Covered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 5)

Posted by Mark on October 29, 2013 at 06:20 | Last modified: January 10, 2014 08:09In part 3 of this blog series, I discussed why CC and CSPs are less risky than outright stock. Why don’t more investors make use of them? I believe an inherent fear of options within the retail trading community has capped their use.

I have spoken with a number of stock investors over the years who have bulked at the mention of option trading.

The fact that brokerages have historically limited or disallowed option trading in retirement accounts has probably biased some traders against them.

Searching the Internet for “option myths,” I found a few articles that address the fear. Here is one:

> If you received or read a disclosure from your broker about options

> trading stating that trading options is dangerous and you may lose

> money, do not believe it. If you know what you are doing and what

> to expect from options, they can be very safe and they actually can

> be less dangerous than trading stocks themselves.

In this second article, Michael Sincere discusses it:

> Myth #1: Options are too risky

> …

> Myth #2: Options are difficult to understand

> …

> Myth #5: Options are the cause of stock market crashes

Here is a third article that also addresses the fear of trading options:

> Myth #1: Options trading is only for professional traders with

> years of experience.

> …

> Myth #3: Option trade execution is a rip-off.

> …

> Myth #5: Option trading is for older and wiser investors only.

> …

> Myth #6: Option trades are difficult to execute and should

> only be handled by professionals.

> …

> Myth #8: You have to spend thousands of dollars to get a good

> options trading education.

I would recommend reading the second and third articles in full as they cover some really good informational content.

Bottom line for today: some apprehension toward option trading and therefore toward CC/CSPs does persist. This may help to explain why more traders don’t use them.

In my next post, I will offer an opposing viewpoint.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (2) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on October 24, 2013 at 07:20 | Last modified: January 9, 2014 12:37In the last post, I argued that CCs and CSPs are less risky than owning stock outright. People are often surprised by this because some brokerages suggest otherwise.

Certain brokerages in the past did not allow CSPs or any option trading in retirement accounts. I found a number of links on-line devoted to the subject. This article from a few years ago talks about Scottrade.

This article is from 2013 and describes trading restrictions in an IRA. The article writes:

> The only universal restriction is tied to IRS rules that do not allow

> borrowing from an IRA account. This restriction blocks short

> selling, leverage using margin, and the sale of naked put or call

> options.

Since CCs and CSPs are less risky than outright stock, why should they not be allowed in retirement accounts if long stock is? They should.

This article discusses some possible reasons for the illogic.

> The higher suitability standards in an IRA makes the firm concerned

> that even though the strategy is safer than buying the stock, it’s more

> complex, and the duty to ensure that the client understands the

> risks… makes it not worth offering.

>

> The firm’s systems can’t differentiate between cash-secured put

> writing and other types of put writing that are not appropriate for

> IRAs (naked put writing, covered put writing against short stock,

> etc.)

>

> The firm’s permitted options strategies for IRAs have not been

> changed in many years. This is the most common one. Most firms

> established covered calls, or covered calls and protective puts as

> the only strategies they’d allow when they first became IRA

> custodians, and simply haven’t changed them since.

In my opinion, the tide seems to be changing as time goes by and this is good news for traders/investors. TradeKing was a holdout that did begin to allow CSP Trading in IRA accounts a couple years ago.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on October 22, 2013 at 06:03 | Last modified: January 9, 2014 11:49In this blog series, I’m detailing different aspects of the CC/CSP trade in an attempt to develop some trading guidelines for future use. Today I want to explain why a CSP is less risky than owning stock outright.

Yes a CSP, or naked put, is less risky than owning stock. Why this is counterintuitive to many is something I will discuss in a future post. The first step to understanding it is to recall that a CSP and CC are synthetically equivalent.

Saying that a CC is less risky than owning stock outright may feel more comfortable because CCs have long been touted as a “conservative [option] strategy.”

Risk management is about limiting potential loss. With a CC, I buy the stock and sell a call. Selling the call puts money in my pocket. The CC is therefore cheaper than the stock. If the stock goes to zero then I lose less money with the CC than I do the stock because I already put money in my pocket. The CC is therefore less risky than the stock because I cannot lose as much money. The CSP is also less risky than the stock for the same reason.

