KD or the Retail Trader? (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on June 29, 2021 at 06:13 | Last modified: May 25, 2021 07:49Motivation for this post is an e-mail I received from “NS” expressing interest in working together to develop trading strategies. You be the judge as to whether the ultimate takeaway is particular to KD or a statement about retail traders in general.

I introduced KD in the second-to-last paragraph here. As part of his offerings, he created a “strategy collaboration spreadsheet.” This is a networking tool for anyone interested in working with others to develop trading strategies.

Collaboration has been discussed many times in this blog (i.e. here, here, here, and here).

The e-mail I received from NS reads:

> Hi Mark,

>

> I am a father of 3, Husband, CEO, Systematic trading enthusiast. Traded

> stocks discretionary for 12 years, have been trading stocks systematically

> for 1yr Looking for a partner to join forces for accountability and

> collaboration to complete new strategies. What is your availability for

> an introduction meeting?

>

> [corporate signature]

While I continue to search for collaboration, I got an ominous feeling from this e-mail. Kudos to NS for introducing himself and providing some personal background. I just didn’t know how he found me. I have been away from the KD world for over a year. Did he read my blog and message me through the website? Was he someone I contacted in the distant past? Did he get my name from a third party? NS’s e-mail felt totally out of the blue.

After some deliberation, I responded:

> Hi NS,

>

> How did you get referred to me?

>

> Thanks,

> Mark

This ends in a very interesting way, which I will get back to later.

When I purchased KD’s “Y” (a brand name that will remain masked), I added my name to the collaboration spreadsheet and started e-mailing people. Over the course of 4+ months, I reached out to 12 people from the spreadsheet. For those who did not respond at first, I sent a follow-up two weeks later “in case they missed” the original. This was my message:

> Hi X,

>

> I am contacting you from the Y collaboration spreadsheet. I’m

> looking for someone with whom to exchange ideas, feedback,

> impressions, test strategies, etc.

>

> I hope you’re making it through this COVID-19 crisis okay!

>

> Thanks,

> Mark

The difference between my e-mail and the one I received from NS is mention of Y. Y should be easily recognizable because everyone paid a lot of money to get it. This makes us a shared community. Y should provide for a warm lead—at least warm enough to warrant a short response from those not interested and/or an explanation of why (since they did voluntarily add their name to the spreadsheet in the first place). Nobody owes that to me, of course, but for some I tend to think “common courtesy” would include it.

How exactly did I fare with my outreach attempts?

I will continue next time.

Categories: Accountability | Comments (0) | PermalinkCall Me Crazy (Part 7)

Posted by Mark on June 24, 2021 at 07:43 | Last modified: May 31, 2021 11:02Last time, I discussed the risk to long calls (LC) posed by flat/down years on the stock market. Today I want to turn up the volume a bit by considering multi-year weak markets.

A multi-year bear market is one of my greatest fears because LC loss will be additive from one year to the next. Part 6 includes a table where I isolate the down and flattish years from my 14+ year backtest. Only in 2007-2008 do we see back-to-back down/flattish years. This does not hurt the LC account very much because 2007 ends roughly unchanged. Only when I add March 9, 2009, as part of the enhanced data set do we see the 32.8% drawdown shown here. Although 2009 doesn’t end at that level, we begin to get a sense of the toll taken from consecutive down periods.

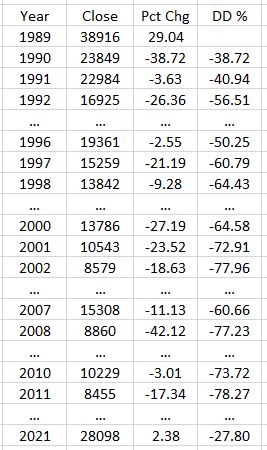

A market that declines over a series of years could result in major losses. Let’s look at Tokyo’s Nikkei index. Japan experienced a deflationary recession from ~1990 through at least 2011 where share and property price bubbles burst:

In a 12-year span, we see three instances of back-to-back-to-back down years. I can imagine a LC account down 20% in 1990, down 7% in 1991, and down another 20% in 1992 for a total hit of ~45-50%. This is an improvement over the underlying shares but still major damage. While the Nikkei average rebounds roughly 13% over the next three years, I can then imagine the LC account down 5% in 1996, 15% in 1997, and 13% in 1998 leaving it only marginally ahead of the underlying shares. Conservatively estimating a 10% each decline for 2000-2002, the LC account would pretty much go bust (worse than the underlying shares) were I not to make any changes to the trading strategy over all this time.

