Backtesting Issues in ONE (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on May 27, 2021 at 06:33 | Last modified: May 26, 2021 15:27Last time, I delved deeper into some crazy-looking data I have seen in OptionNet Explorer (ONE) and why it makes little sense. Today I will finish up.

One thing I wonder is whether part of this has to do with inaccurate quotes approaching the close. For example, on 5/7/21 at 3:55 PM EDT, SPX was ~4231. With 7 DTE, the 4275 put (OI = 22) is listed at 46.60 / 54.40. At $7.80, that is wide enough to drive the proverbial truck through! Another trader said:

> I don’t know what BD you use, but the SPX bid/ask spread on an option

> 7 DTE with Fidelity is seldom greater than $2—usually between $1 – $2.

This was puzzling because I see wide spreads like this often in ONE. I backed up to 3:30 PM and with SPX ~4236 (OI still 22), the same 4275 put shows 48.40 / 49.00. What an enormous difference! I would trade the latter all day long. With the former, I’d be concerned that slippage might completely offset my edge.

I have heard many times that bid/ask spreads frequently widen after the close rendering EOD quotes unreliable. Could this apply to 3:55 PM? I would actually think this would be smack dab in the busiest, most liquid part of the trading session when bid/ask spreads are narrowest and quotes are most accurate.

EOD liquidity may also pertain to quote freshness. I’m not talking about Sara Lee bread here, but rather how recently the option last traded. An option that has not traded for days (if ever) will likely show a stale quote. Quotes from liquid times of the day are less likely to be stale because higher-volume trading is taking place, but this is a probability: not a guarantee. In the example above, constant OI (22) suggests the option may not have been traded [between 3:30 and 3:55 PM], which then begs my question why the spread would be jacked wide open 25 minutes hence.

I will not backtest with quotes that violate strike arbitrage. I simply cannot believe I would actually see those numbers in real-time despite ONE Customer Support claiming this to be the case [and if I did, then I should immediately arb it regardless of what my current strategy calls for]. Even if I could salvage the exorbitant bid/ask spreads seen on ONE by moving the whole quote up or down to get a valid option chain, it would require spreadsheet manipulation and be a hassle to do.

Open Interest (OI) may be germane to this discussion. OI is 22 in the example given above. This is relatively high compared to what I see on the DITM puts in 2007-2009, which often have slim to no OI. This makes me wonder about a couple things. First, with such low OI am I seeing stale quotes that would change markedly were I to actually place an order? Second, is low OI a real cause of larger slippage? Given ONE data, round-trip slippage for ~5% ITM SPX naked puts in 2007 averages just over $1.30. With slippage factored in, maybe the sticky extrinsic no longer violates strike arbitrage.*

One final consideration regards a methodological tweak I applied in backtesting before Weeklys became available. These particular trade guidelines called for selling 1% ITM with 7 DTE. Before Weeklys, I sold 4-5% ITM on options 4-5 weeks to expiration. The former may be much more liquid than the latter for two reasons. First, near-dated options are usually more liquid than far-dated. Second, expected move is not directly proportional as applied here but rather proportional to the square root of time. Relatively speaking, I was therefore using options even deeper ITM.

I may not be able to backtest with these quirky option prices at least until I have more experience trading similar options to know what usual slippage and bid/ask spreads are like. For now, I should trade small and consider starting my backtest later in the data set when quotes are more reliable. Once I have gained a familiarity with these particular options, I can apply what I know to correct any seemingly distorted quotes from ONE.

* — This would not be the case if bid/ask spread is also similar across a range of strikes.

Backtesting Issues in ONE (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on May 24, 2021 at 07:55 | Last modified: May 13, 2021 10:53Last time, I presented some screenshots detailing quirky things I have been seeing in OptionNet Explorer (ONE) pertaining to data. Today I will continue the discussion.

