Investing in T-bills (Part 11)

Posted by Mark on March 6, 2024 at 10:32 | Last modified: April 3, 2024 09:51The original plan was to finish discussing considerations about synthetic long stock (SLS) + T-bills versus long shares and then crown a winner. Due to the Part 8 revelation that advantage of the former is < 0.5% (further discounted by fees as discussed last time), I now regard other considerations to be moot. I will continue going through them for educational purposes only.

In the spirit of completeness, the <0.5% calculation should be replicated. I did this using data for the 5275 strike with the underlying around 5235. For a better sampling, I would like to look at strikes 50 – 200 points above and below the market by increments of 50. New data should be used because more than 10 days have passed and SPX no longer trades at the same level. This exercise is important to ultimately crown a winner.

I discussed liquidity of SPY options last time but also expressed assignment concerns in this third paragraph—a concern minimized by trading SPX options (see that second-to-last paragraph).

With regard to taxes,* two issues become comingled: SPY versus SPX options and holding period.

Pertaining to holding period, realize SLS includes a long call and short put that are each taxed differently. This Schwab article says capital gains** on the former will be long-term (short-term) when held for over (equal to or less than) one year. Income from the short put will be short-term (“ordinary income” tax rates, which are higher than long-term capital gains rates). The combined SLS will be taxed less for a long-term holding period (albeit implying longer-term options that face more slippage as mentioned in the fourth paragraph of Part 10).

Next, realize that SPX options (Section 1256 contracts) get special treatment regardless of holding period: a blended 60% long-term / 40% short-term capital gains tax rate. The SPX short put will benefit when profitable from the blended tax rate. A profitable SPX long call will benefit when held for less than one year (else the blended tax rate may actually be higher).

Even with SPX options taxed less than SPY options, both will be taxed more than buy-and-hold (i.e. holding period over one year) SPY shares. The latter will be taxed at long-term capital gains rates and only when sold. The blended 60% / 40% rate for SPX options is higher and will be assessed every year (mark-to-market accounting for Section 1256 contracts). Thinking about the RMD disadvantage of a traditional IRA compared to a Roth IRA (see Forbes article here) makes me realize the tax efficiency of waiting until sale to be taxed on the whole enchilada rather than being taxed continually on component parts.

As a general statement, I believe taxes make a meaningful difference based on the number of articles I read about them (e.g. on tax cost ratio, on tax-loss harvesting, on long-term capital gains rates vs. ordinary income, on qualified dividends, etc.).

While difficult to quantify (especially until one decides how SLS holding period and DTE at inception will be managed), I’m giving the tax advantage to long shares. Along with fees, this further erodes the sub-0.5% SLS edge mentioned above.

I will continue next time.

* — I hereby share my personal experience with issues of taxation. Your circumstances

may differ and loopholes or mitigating details may exist unbeknownst to me. Please

consult a tax advisor for the definitive word on these matters.

** — Also capital losses

Investing in T-bills (Part 10)

Posted by Mark on March 5, 2024 at 14:26 | Last modified: April 2, 2024 07:56I think the realization discovered in Part 8 will prove to be the climax of this blog mini-series. Today I am going to briefly discuss liquidity and transaction fees.

Pertaining to slippage, option liquidity would be important when looking to sell shares and trade the synthetic long stock (SLS) in addition to T-bills. I now know the potential benefit is < 0.5% per year (from Part 8), which may make doing so prohibitive. Regardless, I will proceed with the analysis.

SPY has the most liquid option market and it’s not even close. In the third-to-last paragraph of Part 5, I mention IVV and VOO as examples of S&P 500 ETFs along with SPY. At the next monthly expiration (Apr), IVV has mostly 5-point strikes, double-digit open interest at most call strikes (single-digit for most put strikes), and near-the-money (NTM) bid/ask spreads of 10-15% or more: I wouldn’t touch this with a 10-foot pole. Also for Apr, VOO has 5-point strikes, many triple-digit open interest along with some 4-digit numbers for calls and puts, and NTM bid/ask spreads close to 10%: not good. SPY has 1-point strikes for Apr, open interest of 4-5 (with the occasional 6) digits across most call/put strikes, and NTM bid/ask spreads < 1%.

Slippage is the largest of the option transaction fees—a disadvantage of trading the SLS mentioned in Part 6. Slippage will have to be paid every time SLS is rolled. This is smaller for nearer-term options (see “Total Bid/Ask Spread” column of last Table in Part 7), but nearer-term options will have to be rolled more frequently.

Other fees include:

- The CBOE “proprietary exchange fee” for products traded only on its exchange (e.g. SPX options*).

- Regulatory fees that change periodically but will be passed through to the customer by most brokerages.

- Commission rates that vary by brokerage.

