL won’t have a chance regardless of transaction fees because these trades never get off the ground. For the IBF, initial PnL = -8 * transaction fees/contract.

Thought about differently, lower transaction fees means the initial PnL is greater, which means fewer days of theta decay required to reach the profit target. I could sort losing trades by MFE to approximate how many trades might benefit.

I need to make sure MFE is tracked correctly in order for this to be useful. I defined MFE as the highest intratrade PnL before expiration. I questioned this metric a couple times while backtesting. Once I suggested tracking MFE after profit target was hit could be useful. Another time I suggested tracking MFE before MAE was hit. If using stop-losses then it might be useful to know MFE before the stop-loss is hit (a better MFE afterward would be meaningless with the trade already closed).

All things considered, I think the MFE methodology is satisfactory given the need described above.

With the goal of cutting transaction fees significantly by being patient with trade entry, counting trades with MAE DTE equal to initial DTE will suggest what percentage of the time this could work. These would be the trades that recorded zero MAE (although as discussed in the last post, the opportunity would still exist to be filled intraday due to usual price volatility).

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (0) | PermalinkTransaction Fees and Backtesting (Part 1)

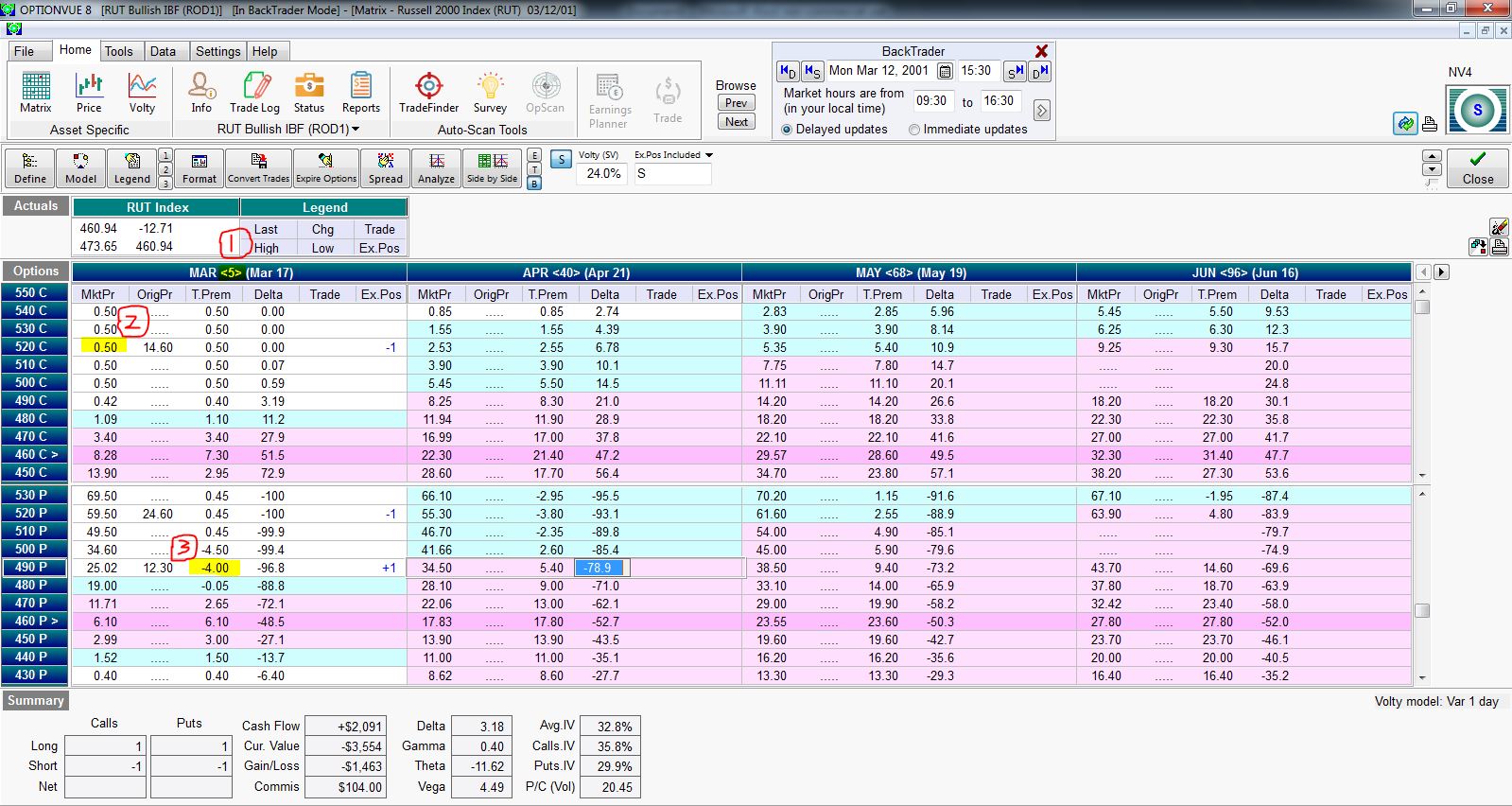

Posted by Mark on August 14, 2017 at 07:11 | Last modified: May 25, 2017 07:10I began analyzing the data from my bullish iron butterfly (BIBF) backtest in the last post. The initial results were surprisingly poor so I want to detour and reopen the discussion about transaction fees.