My initial thought was that I should not be seeing zero extrinsic value across a range of strikes with significant time to expiration. If the benefits of early put exercise (i.e. earning risk-free rate on the proceeds) outweighs the extrinsic value, then the put should be exercised early. Since extrinsic value is surrendered upon exercise, put buyers can exercise ITM options without penalty once extrinsic value is gone. They can then implement the proceeds elsewhere.

If what I am seeing in ONE were accurate, then early exercise should be common. Based on my experience and what I hear from others, it is not.

Wait! I now realize I made a major oversight here. Looking back at the screenshots, do you see it?*

The more general case of seeing constant (“sticky”) nonzero extrinsic value across a wide range of strikes also seems wrong.

I e-mailed ONE Support on this issue and got some meaningful information. I strongly praise DJ who has been very helpful and usually prompt with his response time. He writes:

> The data isn’t corrupt but you will notice wider spreads on some

> instruments, particularly SPX when using EOD quotes. These were

> the exact quotes provided by CBOE so they are accurate and exactly

> what you would have seen in the market at that point in time when

> viewed at the EOD…

>

> I note what you refer to as the “sticky” nature of some of the

> quotes but again, they are correctly derived from the market data.

> Our beta version shows both bid and ask prices (as well as mid

> price), and you will notice up to $3 spreads on some strikes at

> the EOD. This can inevitably impact the calculation of both IV and

> extrinsic value, depending on where the mid price resides and

> how the spread widens.

Provided we believe DJ, which I do, the data seen in ONE are accurate.

I remain troubled because these inconsistencies seem to violate option arbitrage. As an example with the underlying at 100, suppose the 105 and 110 puts are priced at $5 and $10, respectively: both having zero extrinsic value. I could then sell the credit spread for $5 and have a position that would at worst lose nothing (options expire ITM) and at best profit $5 (options expire worthless). This edge would be exploited repeatedly until it went away (selling causes extrinsic value to decrease while buying causes extrinsic value to increase).

A range of options having constant nonzero extrinsic value should similarly violate option arbitrage. With the underlying at 100, suppose the 105 and 110 puts are priced at $8 and $13, respectively: both having $3 extrinsic value. I could then sell the spread and have a max potential profit of $5 (options expire OTM) with a max potential loss of breakeven (options expire ITM). Again, this edge would be exploited repeatedly until it disappeared.

I question whether flawed numbers like this can be used to backtest, and I remain puzzled as to why I am seeing it.

I will continue next time.

* — SPX has cash-settled, European options that are not subject to early exercise.

Backtesting Issues in ONE (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on May 21, 2021 at 07:16 | Last modified: June 20, 2021 08:51I recently subscribed to OptionNET Explorer (ONE). ONE is option analytics software that has been around for many years. I have started my ONE backtesting journey with ITM puts and have run into questions about data integrity.