Tasty Trade gives a great example of how these fees add up (reprinted here in case the page should be removed):

> SPX TRADE EXAMPLE

>

> 2 short 3000-strike Call: $30.50 credits

> 2 long 3020-strike Call: $21.50 debit

> Total Credit Received: $9.00 per spread

>

> Cost to Open

>

> Sell to Open: -2 short 3000-strike calls

>

> Commission: $2 ($1/contract)

> Clearing: $0.20 ($0.10/contract)

> Options Regulatory Fee: $0.0581 ($0.02905/contract)

> SEC Fee: $0.1769 ($0.0000229 x 2 x 100 x $30.50)

> Proprietary Index Fee: $1.30 ($0.65/contract)

> Total: $3.7132

>

> Buy to Open: +2 long 3020-strike call

>

> Commission: $2

> Clearing $0.20

> Options Regulatory Fee: $0.0581

> Proprietary Index Fee: $1.30

> Total: $3.5583

>

> The total cost to OPEN the spread: $7.2715

>

>

> Cost to Close

>

> Three weeks later, position is closed for a $3.00 debit, resulting in a $6.00 profit per spread.

>

> 2 short 3000-strike Call: $6.00 debit

> 2 long 3020-strike Call: $3.00 credit

> Total Debit: $3.00 per spread ($600 total debit paid to close)

>

> Buy to Close: -2 short 3000-strike calls

>

> Commission: $0

> Clearing: $0.20 ($0.10/contract)

> Options Regulatory Fee: $0.0581 ( $0.02905/contract )

> Proprietary Index Fee: $1.30 ($0.65/contract)

> Total: $1.5583

>

> Sell to Close: +2 long 3020-strike call

>

> Commission: $0

> Clearing $0.20

> Options Regulatory Fee: $0.0581

> SEC Fee: $0.0174 ($0.0000229 x 2 x 100 x $3.00)

> Proprietary Index Fee: $1.30

> Total: $1.5537

>

> The total cost to CLOSE the spread: $3.112 ($0 commission + $3.10 fees)**

Option transaction fees will further erode the < 0.5% per year edge for trading SLS. With long-term buy-and-hold share positions, minimal fees may only be incurred when opening and closing while equity commissions are often zero these days (consult your brokerage).

I will continue next time with a brief mention of taxes.

* — Whether to trade SPY (third paragraph) vs. SPX options is an entirely separate debate.

SPX is a very liquid market especially for institutional traders.

** — Fees for this trade amount to ($10.384 * 100%) / [($20 * 100 * 2) – ($900 * 2)] =

0.47% of total capital allocation.

Investing in T-bills (Part 9)

Posted by Mark on March 4, 2024 at 10:59 | Last modified: April 1, 2024 10:04The revelation from Part 8 is the hidden cost associated with synthetic long stock (SLS).

To explain this, I now think in terms of an argument that posits edge being arbitraged away once discovered by the masses. T-bills pay annualized interest ~5%: much higher than the default return on cash (currently 0.35% as stated in this second paragraph). This would drive the masses to sell stock, buy calls (or SLS), and invest the capital difference in T-bills. The resultant buying (selling) pressure on calls (puts) would put upward (downward) pressure on call (put) option prices. As seen here, calls end up more expensive than puts.

Nasdaq.com explains this in terms of stock investors who buy on margin:

> When interest rates rise, the cost of borrowing money to buy

> stock on margin increases. For example, if you want to buy

> $10,000 worth of stock on margin, the cost to use margin

> is much higher when interest rates are at 5% vs. 2%.

>

> Therefore, a trader may look to buy a call option to avoid this

> increased margin interest. For this reason, the pricing of call

> options will rise when interest rates are hiked…

>

> The options market reacts to interest rates, causing call options

> to increase in value. Instead of buying $10,000 worth of stock

> on margin, a trader can purchase a call option to benefit from

> the same upside with much less capital, say $1,500.

>

> The saved $8,500 can be put into a risk-free asset such as a

> T-bill to generate interest, allowing the trader to benefit from

> the potential upside of a stock and generate income with a bond.

>

> Due to the traders’ ability to generate a risk-free return on this

> saved capital, the price of call options increases. There is no

> free lunch in the stock market, so when opportunities like this

> arise, it will reflect in the price of call options.

Investopedia explains the decreased put premiums as follows:

> Theoretically, shorting a stock with an aim to benefit from a price

> decline will bring in cash to the short seller. Buying a put has a

> similar benefit from price declines, but comes at a cost as the put

> option premium is to be paid. This case has two different

> scenarios: cash received by shorting a stock can earn interest

> for the trader, while cash spent in buying puts is interest

> payable (assuming the trader is borrowing money to buy puts).