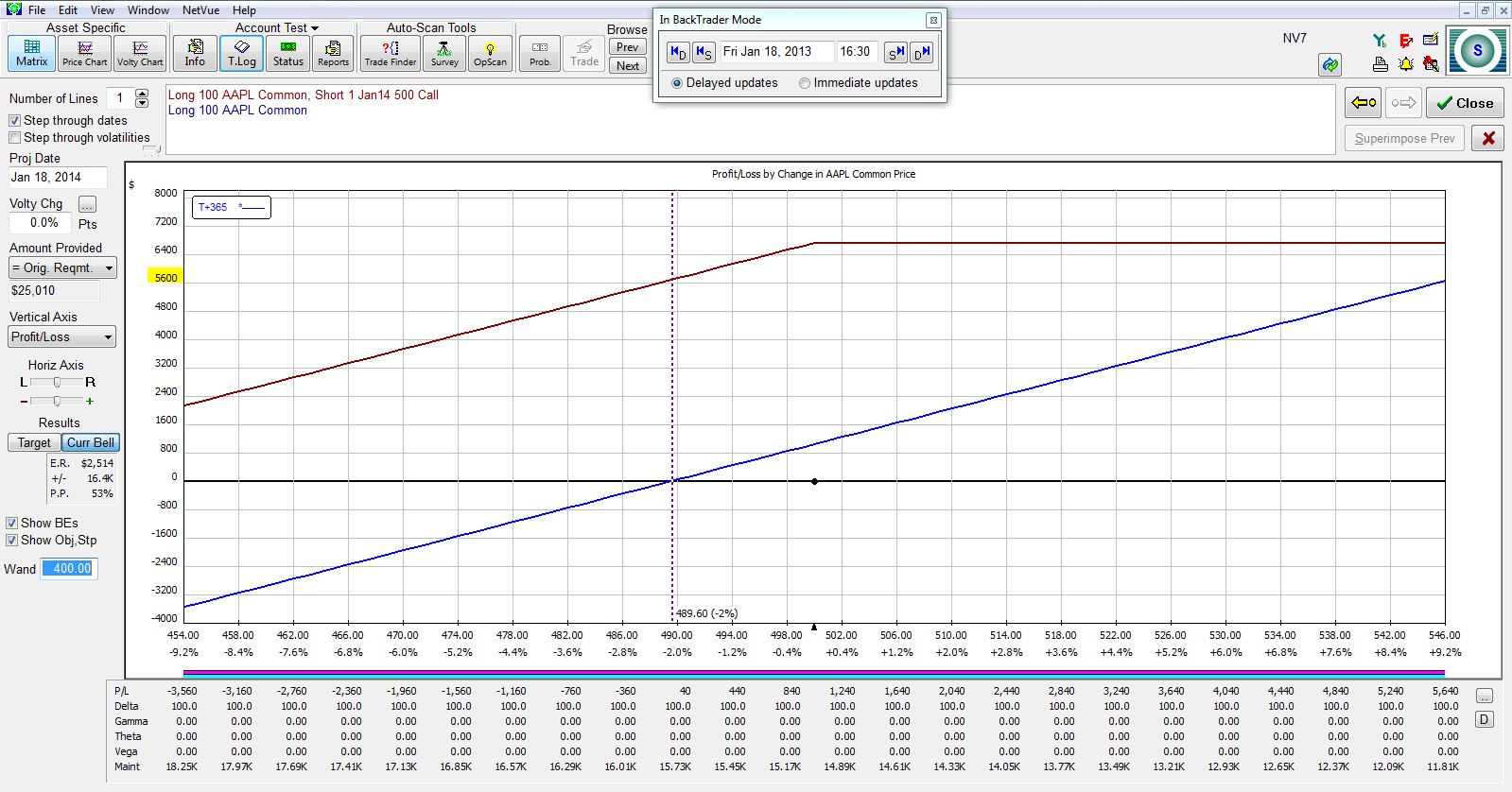

The following graph plots the PnL of AAPL stock (blue line) and CC position (purple line) 365 days after trade inception. The option expires on that day. Stock dividends ($1,040) are included:

The vertical, dotted line shows breakeven for the stock position if the stock price falls. At this zero profit level, the CC shows a profit of $5,600, which is the profit from selling the call at trade inception. The stock is more risky than the CC.