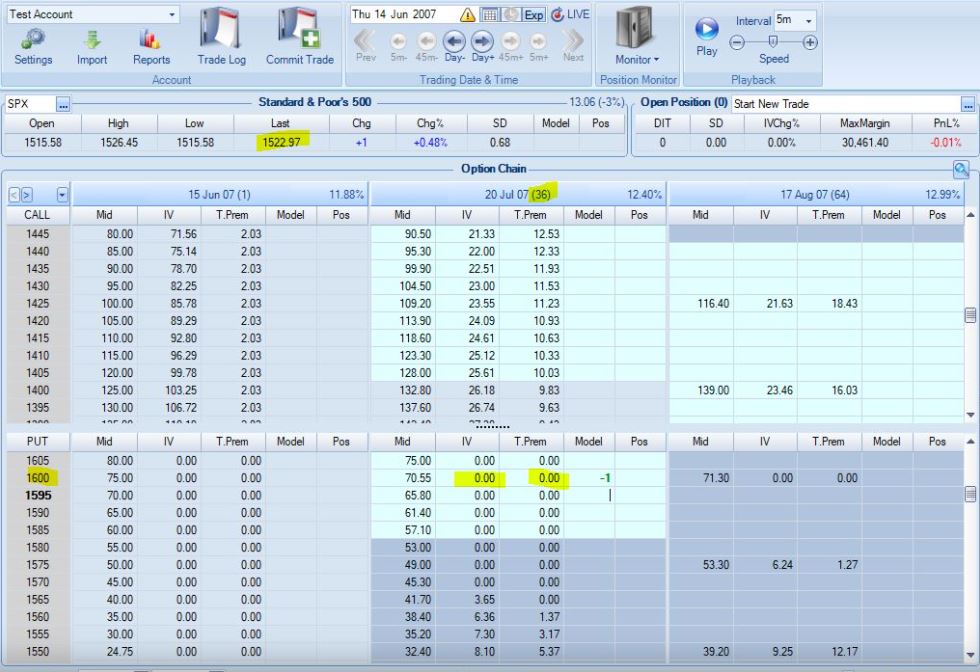

I started backtesting in 2007. Look at the following screenshot:

The underlying is at 1522.97. I highlighted the 1600 strike, which is roughly 1% ITM/week compounded geometrically. Zero extrinsic value (T.Prem column) is displayed. In fact, a range of strikes show zero extrinsic value down to the 1565 strike. With five weeks to expiration, this doesn’t feel right to me even being DITM.

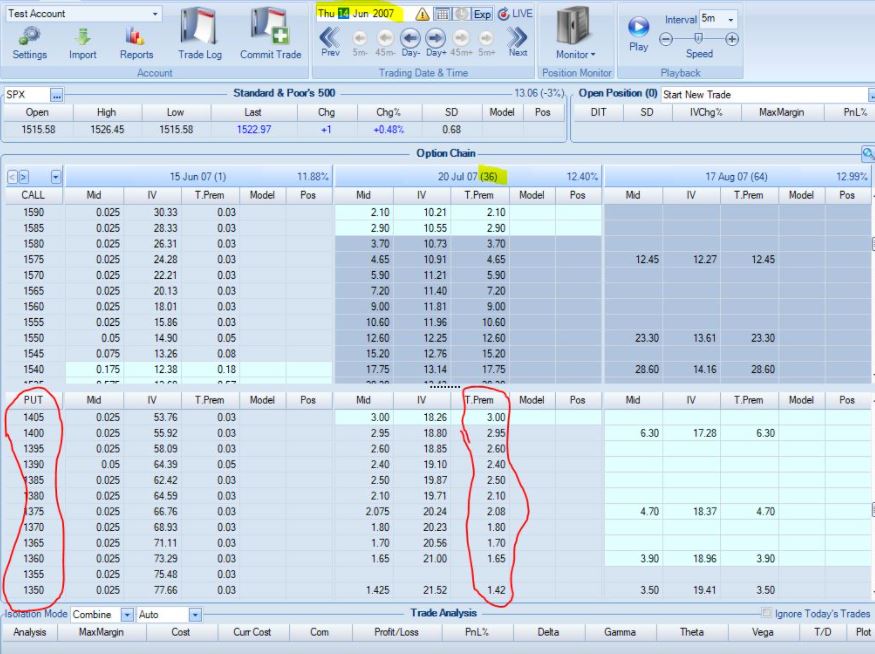

Look at the OTM portion of the option chain:

These puts have extrinsic value well into the third standard deviation. Vertical volatility skew would dictate OTM puts to have a higher implied volatility (more extrinsic value) than calls OTM by the same amount (referred to as moneyness). I believe this also pertains to ITM vs. OTM puts. Assuming this to be true (especially so if not), I still question what we’re seeing here. The option chain shows DOTM puts with extrinsic value well beyond the second standard deviation compared to ITM puts with zero extrinsic value less than a full standard deviation out.