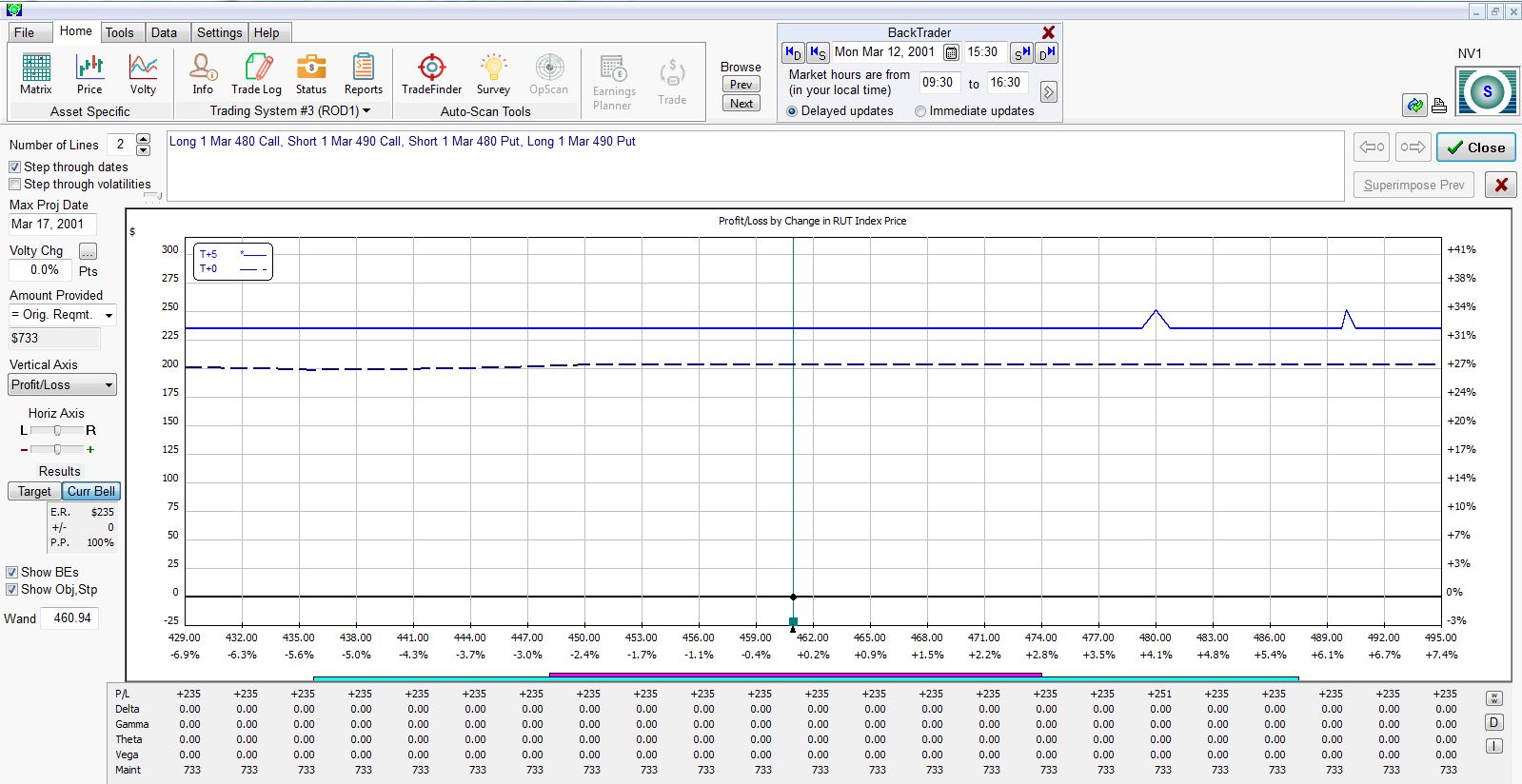

Conservative assessment of transaction fees contributed to making this trade look worse than it might actually be. I also discussed this with regard to the dynamic iron butterfly. I set transaction fees to $26/contract or $208 for the whole trade. The average trade was about -$150; if I were able to do the trade for $6/contract (a nickel slippage per leg) in transaction fees then the average trade would improve to +$10. Suddenly this trade would be worth considering.

A case can be made for significantly less slippage upon exit. I spoke last time about how live trading a losing butterfly would result in significant savings: perhaps knocking transaction fees down from $104 to $30. Another example regards a profitable trade. As expiration approaches, the long legs usually decay to zero. In many cases they are worth only a nickel or dime when the profit target is hit. Rather than closing these at a cost of $26/contract, I would let them expire and save the difference.

Leaving the longs to expire also offers some end-of-cycle crash insurance were the market to make a huge move as expiration approaches. With the shorts already closed at the profit target, the longs remain risk-free. My backtesting does not take this into account. In order to see if the detail is material, I could look for big differences in maximum adverse [favorable] excursion with 2-4 DTE and the expiration PnL to get a sense of how often big moves occur in the final week.

Trade entry is another opportunity to mitigate slippage. A limit order placed at the midprice is likely to be filled within a few trading days due to the usual fluctuation in market prices. Studying MAE distribution would help to quantify this. Any trade that registers a MAE larger than -$416 is effectively a zero-slippage trade.