The “lost decade” for our beloved SPX perils in comparison to what Japan has experienced. From the end of 2000 through the end of 2010, SPX lost 4.7%. Looking closer reveals something much tamer than the Nikkei with only four down years and five consecutive up years (2003-2007) during this period that dealt US investors so much pain.

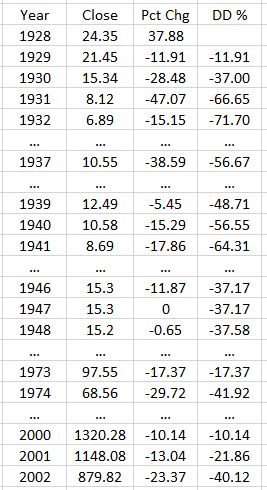

Zooming out, since 1928 the SPX has had some rockier periods:

The last row will change through the end of this year. The value shown is from May.

1929-1932 is the only instance I can find of four consecutive down years on a stock market. I can easily imagine a LC account losing 60% during this span. While this might outperform underlying shares, it is catastrophic loss nonetheless. The table also shows other cases of back-to-back-to-back down/flattish years that would really hurt a LC account invested as prescribed.

After looking at these data, I am tempted to wonder whether the last 20 years (including the entire LC backtest) hasn’t been a remarkable gift. I often hear people predicating investment theses on things like “the stock market has an upward bias,” or “the market has always taken out new highs and will continue to do so.” I don’t think it has to be this way, I sure as heck don’t think it always will, and when the next bear market sticks around for more than what amounts to a flash in the pan (COVID-19 scare in Feb-Apr 2020), I need to be be sure that my trading strategy can withstand it.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkCall Me Crazy (Part 6)

Posted by Mark on June 21, 2021 at 06:58 | Last modified: May 24, 2021 09:55I left off talking about RAR by PMDD. As impressive as this is in favor of the long call (LC) over stock shares, let’s consider the possibility that exposure isn’t everything.

Although a big difference exists between what is probable and what is possible, suitability standards for wealth management are based on the latter. The S&P 500 has never gone to zero* and I can hardly imagine a scenario where this happens in a sustainable society (I have seen fearmongers, omnipresent in the financial media, include Purge-like dystopias as part of their portrayal). Nevertheless, the possibility exists and risk models must respect it. We would otherwise be left to debate reasonable levels for maximum loss. Opinions on this differ and should we be wrong [likely, since “your worst drawdown is always ahead of you” (see third-to-last paragraph here)], the result could be tantamount to a true financial apocalypse.

[Deleveraged] Investing with insurance means we survive the worst. I’ve been in the trading trenches for the last 12+ years. Most of the time, things go smoothly. When markets get rocky, fear and stress mount fast. To have the confidence my portfolio will remain [healthy] even in the face of a total stock market collapse represents an enormous sense of security. Most substantial investors would feel the same way.

Backtesting the LC through the Great Recession appears quite encouraging.

Can we imagine a case where the strategy falters?

Consider how the LC fares in down markets. On the upside, the LC faces a performance drag in terms of upfront cost. An ATM (slightly OTM, actually) LC will expire worthless if the market does not go up. In the backtest, I purchased LEAPS two years to expiration and rolled after one. The market is marginally higher in two of the 14+ backtested years and only down in three. Is it true that overall, the LC fares better because most down years are small and/or because the LC retains most of its premium being closed with a full year left until expiration?

The second and fourth columns show % ROI for SPX share and LC accounts, respectively. The third column shows % ROI for the LC itself. Here are some observations:

- LC is battered and bruised in 2008 despite performing much better than the shares.

- LC underperformance during other four years averages 2.99% (not insignificant).

- LC average cost across all 15 periods (last being a partial year) is 16.10% (of account value).