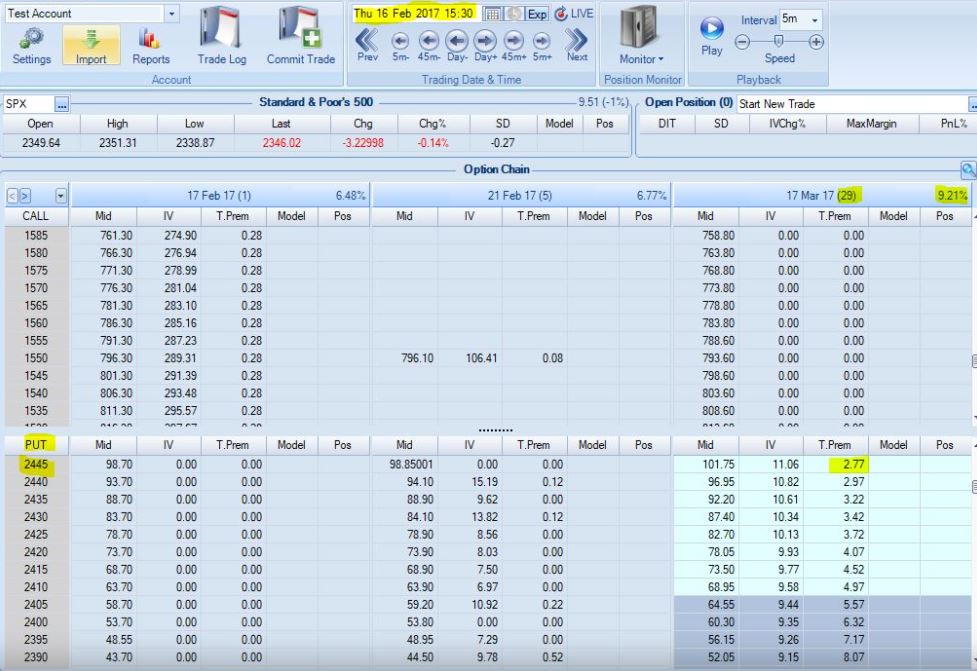

The following screenshot feels about right to me:

Extrinsic value should be greatest ATM and proportionally decline with moneyness. Whether the relationship is like an inverse V or a bell curve, what we see here seems much more reasonable. We shouldn’t see all zeroes.

I used to use OptionVue and I would sometimes have similar issues with their data. It didn’t seem to be every day, certainly, but before 2008-2009 or so, it was somewhat prevalent.

I will continue next time.

* — One standard deviation equals underlying price * implied volatility (decimal) * SQRT ( DTE / 365)

Brokerage Perspective on Freeriding vs. Good Faith Funding Violations

Posted by Mark on May 18, 2021 at 07:20 | Last modified: April 23, 2021 10:37Today I will discuss freeriding and good faith funding violations.

I contacted TD Ameritrade (TDA) about the specific example described at the end of my last post and they said it would not be an issue. I would receive an e-mail over the weekend telling me the shares had been assigned and that I need to take immediate action to cover the position. I am clear provided I do this near the open on Monday morning. If I delay, then TDA has the right to apply discretion on a case-by-case basis. In so doing, they will make every effort to do what’s best for my account value and the brokerage.

Before I explain the brokerage perspective, I want to reference the SEC website with regard to “freeriding.” According to the SEC website, I am allowed to use unsettled funds to make a subsequent transaction in a cash account but I must wait until the initial funds settle before offsetting the subsequent transaction. Failure to do so is called freeriding. Covering the short with $191,000 of unsettled funds (recall that the account previously contained $100,000) is okay but continuing to trade with those funds before the $291,000 settles is not.

Freeriding is a violation of the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation T, and brokers/dealers must suspend or restrict cash accounts for 90 days as a penalty. This shouldn’t be an issue with margin accounts because the funds may be borrowed until settlement clears. If a cash account is restricted, then securities may only be purchased using settled funds. Equity (option) transactions are settled two (one) business day after the transaction date.

TD Ameritrade makes a distinction between freeriding and a good faith violation. Here is an example of the latter:

- On Monday, I hold ABC stock.