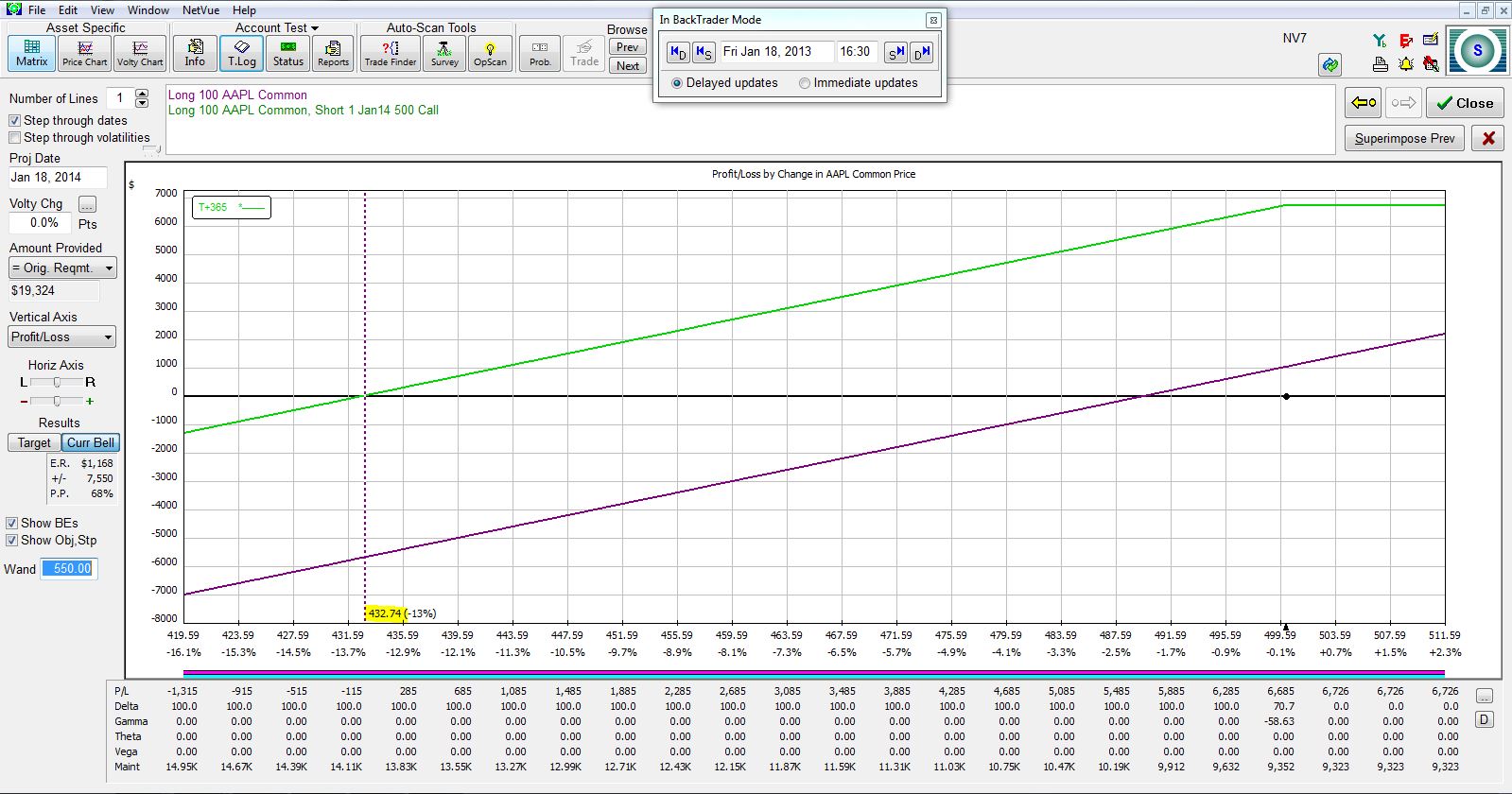

Viewed another way, for the CC (green line, below) to be at breakeven after one year, the stock would have to fall to 432.74, which is more than $55 lower than breakeven for the stock position (purple line, below) alone:

Either way you look at it, the stock is more risky than the CC.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (6) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on October 18, 2013 at 07:15 | Last modified: January 8, 2014 10:05A cash secured put (CSP) is a naked put (NP) covered by cash. If I sell the Nov 495 AAPL put, for example, then I would need $495/share * 100 shares = $49,500 in the account for a CSP.