- LC loses substantial value over first year in trade although hit to the entire account is less.

That final point has a lot to do with leverage. I have been enchanted by the limited exposure—how much firepowder remains dry—when investing with LCs. For a $100,000 account, every year offers the tempting opportunity to purchase up to 4 – 5 contracts. The last column increases proportionally to number of contracts, though. This is an ever-present threat.

I will continue next time.

* — SPX pulled back 57% from its all-time 2007 high by March 2009: the worst bear market

many of us have ever experienced, but a far cry from total 100% loss.

Call Me Crazy (Part 5)

Posted by Mark on June 18, 2021 at 07:11 | Last modified: May 20, 2021 10:36I want to continue discussing the long call backtest by understanding what it means to trade with insurance.

Trading with insurance has a few different interpretations. The long call is synthetically equivalent to underlying shares plus a long put (also known as a “married put”). Puts are commonly recognized as insurance, which few people purchase. The long call represents insurance because it controls stock shares for a fraction of the cost. These are two sides of the same coin.

Deleveraging limits loss. In the backtest (see table here), long calls return almost as much as the underlying stock shares for a much lower cost. The capital used to buy the call is the only portion of the account I can lose so long as the call is in play.

Deleveraging complicates performance comparison. Depending on reference, the long-term average stock return is about 8% (1957 – 2018 for SPX). I think many people come to believe they need 8% annually to keep pace with the market. This benchmark, however, implies a 100% stock portfolio. Who does that? A blended (deleveraged) portfolio with 60% stock returning 10% and 40% bonds returning 1.4% (average 3-month T-bill APY over last 20 years) generates an overall return of (10 * 0.6) + (1.4 * 0.4) = 6.56%. I believe many people would be unhappy, thinking this falls short of the 8% benchmark.

Given that mentality, beating the market is an incredibly difficult task. Stocks in the blended portfolio need to return 12.4% annualized to match the headline average stock return! Rumor has it most self-directed and active investors fail over the long-term. An apples-to-oranges comparison of a blended portfolio with a pure benchmark may be one reason why: people investing with greater risk in search of better returns ending up suffering outsized loss.

Those who can’t at least match the benchmarks are told to “dump it all into index funds” or “leave it to the professionals.” Regardless of what assets are included in the portfolio, the appropriate weighted average benchmark should always be used when evaluating returns. Maybe with reasonable expectations, self-directed investors would fare better.

I think significant deleveraging coupled with long-call implementation should somehow make its way into performance metrics. The call is most expensive in Jan 2009 at less than 17% of the underlying index. In 2008, the call loses no more than its then-maximum limit of 20% for the year. The long shares lose much more and could bankrupt the account on any given day. This limited exposure allows investors to sleep well at night. One way to account for this apparent safety is what I called in Part 2 “RAR by MPDD:” CAGR divided by % exposure. This is how I came up with 6.6 vs. 1.1 in favor of long calls.

Might this safety be an illusion? I will discuss that next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkCall Me Crazy (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on June 15, 2021 at 07:07 | Last modified: May 19, 2021 15:23I’ve been digging into results from my backtest on the long call versus underlying stock shares. Last time I took a deep dive into the numbers behind RAR by MDD. Today I want to move forward.

MDD is based on a single occurrence, which is one thing I do not love about the risk metric. As discussed here, large sample sizes lower the possibility of fluke occurrence. This is difficult when starting with a set consisting of only one data point per year even enhancing with 24 points of additional context. Alternatives to MDD include top three DD’s (referenced in the fifth paragraph here), average of the top three DD’s, or distribution of DD’s.

RAR by standard deviation (SD) sidesteps the single-occurrence issue by looking at overall variability. For the enhanced data set, this is 9.53 for the long call vs. 5.57 for SPX shares. This is a 1.7-fold difference compared to 1.1x (7.48 versus 6.70) in favor of the long call in the original data set. This feels right* because the enhanced data set includes additional downside volatility and was precisely the motivation for my last post.

Looking at the equity graphs in Part 3, the enhanced data set exhibits additional curve crosses. March 2020 is the real eye-opener because a substantial lead accumulated by the SPX account for over a decade evaporates in one fell swoop before completely recovering within six months. What a ride, though: adrenaline junkies rejoice! This is the opposite of what seniors or anyone with retirement in their sights want to see.