- On Tuesday I sell ABC stock, which will settle on Thursday (two business days later).

- On Wednesday morning, I buy XYZ stock.

- On Wednesday afternoon, I sell XYZ stock for a profit.

My Wednesday morning purchase was done on good faith that the sale of ABC would settle thereby making the funds available. I am in violation because I did not wait for the ABC settlement before selling XYZ stock, which means I never fully paid for XYZ. For this, I would receive an e-mail explaining the violation. If I am in violation three times within 12 months, then my account will be restricted to using only settled funds for 90 days.

TDA regards freeriding as a situation where funds are never in the account. An example of this could involve a failed incoming ACH transfer. While ACH transactions may take up to two business days to settle, TDA makes the funds available immediately for marginable stock above $5 on a listed exchange (not options). Suppose that on the day I open a new account with a $25,000 ACH transfer, I buy $25,000 of QRS stock and sell later that afternoon for a 100% profit. If the $25,000 deposit never goes through, then I have committed a freeriding violation and profits will be seized.

In speaking with TDA, my confusion between freeriding and a good faith violation may be explained by limited margin they grant to retirement accounts. Margin is pledging securities as collateral for a brokerage loan. Accounts given tax-deferred (traditional IRA) or tax-exempt (Roth IRA) status are prohibited from accepting such loans and may lose their favorable tax status for doing so. The limited margin applied here is the ability to use unsettled funds for subsequent trades—not to provide leverage, but rather to prevent trip-ups resulting from specific, temporal oversights.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkPotential Tax Implications and Settlement Issues

Posted by Mark on May 13, 2021 at 06:54 | Last modified: April 23, 2021 10:14Before I go into the second part of this investment approach, I want to address tax considerations and discuss some details about option assignment and settlement.

Please keep in mind the following disclaimer: I am not a tax professional and while the following holds true for me, your personal situation may differ.

If a long-term long call is substituted for the married put, then favorable tax treatment may be available if done with cash-settled SPX options rather than SPY. The underlying index (SPX) cannot be purchased, so the synthetic equivalent must be used in lieu of the married put. I have read—but not confirmed—that some brokerages allow for cross-margining between SPY shares and SPX options. I wonder if said brokerages would cross-margin with other S&P 500 ETFs as well (e.g. IVV)?

Because I am not a tax specialist, I will quickly go over tax implications even though this deserves much more space. Options held longer than one year qualify for long-term capital gains (LTCG) treatment. The SPY ETF qualifies for LTCG treatment if held for more than one year (with the goal being to presumably hold and defer tax payment indefinitely). As suggested above, “favorable” means profit/loss on SPX options gets split into 60% LTCG and 40% short-term capital gains regardless of holding period. Holding for longer than one year would be ill-advised because I would still have to pay 40% short-term capital gains taxes on what would otherwise qualify as 100% LTCG (e.g. SPY options).

Assignment of shares can be a problem for retirement accounts. Consider what happens if I sell 10 Jul 300/290 bear call spreads on SPY for $3.00 each in my $100,000 IRA account. The most I can lose appears to be 10 * $100/contract * 10 contracts = $10,000, which is 10% of the initial account value. At expiration, suppose SPY trades at $291. I will be assigned on the short 290 calls forcing me to sell 1000 shares for $290,000. Because short positions are not allowed in IRAs, the position must be covered immediately. At Monday’s open, suppose I buy to cover for $291/share (assuming no price change from the close, which is not very realistic). I lose $1,000 of the $3,000 initially credited at trade inception on the assignment/cover, bank the profit, and move on.

“Not so fast, my friend.”

Being assigned on the short 290 calls brings 290 * $100/contract * 10 contracts = $290,000 into my account, but trades are not settled until two business days after execution. Being an IRA account, I must cover the short immediately with $291,000, which I do not have currently available since the sale has not yet settled.

Is this a problem?