I am most interested to see what percentage of trades has MAE less than -$416 because these are the ones that may not fill. The risk of going unable is actually lower, though, because opportunity exists for intraday drawdowns to occur that also represent zero-slippage entries. Intraday backtesting is very time intensive so the best way to understand this is through live trading. Even if I were to use OptionVue for intraday backtesting, it only offers limited data (every 30 minutes).

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (2) | PermalinkBullish Iron Butterflies (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on August 7, 2017 at 07:09 | Last modified: June 9, 2017 09:02Today I begin my report on the bullish iron butterfly.

The structure of this trade is different from the dynamic iron butterfly. This trade was centered 2-3% above the money (split strikes were used if necessary). Also, this was a balanced (e.g. symmetrical) butterfly. The last backtest only included a few balanced butterflies [when the dynamic criterion so ordered].

Trades were held until a 10% profit target was hit on an EOD (3:30 PM ET) basis or until expiration Thursday. I assessed my usual [arguably excessive] transaction fees.

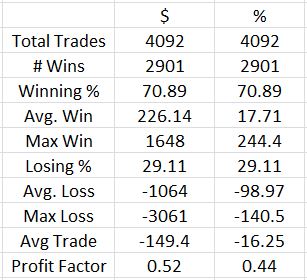

Here are the initial results:

Aside from the ugly profit factor, the first thing I noticed was a max loss of -140.5%. In live trading, the worst loss I would incur on this trade would be a case where one spread goes DITM. OptionVue often shows these spreads to be worth more than their width. While this could potentially happen under low-volume, illiquid conditions, I would never actually close such a spread. Rather, I would hold it until expiration and pay two assignment fees. With this totaling $30 (or less) and the minimum margin requirement ever recorded of $400, the worst loss I could ever technically incur would be -108% ($430 / $400).

For this reason, I went back and changed the max loss on any trade to -108%:

The effect of the changes was minimal. 176 additional trades showed a loss between -108% and -115% but based on the minor impact from mitigating the most extreme losses, I don’t think it’s worthwhile going back to change the others.