SPX hits an all-time closing high (ATH) of 1565.15 on Oct 9, 2007. I’m tempted to include this in the enhanced data set to see how it would affect the numbers. ATH is a 10.49% increase from Jan 2007 where the long call is up 8.78%. I’m guessing inclusion would mitigate the difference between original and enhanced data sets for RAR by MDD, accentuate the difference for RAR by SD, and add a couple more crosses to the equity graph.

Whether the ATH should be included is debatable. I aim to understate backtesting differences to strengthen my beyond-a-reasonable-doubt (see last paragraph here) search for viable strategies going forward. The main reason not to include is that upside volatility will not result in loss. Main reasons to include are because upside volatility is very real and because upside volatility can result in psychological loss if DD’s are calculated from a highwater mark (potential topic for future blog post).

I will continue next time.

* — What doesn’t feel so right is the impressive result that long call SD decreases from 0.141 to 0.112

between original and enhanced data sets where SPX-share SD increases from 0.160 to 0.191.

Mathematical Excursion

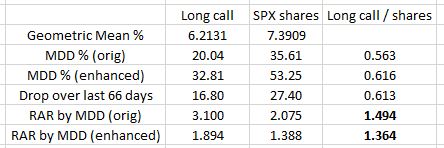

Posted by Mark on June 10, 2021 at 07:03 | Last modified: May 18, 2021 15:15I left off by explaining the difference between MAR by MDD as more extreme for the original data set than for the enhanced data set. Since this seemed counterintuitive to me, let’s take some time to explain it.

I expected long call MAR by MDD to shine even brighter compared to shares given the enhanced data set. After all:

- I used the same formula for both: (100 * Geo. Mean) / MDD %.

- Between the start of 2009 and the market low on 3/9/2009 (additional enhanced data point), the long call account dropped from $79,956 to $67,309: -16.8%.

- The SPX account dropped an even greater percentage from $65,777 to $47,757: -27.4%.

What actually matters is not whether the SPX account dropped more during the additional 66 days but rather how the drop over the additional 66 days compares to the original Jan 2008 – Jan 2009 decline. For a proportional drop in both the long call and shares, I would expect the ratio of the enhanced RAR by MDD to be the same. With 1.0 reflecting proportionality, the ratio of MDD % for long call is 0.56 for the original data set and 0.62 for the enhanced thereby suggesting the drop is closer to proportionate through 3/9/09 than it is through Jan 2009. Put another way, the more proportionate additional 66 days dilutes RAR by MDD for both the long call and underlying shares.

A table may help:

The numbers in bold are what puzzled me. The first and third numbers in the same column explain why. The ratio between MDD % is closer to 1.0 in the last 66 days, which evens out the overall comparison if only by a small amount.

Coincidentally, the ratio of the drop over those last 66 days (third number, last column) is very close to the ratio of MDD % for the enhanced data set. This got me thinking why these two numbers might be the same. They are not the same, though: 0.616 vs. 0.613. Pure coincidence.

When comparing RAR between groups, I make sure to calculate RAR in an identical manner. The idea is to divide return by some measure of risk because greater (lesser) risk should decrease (increase) RAR. I will sometimes multiply by a constant (100 in this case) to make the numbers easier to interpret. The constant doesn’t matter as long as I apply the same to both.

For these reasons, my RAR is not necessarily comparable to anyone else’s.

In and of itself, the term “risk-adjusted return” is non-specific. Different metrics for risk include alpha, beta, R-squared, and standard deviation (SD). The Sharpe ratio is a RAR metric that uses SD as its risk measure. The Treynor ratio is a RAR metric that uses beta as its risk measure.