I will discuss next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkNot Exactly a Cash Replacement Strategy (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on May 10, 2021 at 07:06 | Last modified: April 20, 2021 09:49Today I continue study of what I am calling not exactly a cash-replacement strategy: the first component of a new (to me) investing approach.

This component is not exactly a cash-replacement strategy because it carries more risk than cash, which can really only lose to inflation. Backtesting will help to put context around “more risk,” but max loss being realized over a string of consecutive years would severely damage core equity. If I deem the potential for adverse performance to be limited, then I may choose to use this as a cash replacement.

I can think of a few potential variants with the first being leveraging up leftover cash. In the example I gave last time, on a $247 investment my max risk is less than $20 (not counting dividends) for the year. Why not double to 200 shares and buy two puts? My max risk would then be less than $40, which is just under 17%, and my potential profit (unlimited) would increase twice as fast. The downside is that losses start to accrue with anything less than a $20 (per 100 shares) gain by expiration.* I am interested to look at the historical distribution of returns to get an idea of the probabilities.

A second potential variant to the married put cash replacement is resetting the long put ATM to lock in gains once the market rallies X%. This would cost more money although if months have passed, then I can seize the opportunity to roll the put out in time, which would eventually have to be done anyway.* I think backtesting this entire approach will have to be some sort of horizontal (by date) summation of components. For this variant, separate backtesting of the put involves exit after an X% gain in the underlying (for a loss) or exit with Y months to expiration (for a gain or loss): whichever comes first.

A third variant to the married put cash replacement is to buy a put debit spread for limited downside protection if VIX > Z. This would limit cost of insurance at the risk of losing more overall if the market decline continues thereby forcing an early exit (e.g. at the long strike?). From a backtesting perspective, this would be challenging because not only do I have to backtest across a range of Z, I should also backtest across a range of vertical spread widths (or debit spread prices).

A married put is synthetically equivalent to a long call, which suggests as a fourth variant purchase of a long-dated ATM call alone. With one leg instead of two, this might be an easier trade (unless I were to hold SPY shares and only move around the long put, which would nullify the simplicity advantage). Done this way, I should invest the remainder in T-bills or some other cash proxy unless I intend to leverage up as described three paragraphs above.

I will continue next time.

* — My intent will not be to hold to expiration due to accelerated time decay in the final months.

Not Exactly a Cash Replacement Strategy (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on May 7, 2021 at 06:53 | Last modified: April 19, 2021 17:18Today I will talk about the first component to a hedged approach to option trading.

A cash replacement is relatively safe. Cash is savings accounts, money market accounts, certificates of deposit, FDIC insured, etc. Cash suffers from inflation risk: it will be devalued over time if the interest rate (currently near zero) is less than the rate of inflation, which is generally not the case (see below). A cash replacement will not be government insured, but it should have comparable risk in terms of how much it may lose in any given year.

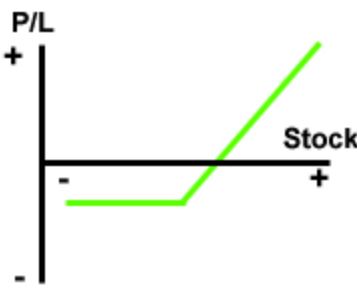

The first component in the proposed hedged portfolio approach is a married put. This is a long-term ATM put and 100 shares of underlying stock. The maximum potential loss is the total cost of the put. If the market is lower at expiration, then the loss incurred by the shares is offset by intrinsic value of the long put. If the market is higher at expiration, then the cost of the put subtracts from gains in the shares. The risk graph is shown below:

Before I can assess a potential cash replacement, I need to understand the historical annualized return on cash. According to Portfolio Visualizer, using Vanguard Short-Term Treasury Fund Investor Shares (VFISX) as a proxy for cash reveals an average CAGR of 3.75% (1.48% after inflation) from Jan 1992 through Mar 2021. The range is -0.57% to 12.11% with a standard deviation of 1.91%.*

Next, I need to run a backtest to get a comparable performance distribution for the married put. The shares will benefit from the annual dividend to discount the put cost, which is ~2% in recent decades.