While covered calls (CC) and NPs are synthetically equivalent, one apparent difference is that the CC is more expensive. In a margin account, a CC costs approximately 50% of the stock price whereas a NP costs approximately 20% of the stock price. I say this is an “apparent” difference because in the worst case scenario, the NP trade would require me to pay the strike price for a worthless stock. The total loss, then, would be the same loss incurred if the CC were traded: strike price minus the credit received for the option sale.

Practically speaking, only under exceptional circumstances would a NP [or CC] result in total loss. More commonly, the stock might lose value, which would force me to buy it (option assignment) for more than its current market price. That could result in substantial loss but at least I have shares that I can turn around and immediately sell. If I lose 10-20% of the stock’s purchase price or even 50% then that is still far less than total loss.

For this reason, some people suggest using NPs to establish “additional positions” in margin accounts. Assuming I have cash available to buy 100 shares, these gurus say it’s okay for me to sell 2-3 NPs because even this would only cost me 40-60% of the stock price. USE CAUTION, I say, because if the stock price falls sharply then you may be on the hook for more than you have. Your trading days could be over!

In a retirement account, all NPs require at least as much cash in the account to purchase the stock at the strike price. In other words, in a retirement account all NPs are CSPs.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on October 15, 2013 at 06:24 | Last modified: January 8, 2014 07:28In an effort to break my analysis paralysis and develop an additional stream of income, today I begin a blog series on covered calls (CC) and cash secured puts (CSP). I will begin today by defining the trades.

According to www.investopedia.com, a covered call is defined as:

> An options strategy whereby an investor holds a long position

> in an asset and writes (sells) call options on that same asset in

> an attempt to generate increased income from the asset.