I’m just getting started with this backtesting analysis but I do not think this is an optimistic start! Between 2001 and 2017, I backtested the bullish iron butterfly through many market environments and conditions. While I will separate some of these out and compare in an attempt to identify differences, part of me believes a robust trade should backtest profitably on the whole. This clearly did not.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (2) | PermalinkBacktesting Frustration (Part 6)

Posted by Mark on July 13, 2017 at 05:46 | Last modified: March 5, 2017 09:10This has been a very beneficial exercise in expository writing because at the outset I was not sure I would ever get through. One question remains: why bother backtesting 2001 – 2003 if this part of the database has so many holes?

2001 – 2003 presents a critical sampling of different market environments. The 9/11 crash is followed by a sharp bullish reversal into January 2002. From April 2002 to July 2002 the market fell 29% before falling 20% from August 2002 to October 2002. The market then rallied 63% from March 2003 through December 2003. These may be the only occurrences in the database of such wide-ranging action at low market prices. And even if they weren’t the only occurrences, the total number of occurrences is small enough to make each one critically important.

I feel better having gotten all of this frustration out in writing.

With regard to the abandoned butterfly backtest, I think I will simply the column headers and take it a smaller chunk at a time. As mentioned earlier, I am trying to accept that my backtesting will take much longer than it probably should. This will be one of those cases but at least it will get done and hopefully from it I will get some very insightful analysis.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (0) | PermalinkBacktesting Frustration (Part 5)

Posted by Mark on July 10, 2017 at 07:10 | Last modified: March 5, 2017 08:40Given everything I said about spotty/flawed data, and the occasional need to manually add additional strike prices, starting later would probably be better. This presents another set of backtesting problems that I will discuss today.

Starting the backtest where I know the database is more complete (e.g. 2005) would result in fewer workarounds, fewer holdups, and faster overall progress. By shifting the hardest work to the end, this would serve as an effective antidote for much of the frustration I have been discussing in this blog mini-series.

Unfortunately, in order to generate an equity curve I need to start at the beginning. The process records account value every trading day to allow any errors to be immediately identified and fixed, which preserves integrity of the curve. Also as a cumulative summation to date, an equity curve does not even make sense without all previous trades being logged.

In order to get through, I have just been trying to accept that the research will take much longer than it probably should. I go through the 16-year database once to perform the backtrades. I then go through the database again to record equity values. I can’t do it all together when my attention is split in so many different directions trying to keep up with what statistics to record (dictated by the column headers), filling in missing data, and sometimes reviewing for data accuracy. The harsh reality is that a second time through can easily add 2-4 weeks on top of what has already been 2-4 months.

Backtesting stop-losses presents a similar conundrum. This is what inspired the current blog series after frustration forced me to abandon my last butterfly backtest. I tried to include stops in the column headers so I could watch for them every trading day. I was monitoring two profit targets, two stop-loss levels, and MAEs for multiple open trades in a spotty portion of the database. My cognitive capability was simply overwhelmed.

One could argue the most accurate way to collect stop-loss information is to first record MAE for all backtrades and then filter by different stop levels (e.g. 1x, 2x, 3x) to later go back and retest only those trades reaching the different levels to determine the actual end-of-day losses.

While it may be accurate, it certainly is not efficient or fast. I hope OptionVue can help me more with that as time goes by.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (1) | PermalinkBacktesting Frustration (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on July 7, 2017 at 06:48 | Last modified: March 3, 2017 05:17Today I continue to hack my way through this difficult exercise of putting into words exactly why I sometimes find backtesting to be paralyzingly frustrating.

And yes, that really is a word:

(sorry but some periodic comic relief along with that candy are what it’s taking to get me through a subject like this)

Flawed data decreases backtesting accuracy by an indeterminate amount. I do not realize the data is flawed so I don’t know how often errors occur, to what extent, and therefore how large the impact. The reason I don’t routinely screen for inconsistencies is because a backtest is usually thousands of trades that will already take months to complete. Scrutinizing every historical day would take much longer. Besides, I shouldn’t have to do this. I pay a lot for OptionVue (OV) because I trust they offer a valuable tool. If I cannot trust the data then what good is the software?

