The Lemming Effect (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on February 29, 2016 at 06:34 | Last modified: January 22, 2016 08:39Today I want to address two questions that come to mind about the Lemming Effect.

First, what established said trader as a sought-after authority? In fields like medicine, law, or education, regarded experts have diplomas, documented work experience, patents, sometimes high-profile clients, published manuscripts or books, etc. In finance it seems to be more about simple persuasion, which comes with a tailwind given the promise of making money. This is what underlies the Lemming Effect. People saw trades listed in a spreadsheet and never mind whether they were real, to the lemming brain that was enough to crown him “genius.”

Unfortunately in trading, strategies can work for a long period of time until they don’t and catastrophic loss is incurred. Traders get blinded to this by the greed inherent in making lots of money. This is precisely why I believe it is important we do our own work using a complete system development methodology.

The second question I wonder about is what are people hoping to gain by studying that trading log? Without taking a survey I really don’t know. I know it can’t help me and therefore I don’t look at it. This makes me think others are heading down the wrong path since they are rushing to look at it.

I briefly communicated with one member of the group about the Lemming Effect and he totally agreed. He did say something interesting in their defense. He would read a 400-page trading book with the expectation that 99.9% would be useless. If even one tidbit positively influences him in the future, though, then the read would be worthwhile.

That sounds like a huge investment of time for very little, if any, potential return. Is there no better way?

Categories: Trader Ego | Comments (0) | PermalinkThe Lemming Effect (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on February 25, 2016 at 07:20 | Last modified: January 22, 2016 07:11Google defines lemming as “a person who unthinkingly joins a mass movement, especially a headlong rush to destruction.” Coincidentally, the example it gives is “the flailings of the lemmings on Wall Street.”

I have found finance to be a curious endeavor because unlike other disciplines where educational degrees or verifiable experience are regarded to establish credibility, financial credibility is more about being outspoken and visible to others.

I belong to a trading mailing list where some members post their trades every day. They occasionally give some commentary about these trades to help explain the strategy.

Recently, one of the members posted his trading log to the list. He wrote that he would be happy to send this log to anyone who provided him with an e-mail address. Over the next two weeks, I am not exaggerating when I say tens upon hundreds of people I had never seen post before responded with “can I get a copy? Thanks!”

I could speculate and say in the absence of anything, maybe people look to others for a starting point. Unfortunately no Holy Grail exists and even seeing what works for someone else is not necessarily going to work for them. It takes a lot of hard work to develop a personal strategy that will work consistently over the long-term and that work does not include copying others. No free lunch exists. One way or another, the hard work must be done.

Despite my speculation about why, the phenomenon seems quite repeatable. Over the years I have associated with many other traders and participated in many trading groups. Whenever beginners get so much as the tiniest whiff of something that could potentially make them money, they appear to trip over each other to get it no matter how meaningless it might be. This is the Lemming Effect.

Categories: Trader Ego | Comments (2) | PermalinkOn Discretionary Trading (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on February 23, 2016 at 07:23 | Last modified: January 20, 2016 10:47I mentioned previously what recently got me thinking about discretionary trading.

I believe discretionary trading to be something between the pot of gold on the other side of the rainbow and a salesperson’s best friend for life. While markets may not be completely random or predictable, we can test an idea on all the data available to us and then imagine a drawdown worse than anything seen historically. The inability to quantify this hypothetical future drawdown may be the only source of unknown risk from a valid system development methodology.

Discretionary trading involves lots of unknown risk that falls in the “don’t know what you don’t know” category. People seem to be easily convinced that discretionary guidelines are a plausible way to learn profitable trading. In reality, discretionary trading is highly susceptible to heuristic thinking, cognitive bias, and logical fallacy. Unlike discretionary traders, experienced system developers take exhaustive steps to avoid things like the confirmation bias, the fallacy of affirming the consequent, the fallacy of the well-chosen example, insufficient sample size, and curve-fitting.

I cannot prove that discretionary trading does not work but I have seen two clear-cut phenomena. First, profitable trading strategies in select communities are all the rage until they stop working by which point other strategies have become the focus. Second, many popular, outspoken traders disappear from public view over time. Did they get bored and stop trading? Did they switch communities like snake oil salesmen moving to the next town? Did they strike it rich from trading and retire? Did they suffer catastrophic loss and go quietly into the night?