>

> With an increase in interest rates, shorting stock becomes more

> profitable than buying puts, as the former generates income

> and the latter does the opposite. Thus, put option prices are

> impacted negatively* by increasing interest rates.

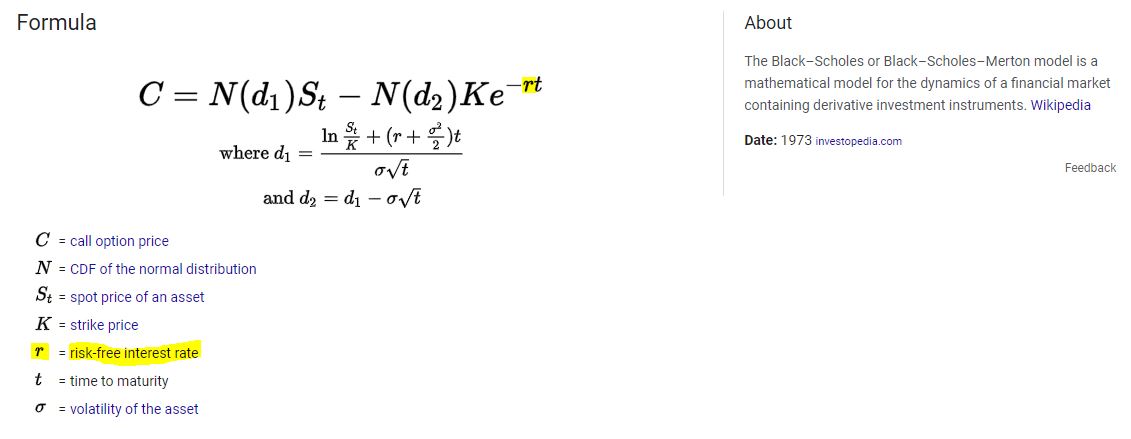

Interest rates are actually part of the Black-Scholes model of option pricing. Again, per Investopedia:

This shows call pricing as a function of two complex terms. The second term is subtracted and interest rates (greek letter rho highlighted in yellow) are in the denominator of this second term. As interest rates increase, the denominator increases thereby reducing the second term leaving—since less ends up being subtracted—a higher call price.

I will continue next time.

* — Lower demand can negatively impact put prices.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkInvesting in T-bills (Part 8)

Posted by Mark on March 1, 2024 at 11:41 | Last modified: March 28, 2024 13:54The last table in Part 7 shows pricing data for synthetic long stock (SLS) positions in SPX: a combination of different expirations and strike prices. This brings me to a shocking revelation.

Walking the chain reveals loss from holding the SLS position. This means looking forward in time to get an idea what pricing will be like if “all else remains equal.” 91 days from now, the Sep position—now 182 DTE with a cost of $76.90—will be 91 DTE. Looking at the 91 DTE option chain (hence “walking the chain”) today (Jun expiration) shows the Jun 5275 SLS costs $21.10. 63 days after that, the Sep position would be like today’s Apr position with 28 DTE: established for an $18.40 credit. What I originally purchase for $76.90 will cost me an additional $18.40 to close in 154 days. That represents a loss of $76.90 + $18.40 = $95.30 or $9,530 per contract.

Say what?

The risk graph provides confirmation:

The purple line on 3/21/24 shows a current PnL of -$219.59. The cyan line on 9/21/24 shows a PnL in 182 days of -$11,609.10. This is a loss of $11,389.53. The SLS saves $523,599 (cost of 100 shares) – $7,690 (cost of SLS) = $515,909 for a [all-else-remains-equal] cost of (11,389.53 / 515,900) * (182 / 365) * 100% = 4.43%/year of the capital saved.

Let’s review.

I have been exploring the idea of trading SLS + T-bills as a way to get equivalent long stock exposure and bond interest.

I just discovered that trading the SLS incurs a cost that offsets much of the interest paid by T-bills.

What we have is another instance [so often heard when studying investing/trading/finance] of “no free lunch.” Also coming to mind is “can’t eat your cake and have it too.”

I had been starting to think trading SLS and investing in T-bills might provide an edge over buying the long stock outright. Rather than a potential edge to be had, I now see it more like a detriment suffered if T-bills are not purchased while holding the SLS. As an option trader with lots of free cash, T-bills must be purchased to avoid missing out on what is basically free money. As a more traditional equity investor, while T-bills still appear to be the better deal (by roughly 0.47%), I’m not convinced going the SLS route is worth doing given the remaining considerations when comparing the two.

I’d be lying if I denied any presence of sour grapes right now. The Options Playbook says:

> For… [SLS], time decay is somewhat neutral. It will erode the value of the option

> you bought (bad) but it will also erode the value of the option you sold (good).

Nothing could be farther from the truth in today’s environment.

I will continue next time exploring why this might be.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | Permalink