In addition to being occasionally flawed, the OV data is spotty at times (especially 2001 – 2003). Missing data must be filled in with theoretical prices (less accurate) but when theoreticals are not available I have to enter prices manually based on a logical vertical volatility skew. This adds 2-3 minutes per historical day.

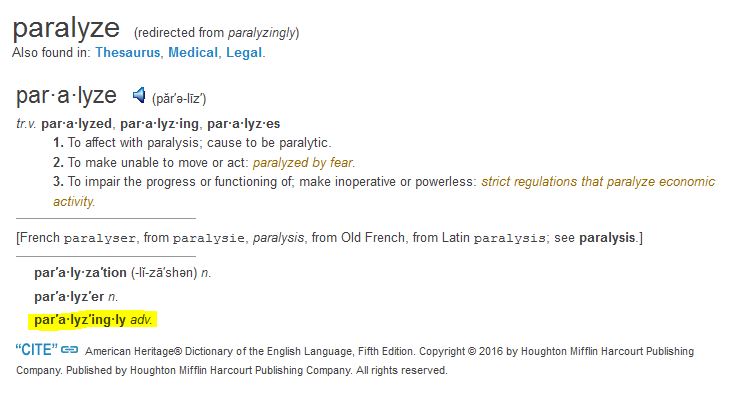

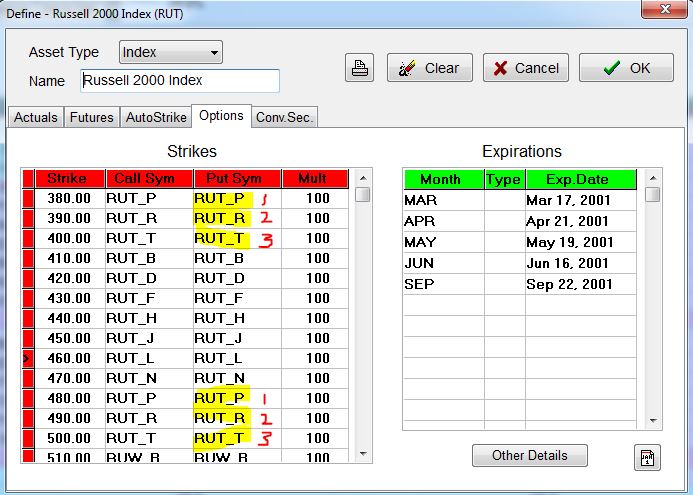

I also have to deal with insufficient strike availability. Consider below with the underlying at $460:

My backtest will require options down to 410 and sometimes 380. When I manually add these:

OV automatically duplicates root symbols (see red numbers), which results in flawed (duplicated) option prices:

So when forced to add strikes manually, I need to fill in with root symbols that I may not know. Sometimes I jump to a portion of the database I feel confident will have options in that range to determine the correct letters. For example, if I need strikes in the 300s then I can try jumping ahead to September 2001 where the underlying fell into the 300s to find out what letters were used. Once entered, I have to turn off the “Auto Strike” feature to prevent OV from resetting the matrix (automatically done on the first trading day of every week), which would thereby delete the additional work I have done—additional work that takes minutes, by the way.

And realize this problem is all secondary to the primary issue of an incomplete database.

I mentioned above that a backtest usually includes thousands of trades. You can imagine how tremendously frustrating it is to be repeatedly slowed down like this.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (1) | PermalinkBacktesting Frustration (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on July 3, 2017 at 06:14 | Last modified: March 1, 2017 10:36Today I will continue discussing backtesting frustration specific to the OptionVue (OV) software.

My third issue is difficulty obtaining accurate margin requirements (MR). The Status window is an excellent piece of functionality that shows, at a glance, desired statistics for all open trades. Only sometimes do I get an accurate MR here, though. Technical support has told me that margin in OV pertains to short options. Debit trades, like the butterfly, do not necessarily have an associated MR. That does not explain why it intermittently works for me, though.

Rather than carving out certain types of positions on which to calculate margin, my preference would be a renaming to something like “buying power reduction” (BPR). All trades reduce buying power and if BPR exceeds the value of my account then I get a margin call: plain and simple. Knowing the BPR will allow me to calculate ROI, which I sometimes like to do.