I worried this excursion might take us out to the weeds. Indeed it has! I come back to reality (hopefully) next time.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (0) | PermalinkCall Me Crazy (Part 3)

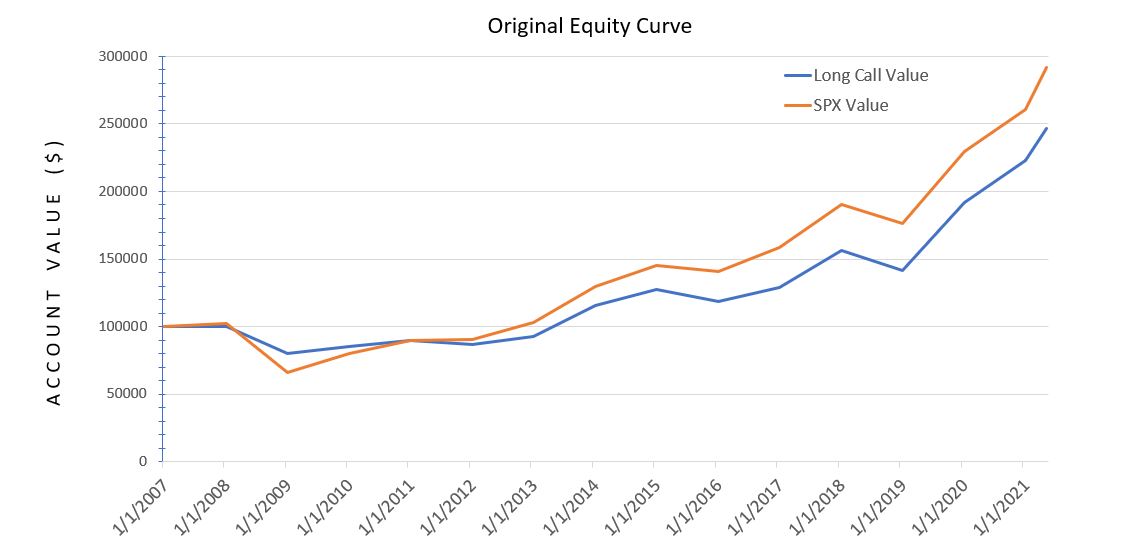

Posted by Mark on June 7, 2021 at 07:13 | Last modified: May 18, 2021 11:22Today I want to contrast backtesting results presented in my last post between the long call and underlying shares.

While mulling over the results, I questioned whether I was doing a valid apples-to-apples comparison with regard to position sizing. Initial account value was $100,000 for each yet with SPX at 1416 on 1/3/2007, the notional value of one 1425 call is not $100,000 but rather [ ( underlying price – points OTM) * 100 ] $140,700.

This apparent discrepancy is much ado about nothing. Changes in underlying account value are proportional to changes in the underlying itself, which is what I used to calculate max drawdown (MDD). MDD may be calculated as a percentage, thereby normalizing for any scale difference. In reality, one long call may control more or less stock than the arbitrary $100,000 initial account value and is not germane to this discussion.

With that resolved, I now feel comfortable to show this:

The greater stability of the long call (blue line) is seen in terms of a higher low and subsequent lower high. Aside from that, I think the table presented last time did more to illuminate differences.

What we really don’t see, which I continue to contemplate as a potential game changer, is the peace of mind coincident with a blue line that cannot lose any more in one year than it did in 2008. I will talk more about this later.

Speaking of psychology, both curves are deceptively smooth because they only contain one data point per year. The market moves around much more than this. While sharp selloffs can impart great fear among investors, owning a long call during a 2008-like selloff may put me near a loss level beyond which I can lose no more. I am therefore freed of the temptation to exit, which for shares often locks in catastrophic losses at the worst time (see last paragraph here). By holding on at market-crash lows, the only way for the call investor to go is up.

To get a better sense of actual volatility, I backtested 24 additional days between 2007 – 2020 where the underlying market hit near-term lows:*

The total return and starting/ending points are all the same in this enhanced graph. The additional data points highlight more of the downside volatility actually experienced.

Between the long call and long shares, MAR by MDD differs less in the enhanced data set than it does in the original: 3.27:1.99 (enhanced) versus 5.30:3.02 (original).

Why is this?

Next time, I will continue with a brief excursion into the weeds.

* — The actual MDD for all 5,244 days is not captured because I did not backtest any near-term highs.

Call Me Crazy (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on June 4, 2021 at 17:48 | Last modified: May 17, 2021 16:51Last time, I presented a long call backtesting procedure. Today let’s get into some results.