Always implied when we see benchmark returns is that 100% of the account is invested. Few people really do that. The long-time rule of thumb, which I am not advocating, has been to invest in equities a percentage equal to “100 minus your age.” In a pinch, a “conservative” asset allocation often preached is 60% stocks + 40% bonds. Either way, whatever the equities return in any given period must be diluted accordingly to calculate total portfolio return.

If I believe the married put to be sufficiently safe, then I can use it as a repository for cash in the account and avoid deleveraging the portfolio as just described. Committing 100% of my investible assets to an approach like this would immediately give me a 4% (or more) advantage per 10% CAGR according to the traditional approaches mentioned above. That’s a huge head start.

While I will be interested to see the overall return of the married put, in theory the total cost seems more reasonable in periods of low volatility than high. In the latter portion of 2017 with SPY around $247, a 2-year ATM put could be purchased for about $20. The dividend yield was about 2% so the annual cost of this insurance was about 2.1% (rounding up).

Would I risk putting my remaining assets in a vehicle that could lose no more than 2.1%? Inflation has averaged 1.2% over the last 12 months, which means cash has returned roughly -1.0%. Losing 1% is not much better than losing 2.1%, perhaps, although with implied volatility currently higher maybe the potential loss is also higher—either way, if my answer is ultimately yes then this could adequately serve the purpose of cash replacement.

I will continue next time.

* — As an aside, correlation to US equities is -0.19.

The Road Forward

Posted by Mark on May 4, 2021 at 07:20 | Last modified: April 19, 2021 08:33I am at an inflection point. Time to take a step back, review where I’ve been, and more clearly define where I am going.

I haven’t been happy with my downside risk after 2018 when, for all practical purposes, I lost money for the first year since switching to full-time trading in 2008.

Initially, I thought the way around this was migration to a portfolio of diversified asset classes. I found Following the Trend by Andreas Clenow (2013) to be quite the eye-opener.

I then thought I should learn some Python to backtest some noncorrelated futures markets to validate Clenow’s book (especially because of this comment).

In between, I took a course on algorithmic trading and spent several months trying to develop my own trading system. Some of this time included use of a genetic algorithm. Although the total number of strategies I tested amounts to a proverbial “drop in the bucket,” none of this worked.

I spent a minute trying to build a futures backtester in Python. I wasn’t encouraged by the speed of my program and I wasn’t sure how to proceed coding the trading rules. Although I did not expend great effort in searching, I was not able to find a project collaborator.

Late February through March 10, 2021, I contemplated preparation for CFA Level I. I had several contacts with the CFA Institute and board members of the local CFA societies. As it turns out, my trading experience does not qualify me for CFA Charter because I haven’t been working in the industry proper. I could still take (and hopefully pass) the exams, but in order to become an official charterholder I would have to work 4,000 hours over at least three years at a financial firm.

Because of the low pass rates, I believe passing the exams would get me in the door with many prospective employers. Even without the charter, anyone who talks to me about what I have been doing since 2008 will quickly find out that I have learned a great deal about trading and investing over the 13+ years (regardless of how well I have performed doing it, which is another discussion altogether).

I decided not to begin preparation for the CFA exam and since making that decision, I have caught up on my 18-month backlog of financial publications.

Most recently, I have done some intense reading and studying of the writings of KR: an online investment contributor. This individual has been very generous writing many articles and answering questions about his approach, which hedges downside risk, for free. His is really a compilation of trading strategies that would best be served by backtesting each strategy independently and, if I could nail down allocation for each component, computing a weighted average of % PnL by date. This assumes I can get daily performance exported to .csv, which is not a trivial matter. The backtester I’d like to try for $39/month cannot do this.

Over the next few posts, I will start slow by discussing some of KR’s content.

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | Permalink