Another suggestion is a more continuous tracking of MR throughout the course of the trade. At any given time, OptionNET Explorer—another software package in the options analytics space—displays two MRs: current cost and the maximum margin ever recorded. This would be useful to know because while trades have varying levels of margin, holding the maximum margin ever required on the sidelines offers a better chance of maintaining every trade to completion. I believe ROI should be calculated on maximum margin for the same reason. ROI will be diluted since most trades will not reach maximum MR but in live trading, it would be reckless to position size without having full reserve capital available for a worst-case scenario that will happen given a long enough investing horizon.

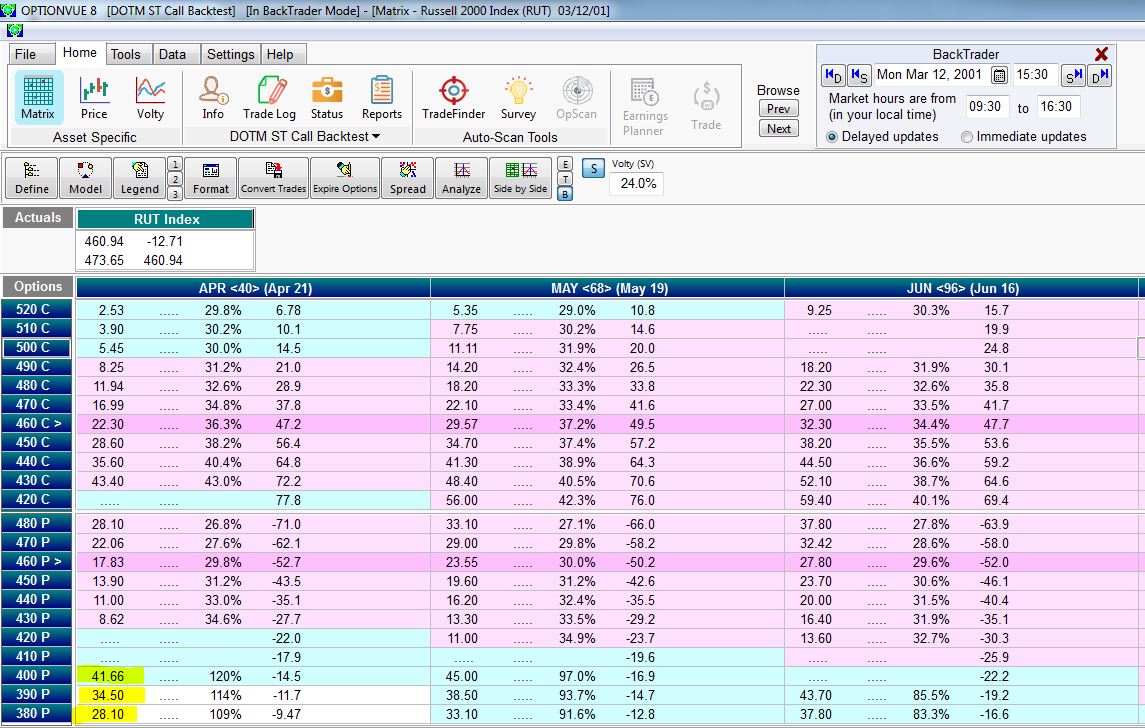

OV issue #4 is truly paralyzing for me at times: flawed and inconsistent price data. I have found the latter portion of the database to be pretty reliable. My concern is chiefly 2001 – 2004. Check out the following matrix screenshot:

I have highlighted three problems in this matrix:

(1) has to do with the DTE calculation (five days shown for this expiration Monday), which I discussed last time.

(2) refers to the fact that the 500 – 540 calls are all priced at $0.50. This is bogus. Pouring salt on the wound is the fact that the 490 call is priced even lower. If this were ever true then the 490 would be bought and any/all of the 500 – 540 calls would be sold for a guaranteed profit until the price discrepancy went away.