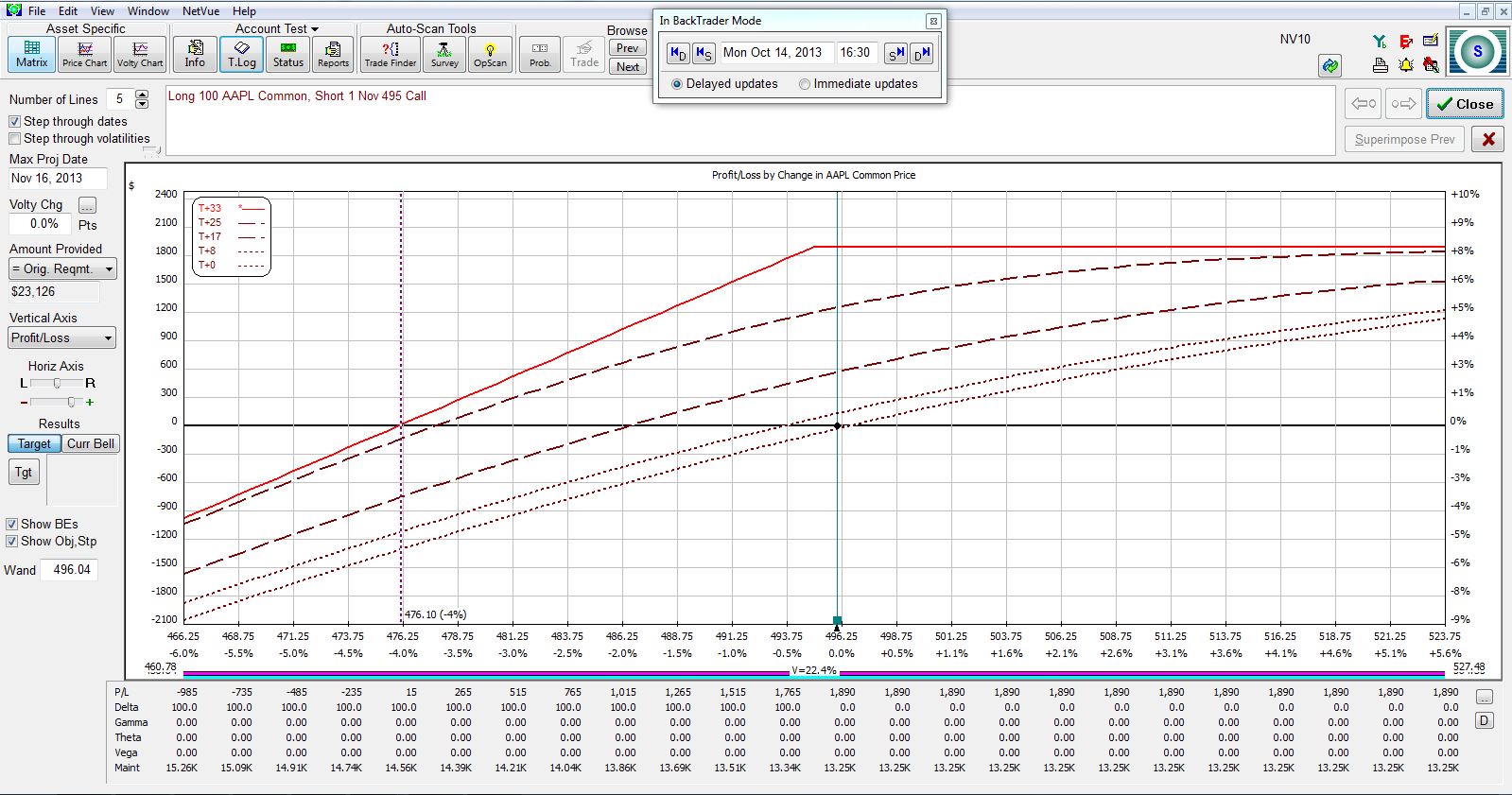

With Apple (AAPL) stock closing yesterday at 496.04, an example of this trade would be to purchase 100 shares of AAPL and sell a November (33 days to expiration) 495 put:

According to www.cboe.com:

> An investor who employs a cash-secured put writes a put contract,

> and at the same time deposits in his brokerage account the full

> cash amount for a possible purchase of underlying shares. The

> purpose of depositing this cash is to ensure that it’s available

> should the investor be assigned on the short put position and

> be obligated to purchase shares at the put’s strike price.