When catastrophic losses occur, excessive position sizing can always be blamed instead of discretionary trading itself. To those who insist on keeping position size small I always raise the issue of how one can possibly generate requisite profits to cover the monthly living expenses. “Trade small” is theoretically invincible as a strategy to avoid Ruin but whether it can practically work for anyone is a very individualistic matter that is rarely addressed in public.

Hobby/part-time traders never hoping to do so as a business can probably trade discretionarily in small size with impunity.

Categories: System Development | Comments (2) | PermalinkOn Discretionary Trading (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on February 19, 2016 at 06:52 | Last modified: January 22, 2016 10:12I suspect these are not going to be new thoughts on discretionary trading but they are the first I’ve had in a while.

I feel my approach is more unique than my trading strategies. The former is based on system development whereas the latter can be found in trading books anywhere.

Despite going through the 15-year database twice, I am not done with naked puts. I have a large sample of trades and historical context for expected returns in good times and in bad. Much data analysis remains to determine whether any hidden edges exist but I’m happy with the conceptual framework developed thus far.

We had a good trading group meeting the other night where two new strategy variants were discussed. When it comes to discussing a trade or strategy, my mind immediately goes to system development. Is it something that can be operationally defined? If not then where are the holes? How much of a pipe dream are we actually considering?

After naked puts, a butterfly trade is the next place I would like to channel my efforts. I’ve given this some thought and had trouble defining the strategy in simple and limited steps. I generally find too many degrees of freedom for a systematic approach. Perhaps this is more suited as a discretionary trade with loose, general guidelines.

The problem is that I remain very skeptical about discretionary trading. Some of my old ideas may be read here, here, and here. In the next post I will start to describe my current philosophy.

Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkMean-Reversion Study (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on February 16, 2016 at 07:28 | Last modified: December 8, 2015 07:58The last two posts have detailed a mean-reversion study I did by making use of a price oscillator. Today I want to wrap up with some discussion.

As I pointed out, I would not conclude mean reversion from these data. If it’s mean-reverting in one direction and trend-following in the other then something else is taking place. The simplest answer seems to be volatility.

I would also make a couple observations to satisfy the curve-fitting crowd. I used 23 as the period for Osc, for MFE, and for MAE. To ensure what I saw here was not fluke, I should repeat the study for other periods (e.g. 25, 21, 27, 19, 29, 17, etc.). Similarly, I arbitrarily divided the data into 20 groups. I think it would be useful to divide into 10 groups, five, and maybe four to see if the observations are consistent. If they are then we have something. If not then it’s chaos.

Finally, given that most data were clustered around the extremes of Osc, it is tempting to use only the highest and lowest groups for the analysis. With 20 groups this is 36% of the data. With 10 or four groups this would be 44% or 68% of the data, respectively.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (0) | PermalinkMean-Reversion Study (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on February 12, 2016 at 06:06 | Last modified: June 1, 2017 13:41Last time I described the methodology for a mean reversion study. Today I will discuss results.

The data for this study span Feb 2001 through Oct 2015.

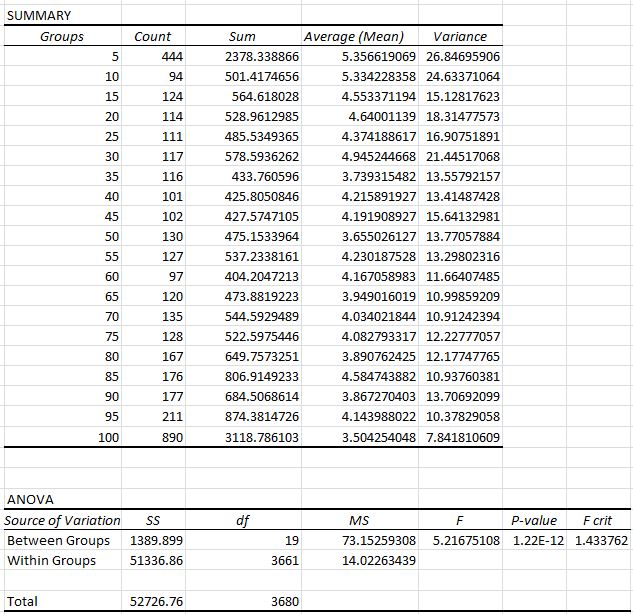

Here are the ANOVA results for MFE:

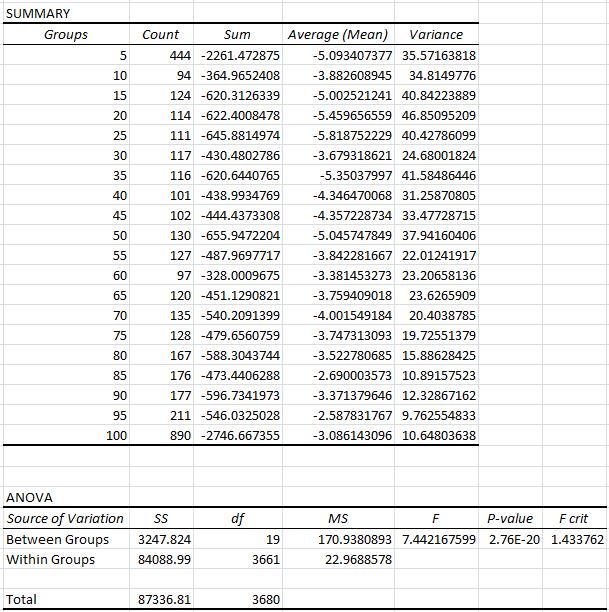

Here are the ANOVA results for MAE:

The first thing I noticed were the F-values > 5 and > 7 along with the corresponding p-values on the order of 10-12 and 10-20. Based on what experience I have in scientific research those numbers are extreme. This is probably to be expected with a large sample size (n = 3681). This tells us the averages across groups are statistically significant. Further testing would be required to determine where the differences lie, however. Some averages may differ while others may not.

Next, look at the “Count” column. The values are going to be the same for MFE and MAE because they come from the same data set. I was surprised to see the highest values at the extremes: 444 days printed an Osc reading < 5 and 890 days printed Osc > 95. This is 36% of the data in 10% of the groups. We could say this is why the market is often characterized as “taking the escalator” on the way up and “jumping out the window” on the way down: the ascent is long and gradual while the decline is often short and sharp.

Finally, the trend of both MFE and MAE values seems to decrease in magnitude as the market goes from oversold to overbought. More specifically, MFE is greatest when oversold and least when overbought. This suggests mean reversion. MAE, however, is most negative when oversold and least negative when overbought. This suggests trend-following. Taken together, we could just say the market is most volatile to the upside and downside when it is oversold and least volatile when overbought.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (1) | PermalinkMean-Reversion Study (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on February 9, 2016 at 04:52 | Last modified: December 8, 2015 07:58Conventional trading wisdom often suggests to “sell when the market is high and buy when the market is low.” This study is designed to see if the data support such mean-reversion activity.

If I were better versed in AmiBroker Formula Language (AFL) then I could code a simple trading system and study the performance metrics. I could look at profit factor, Sharpe ratio, % winners, MDD/CAR, etc.

Unfortunately, I remain weak in that area so I turned to the old standby: MS Excel. My plan is to use inferential statistics rather than a trading system development approach.

The study methodology is as follows:

1. Start by downloading historical price information from Yahoo!

2. Create a 23-day price oscillator. The formula for this is: Osc = 100 * (C – MIN ) / (MAX – MIN)

C = current day’s closing price

MIN = lowest closing price of last 23 trading days (including C)

MAX = highest closing price of last 23 trading days (including C)

3. Create “MFE [maximum favorable excursion] next 23 trading days” with this formula: MFE = 100 * (MAX – C) / C

MAX = highest closing price of next 23 trading days (not including C)

4. Create “MAE [maximum adverse excursion] next 23 trading days” with this formula: MAE = 100 * (MIN – C) / C

MIN = lowest closing price of next 23 trading days (not including C)

5. Divide the data by Osc score into 20 groups: Osc < 5, 5 < Osc < 10, 10 < Osc < 15… 90 < Osc < 95, Osc < 100.

6. Run a single factor ANOVA to see if MFE values varied across the 20 groups.

7. Repeat for MAE values.

Will MFE and MAE differ with respect to Osc? Mean reversion would suggest that when Osc is more overbought with values toward 100, MFE and MAE values should be lower. In the other direction, mean reversion would suggest that when Osc is more oversold with values toward 0, MFE and MAE values should be higher.