(3) shows the 490 put with -$4.00 of time premium. If that doesn’t make sense to you (it didn’t to me) then recognize the option is ~29 points in the money and priced ~$25. If this were ever true then I could trade a box spread (bull put and bear call vertical spreads at the same strikes) for a guaranteed profit:

As some guru used to say, if trading were that easy then it would be called winning.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (0) | PermalinkBacktesting Frustration (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on June 29, 2017 at 07:12 | Last modified: March 1, 2017 10:03I left off talking about spreadsheet headers, which really define the whole backtesting project. Today I will continue by discussing some frustrating aspects of the OptionVue (OV) software itself.

Having opened for business in 1983, OV has more tenure in the “high-end options analytics” space than any other company. A more recent newcomer to the space is OptionNET Explorer. ThinkorSwim brokerage also has some backtesting functionality through its thinkBack module.

None of these software packages support automated backtesting. This would be a process by which I could define a trading system/guidelines and have the software automatically process the entire trading interval with an output of results in seconds (e.g. AmiBroker for stock/futures trading systems).

Since a delay is incurred to update the matrix (i.e. options chain) whenever I switch time or date, my approach is to enter a new backtrade on each trading day. To maximize efficiency, I try to monitor/record necessary statistics for each open trade while the data is loaded for that date. This includes PnL and anything else specified by the column headers.

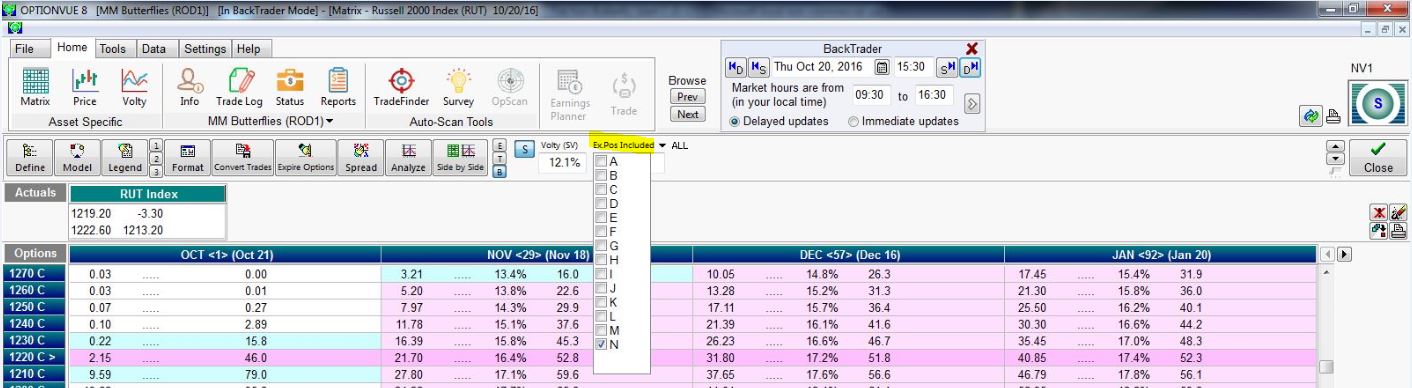

Frustration #1 regards buggy R-codes (see last post), which has gotten worse over the last year’s worth of software updates. Positions displayed in the matrix are shown in the “Ex.Pos Included” field or checked in the pull-down menu:

I used to be able to quickly scroll through open trades by typing the corresponding letter, number, or symbol into the Ex.Pos Included field (obstructed in this screenshot by the pull-down). I am now limited to letters and I often have difficulty entering them with keystrokes.

You can also see the “ALL” selection that toggles with “NONE” by clicking on the arrow. The “APPLY” button is only available intermittently and not in the current screenshot. If I try checking select positions, “ALL,” or “NONE” when the button is not available then I cannot move forward.

Issue #2 regards the days to expiration (DTE) calculation. When Backtrader is set to 2001 – 2002, DTE is calculated based on expiration Saturday. As far as I know, these options have always expired on Friday. The software is inconsistent as to when it changes DTE calculation from Saturday-based to Friday-based. When I tested this yesterday it was on 1/3/03. Today it happens on 1/13/03.

Either way, I have to remember whenever I visit the early portion of the database to check DTE in my head for consistency. Sometimes I will forget this for a few historical weeks/months and be forced to go back and modify every DTE number for affected trades. Cue additional frustration.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (0) | PermalinkBacktesting Frustration (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on June 26, 2017 at 07:42 | Last modified: February 27, 2017 10:56On Saturday I started a backtest. I only got through 15 minutes before I quit in frustration. Today I want to explain why this happened and possibly flush out some insightful principles about the backtesting process as a result.