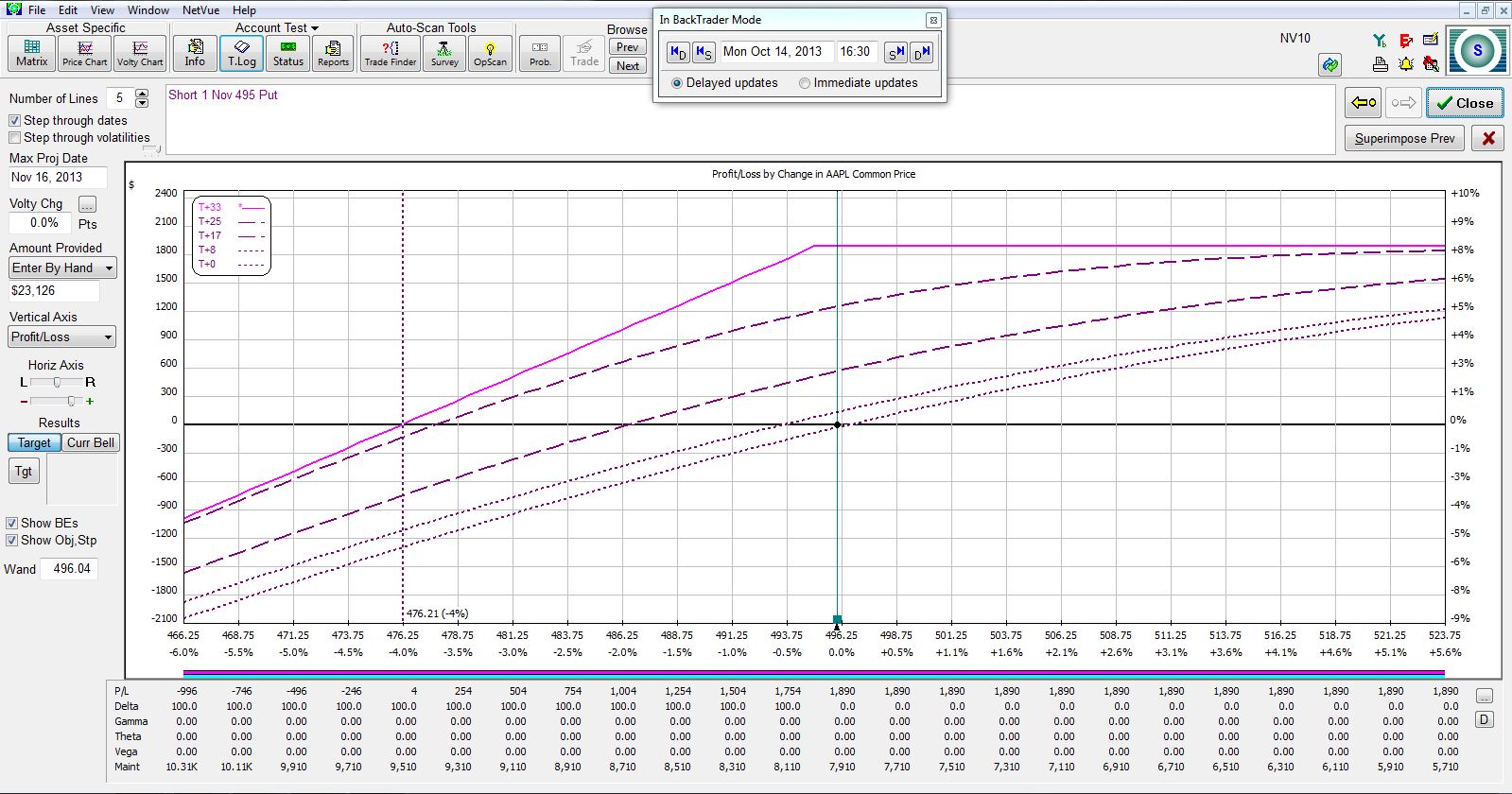

With Apple (AAPL) stock closing yesterday at 496.04, an example of this trade would be to sell one November (33) 495 put:

Notice that the two risk graphs are virtually identical. While the two may differ by a few bucks depending on the particular moment in time for the marketplace, if the same strike is selected to sell the call or put for the CC or CSP, respectively, then the trades are identical. These are known as synthetic positions.

While the trades are synthetically equivalent, the CC initially requires two brokerage commissions (buying stock and selling option) whereas the CSP initially requires one (selling option).

I will take a temporary detour with my next post and detail the “cash secured” nature of [naked] put selling.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (3) | PermalinkRealistic Expectations (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on October 10, 2013 at 06:30 | Last modified: January 8, 2014 06:12Today I will conclude this blog series by talking about making a living through full-time trading.

I cannot accomplish this task by relying solely on trading income to cover monthly expenses. This is too much stress for anyone who is required to think clearly. Any trader will have periods of “feast” and of “famine.” If I require trading profits every month to pay the bills then at some point I am likely to fail. Treat trading as a business. Nobody starts a successful business without having savings to sustain them through the rough times until the business becomes profitable [again].

While I cannot rely on monthly income, I should aim to cover the expenses each and every month. I look to make $X per month. I don’t care what percent return that is or how it fares relative to the broad market. My goal is to avoid having to go back to work for someone else. If I cover my bills on a regular basis then I will be successful.

I would offer two footnotes to the above-stated points. First, while I do not care much about it, if my monthly requirements demand an unrealistic percent return then I need to be cognizant of that to lower risk of going bust. Second, for me a particular type of trading strategy is needed to trade for a living. Because the mortgage is due every month, my personality requires something that will make money most of the time. This means I need to place trades that give me a high probability of making my monthly requirement. More speculative trades tend to have a lower probability of profit, a higher reward-to-risk ratio, and are characteristic of less liquid markets. Speculative trades, as an experienced trader once described, can buy me “dinner and a movie” but are not something to trade with the goal of covering the mortgage. I need to understand the difference.

In summary, I need to implement critical thinking to help determine realistic expectations and then I need to develop a mind-set that keeps me focused on requisite monthly income generation rather than the commonly advertised percent return relative to a benchmark.

Prospective traders: you can do it!

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkRealistic Expectations (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on October 7, 2013 at 05:54 | Last modified: January 7, 2014 12:28As promised in my last post, today I will discuss some trading expectations that I do believe to be realistic.