I used OptionNet Explorer (ONE) to help me with the work. ONE is an excellent piece of software. At some point, I will do a complete review of ONE and compare it with OptionVue.

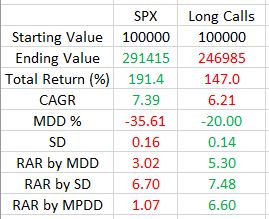

This backtest goes from Jan 3, 2007, through May 13, 2021:

SPX outperformed in terms of total return and compound annualized growth rate (CAGR): annualized return geometric mean.

All of the volatility metrics are in favor of the long call. Maximum drawdown (MDD) is 43% lower for the long call. While it’s bad practice to take a percentage of a percentage (see fourth paragraph here), risk-adjusted return (RAR) by MDD is much better for long call. As MDD is based on one occurrence (2008, in this case), I also calculated RAR by standard deviation to get a broader overview. This still favors the long call albeit only slightly.

Maximum potential DD (MPDD) is how much I can possibly lose were the market to go to zero. For a long call, this is limited as shown in the risk graph here. Until expiration, all I can lose is the amount I paid for the call. With shares, I can lose 100%.

Let’s illustrate with an example. On Jan 3, 2007, SPX traded at 1416.6 and the Dec 2009 1425 call went for $155.20. For the right to buy 100 shares of stock, then, I paid $15,520. The value of 100 shares of stock was $141,660.* Were the stock market to crash and go to zero, I would lose $15,520 owning a long call versus $141,660 owning the shares.

Not a perfect analogy (by any stretch), but a long call is like “paying rent” to participate in stock returns where the most I can lose is the rent itself. If the house is destroyed, then I do not lose the value of the house. If the stock market goes to zero, then I do not lose the total value of the stock. With regard to ultimate risk, such deleveraging may be a game changer. This is why the 60/40 stock-bonds portfolio has long been championed as a diversified portfolio by the financial industry.

I think deleveraging should somehow be factored into RAR because deleveraging lets people sleep well at night (I discussed importance of RAR in the fifth paragraph here). Here, RAR by MPDD is six times better for the long call than underlying stock.

More caveats to be considered next time.

* — SPX cannot be purchased directly. The SPY ETF would suffice, and since its price is 1/10

that of the index, 100 * 10 = 1000 shares could be used as a proxy.

Call Me Crazy (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on June 1, 2021 at 06:34 | Last modified: May 17, 2021 10:52In these two posts, I started to introduce components I am considering for a new portfolio investment approach. In this post, I will present a long call backtesting approach.

In my opinion, the long call risk graph has one very attractive potential feature: built-in insurance. I included the risk graph in Part 1 (linked above). Notice the horizontal line that extends leftward to zero. That represents a range of prices for the underlying where PnL at expiration does not change. Although I won’t discuss it any further here, this feature makes the long call a prime candidate for “cash replacement.”

When position sized properly, the long call acts like insurance because the premium I pay up front is the most I can lose until expiration. What I need to thoroughly understand is annual cost as a percentage of the underlying. The cost drags down total return, which is bad. The good thing is that I should feel completely safe in case the market goes down. Good, good, good—this is my main reason for being here today.

To gain more understanding of long calls, I conducted a backtest as follows:

- On first trading day of year, BTO the first OTM call with expiration in December two years hence.

- If underlying falls within a couple points of a strike price, then buy ATM option instead.

- Include $1.00 per contract for commission.

- Factor in [aggressive] slippage by selecting price 20% of the way between natural and mark.

- On first trading day of next year, STC the long call.

- BTO a new long call as described above.

Data columns included:

- Date and DTE

- Underlying price strike

- Round trip commission

- Mark and actual prices for open and close

- Current cost

- Maximum ($) potential loss

- Maximum (%) potential drawdown (MPDD) for account and underlying

- Account and underlying annual ROI

Initial metrics to compute included:

- Cumulative return

- Geometric mean

- Annualized return

- Standard deviation (SD)

- Maximum drawdown (MDD)

- Risk-adjusted return by SD, by MDD, and by MPDD

I will present results next time.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (0) | Permalink