This is going to be a tough blog post to write. I just went for a dark chocolate mint 3 Musketeers bar. If I had candy corn here then I would have grabbed that. My best friends know what this means. Everyone else can probably guess.

I have brainstormed a good 1,200 words on this subject and full explanation of some of these concepts could be a lot lengthier. Some of these are lines of thinking having to do with statistics, trading system development, software, and intraday vs. end-of-day trading. If I can succeed in presenting the material in an organized fashion then at the very least it should be good fodder for discussion. At most it may serve as dynamic teaching material.

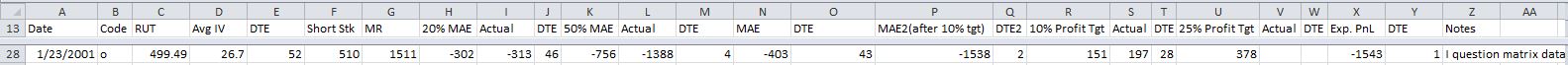

My first hassle when it comes to backtesting is how to label spreadsheet columns. What may seem like a simple detail really defines the whole thing. For the next few (to several) months I will be looking for and recording data defined by the column headers. If I get to the end and realize I forgot something critical then I may bang my head because I’ll be looking at months of additional work to go back and gather information rather than a few extra seconds per backtrade when I had the proper information on the screen.

My intent this past Saturday was to backtest a symmetric butterfly strategy. Here were the column headers I chose:

Font too small? Welcome to my world of squinting eyes. If I make it bigger then fewer columns fit on the screen at once and I have to use the scroll bar to enter routine data. Each second this adds gets multiplied by up to 4,000 backtrades, which also gets multiplied by two (back and forth).

Column (“Col”) A is date of trade inception. Col B is a letter code used to identify each day’s trade from all the trades currently in the transaction log. In OptionVue (the software I use) parlance this is called the R-code. Col C is the underlying price, Col D is the average implied volatility for all options in the chain, Col E is days to expiration (DTE), and Col F is the short strike for this position. Col G is the initial margin requirement for this position.

I have covered enough ground to explain some frustrations I have with the software itself. I will pick up here next time.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (5) | PermalinkButterfly Backtesting Ideas (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on June 12, 2017 at 06:23 | Last modified: February 22, 2017 10:02I have completed one exhaustive butterfly backtest on dynamic iron butterflies (DIBF). While helpful for offering up some context, it left much to be desired.

Butterflies seem to be all the rage in trading communities these days so the main reason my backtest failed to impress is because the results were inconclusive. Slippage really made the difference between a trade that was profitable and one that was not. While tantalizing to think I can overcome slippage by simply entering a GTC limit order and waiting for a fill, unables do occur. Backtesting cannot fully determine the impact of unables primarily due to limited granularity of data (30-minute intervals).

I have some methodological issues that may have negatively impacted the results. The dynamic nature of the strategy means some trades were symmetric and others were asymmetric. An asymmetric butterfly will have a lower max loss potential to the upside. Even though most losses seem to have taken place on the downside, having a much larger upside loss potential (100%) hurts because the downside loss potential is the same either way (100%).

Aside from some trades being symmetric, those that were not had varying degrees of asymmetry. The greater the asymmetry, the lower potential loss to the upside in terms of ROI (%). Perhaps this should be standardized.

The need for standardization feeds directly into the next issue: use of percentages (ROI) instead of PnL. Because margin requirements ranged from $1,401 to $12,400, I used percentages to avoid having to normalize (e.g. two contracts of a $5,000 trade equates to one contract of a $10,000 trade). ROI is unaffected by margin requirements. Now consider a downside loss. Asymmetric and symmetric butterflies can both experience -100% ROIs when PnL is [much] worse for the asymmetric due to the embedded put credit spread. This doesn’t feel right.

One thing I could do with the DIBF backtest is normalize for margin requirement then recalculate the trade statistics based on PnL. This might serve as confirmation that I was on the right track with the initial analysis.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (0) | Permalink