I believe that profit potential is directly proportional to time frame. A trade that lasts minutes will make less than a trade that lasts days; both market movement and option decay occur in larger magnitude over a longer period of time. I believe position size should be smaller for less consistent trades and for trades with a smaller average-win-to-average-loss ratio. I believe shorter time frames are more inconsistent due to inherent volatility of the markets. Shorter time frames should therefore be traded in smaller size, which is also consistent with limited profit potential.

I believe the discussion of reasonable returns should end around 1% per month of my total net worth. At roughly 12% per year, this would knock the socks off historical stock market returns and make people like Warren Buffett or successful hedge fund managers very proud. I have seen many educational programs and newsletters that tout monthly returns of 5-10%. In my opinion, even claims as low as 2% per month should be closely scrutinized. Are losses taken into account? How long will it take to recover from a loss? If I leverage up with that strategy then will I lose everything after consecutive losses? If I limit position size to 1-2% of my total net worth then will I make enough money to offset the cost of the service?

I am a firm believer that chasing advertised returns can stifle my growth as a trader and/or may completely knock me out of the trading game sooner rather than later. Advertised returns are usually wildly exaggerated. I can use my critical thinking skills to figure out why on a case-by-case basis. The sooner I am able to discern reasonable expectations from misleading marketing, the sooner I will stop wasting time and money likely only to land me in the red.

Finally, I believe I can make a living trading. I’m not convinced that I can make millions of dollars doing this but I can pay the bills. The more money I wish to make as a percentage of my total net worth, the more likely I am to fail and suffer catastrophic loss.

I will conclude this blog series with my next post.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkRealistic Expectations (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on October 4, 2013 at 06:42 | Last modified: January 3, 2014 09:05In an attempt to formulate a position on what I believe is reasonable to expect as a trader, I have begun by reviewing “trader wisdom” that was the focus of my last blog series.

Continuing on:

> It’s not that you can predict the future with it but you get comfortable with how [the market] reacts.

Yes, I can be comfortable on most days with how the market reacts: until a day rolls around when I am not. At some point the market will make a three, four, or greater standard-deviation move that can potentially knock my socks off. This is what I must prepare for each and every day even though I will only see it on rare occasion.

> I sit here in front of the screens all the time watching the 5-minute bars on all the futures and I’ve

> gotten very comfortable with my trades because I kinda know… I get decent entry points because I

> know how the market is moving around when I’m getting my trades on and I know when to just…

> hold off… doing my adjustment for 5, 10, or 15 minutes to see—you know, typically it’ll reverse here

> so I’ll wait and see and maybe get a better price.

This is too general to be meaningful. To me, the underlying tone suggests this happens regularly, which is not realistic. The subjective terms “comfortable,” “decent,” and “better” are all true if I am on a profitable streak and false if trading has hit the skids for my account.

> On this trade, I think it’s important to really understand how [the market] works so you can see

> the graph and see how these candles affect the trade.

This sounds good and I can see a large audience nodding heads but it becomes meaningless nonsense when I try to analyze it.

> You’ll see patterns among the stocks.”

I find it unrealistic to expect any patterns to be evident in live trading at the hard right edge of a price chart.

I’ll go more into realistic expectations in my next post.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkRealistic Expectations (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on October 1, 2013 at 07:07 | Last modified: January 3, 2014 08:48What do I know? You must be the judge. I am now in my sixth year of trading for a living. Over that time, I am profitable net living expenses. In recent posts, I have dismissed much as the Holy Grail in sheep’s clothing and because of this, I feel it important to clarify my position on what I do believe is realistically possible to accomplish as a trader.

Let’s begin by reviewing the “trader’s wisdom” that was the subject of my last blog series:

> I think one of the most important things X teaches is trading the same market over and over and over again.

I do believe it is possible to trade one and only one market for a living.

> You get to the point where you don’t need any indicators.

I do believe I can trade for a living without indicators.

> You really understand how the market breathes.

I disagree. The time to be most cautious is when I think I understand how the market works because inevitably it will change direction and catch me with my pants down. If I ever start to believe this then I have become too arrogant.

> You get really comfortable [and really start to think] “okay, I know what I’m doing today.”

Do I know or was I just lucky? I’ll choose the latter and thank goodness each and every day that I’m still in the game.

I will finish the review in my next post.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (2) | Permalink