I will discuss the results next time.

Categories: Backtesting | Comments (1) | PermalinkOption Trading Meetup (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on February 6, 2016 at 06:01 | Last modified: December 8, 2015 04:50As I was writing the last post I got the sense I was being too hard on this group. Today I will reality check myself.

I criticized DY for claiming to have been trading for 30 years and over seven figures per week. This is not verifiable and therefore not something I believe should be brought into the discussion. All it can do is serve as a faulty basis for trust. For this reason, I don’t share such information with others and this is probably why the organizer treated me as a newbie when answering my question.

But experience is often stated in other fields. Pharmacists will say they’ve been practicing for X number of years. Surgeons will say they have done Y number of surgeries. Lawyers will say they have litigated Z related cases [and won, which is also not verifiable]. As a society we accept these claims. Why should one not accept a similar claim from a trader?

I feel like fraud and deceit are more prevalent in Finance because it is all about the money. Pharmacy, medicine, and law may indirectly come down to money but there can also be other things involved (e.g. medical treatment, legal rights, and wanting to help others). Finance is the direct conduit to money and is therefore at risk for stronger exposure to greed: one of the seven deadly sins. While this sounds good, I have no data to support it. I should therefore recognize it as a personal bias but not act on it.

I sometimes disagree with other traders because I focus on data science while they employ “conventional wisdom.” I can continue to follow the data. If disagreement leads someone to say “I have been trading for 30 years and I trade seven figures per week” then I can respond “I have extensive live trading experience too” and move on. I don’t need to disqualify them just because they stated unverifiable experience. I also don’t need to accuse them of fraud.

Hopefully my second visit to this Meetup will be more fulfilling.

Categories: About Me, Networking | Comments (0) | PermalinkOption Trading Meetup (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on February 4, 2016 at 06:43 | Last modified: December 7, 2015 05:58I left the Meetup fuming and doubtful about my prospects of returning in January. I texted the following to a friend:

> I always find know-it-all type people at these

> Meetups who are totally full of themselves.

> Maybe I should look in the mirror and ask

> whether I am one of these too.

> I am somewhat dogmatic in my belief that so

> much of this stuff cannot be known for sure.

> Much certainty I often see displayed is

> totally unfounded.

> Perhaps that means I often butt heads with

> supposed “experts” only to raise some of the

> thought-provoking issues I believe we should

> all explore in an effort to understand this

> complicated stuff. There are many key

> concepts I still struggle with after years

> of work.

> I guess I get irritated at seeing them make

> definitive claims about things that I do not

> see as definitive. Nobody else in the group

> is going to challenge that because they are

> beginners.

DY claimed to have been trading for 30 years and over seven figures per week. I don’t care how long someone says they have been trading options or how much they claim to have made or trade because none of this is verifiable. The world of Finance strikes me as screwy because those lauded as de facto experts are usually people with significant conflicts of interest. Given the all the financial fraud perpetrated to date, I would have great difficulty trying to argue that “financial professionals” actually care more about my performance than they do getting my business, bolstering the total AUM, and making more money for themselves.

I did not enter the room with hopes of being respected as the trading expert. I hardly think of myself that way. I did not talk about my experience or about my profits (or losses). I did find it amusing/insulting that when I posed a couple discussion questions about the first instructional video we watched, the organizer herself answered with simple, incomplete answers almost as if to placate me.

Seriously?

I’ll break this down further next time.

Categories: Networking | Comments (1) | PermalinkGet a Hold of Me

Posted by Mark on February 2, 2016 at 07:03 | Last modified: February 2, 2016 07:03I don’t often hear from readers out there especially because I do not promote this blog. However, I am interested in finding a research partner. If anyone out there has a good understanding of trading system development and/or coding then please e-mail me: mark at optionfanatic.com. I’d love to hear from you!

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | Permalink