Sizing Risk (Part II)

Posted by Mark on April 30, 2012 at 13:31 | Last modified: April 30, 2012 15:02In Part I on Sizing Risk (http://www.optionfanatic.com/2012/04/26/sizing-risk-part-i/), I described a scaling strategy that aims for a 15% profit target and 20% max loss. Because allocated capital may remain on the sidelines, the strategy actually aims for a 10% average profit target with 20% max loss. This lowered profit target raises a challenge to profit factor because it loses even more in bad months than it profits in good months.

If the trade reaches 15% profit on 33% or 67% of allocated capital then why not hold the trade until it reaches 45% or 22.5% profit respectively, which would be the same net profit as 15% on 100% of allocated capital?

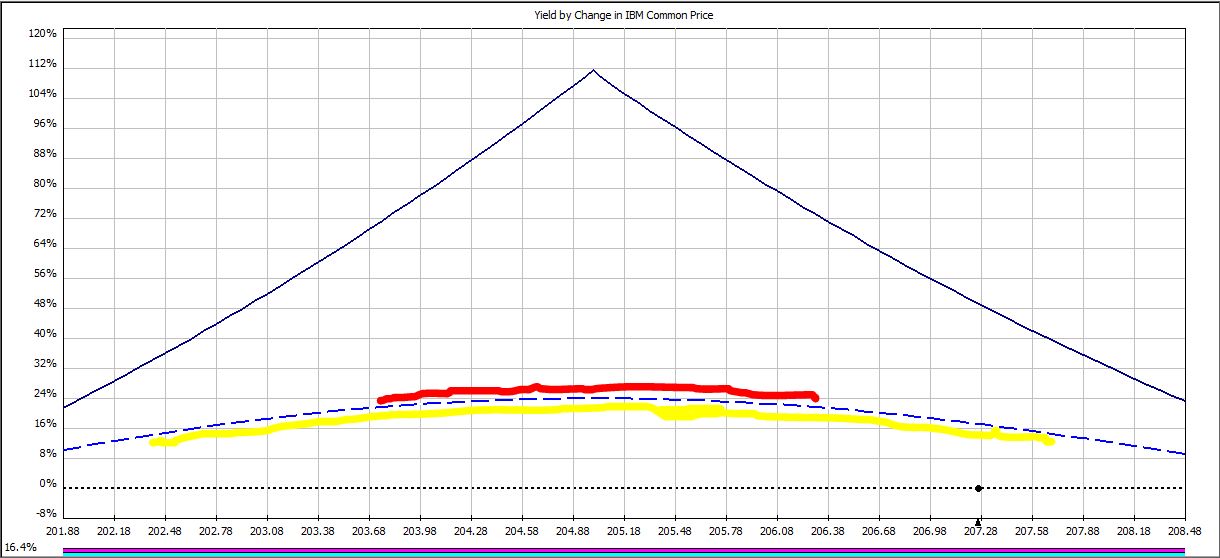

On certain days, a profit target may be hit when IBM trades within a price range. For example, to hit the 22.5% profit target on trade day 12:

IBM must trade within a range only 22% as wide (red line) as it must trade to hit the 15% profit target (yellow line).

In the table below, Columns B, C, and E describe the range of price ($) in which IBM must trade to hit the three profit targets:

Out of 16 total, the 15%, 22.5%, and 45% profit targets may only be hit on 10, 8, and 4 trading days, respectively. As profit target increases, fewer days are available to hit the target.

Next, study Columns D, F, and G, which compare the magnitude of price ranges over which profit targets will be hit. I made a Day 12 comparison with the red and yellow lines, above. Columns F and G indicate that on two out of the four days when the 45% profit target may possibly be hit (Days 18 and 19), the price range is 52% as wide or less than that required to hit the lower profit targets.

Not only do higher profit targets allow for fewer days when price targets may be hit, they also mean for a lower chance of hitting targets on those days.

My last post on negative gamma risk (http://www.optionfanatic.com/2012/04/27/undressing-negative-gamma-risk/) explains this. As option expiration approaches, routine changes in stock price can cost us more and more money–potentially even turning a nicely profitable trade into a loser at the last moment.

This is the argument against holding a modestly profitable trade longer in an attempt to hit the higher profit targets.

Tags: income trading | Categories: Money Management, Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkUndressing Negative Gamma Risk

Posted by Mark on April 27, 2012 at 13:42 | Last modified: April 27, 2012 13:46It’s rumored that fear and greed are the two emotions that drive markets. As an options trader I would argue that psychic pain, otherwise known as negative gamma risk, should be listed as the third.

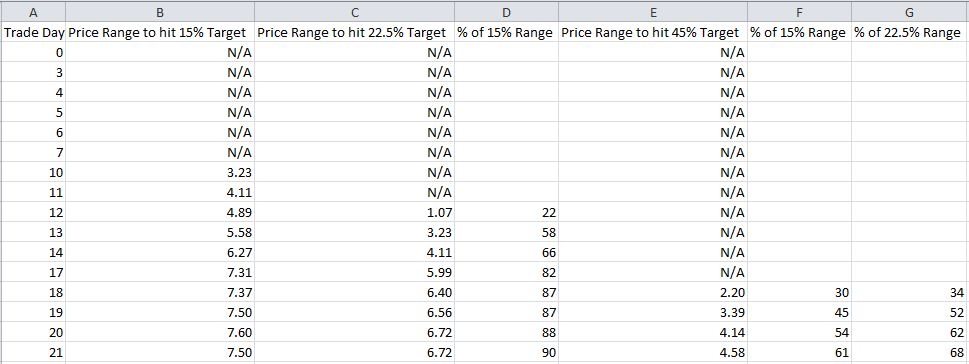

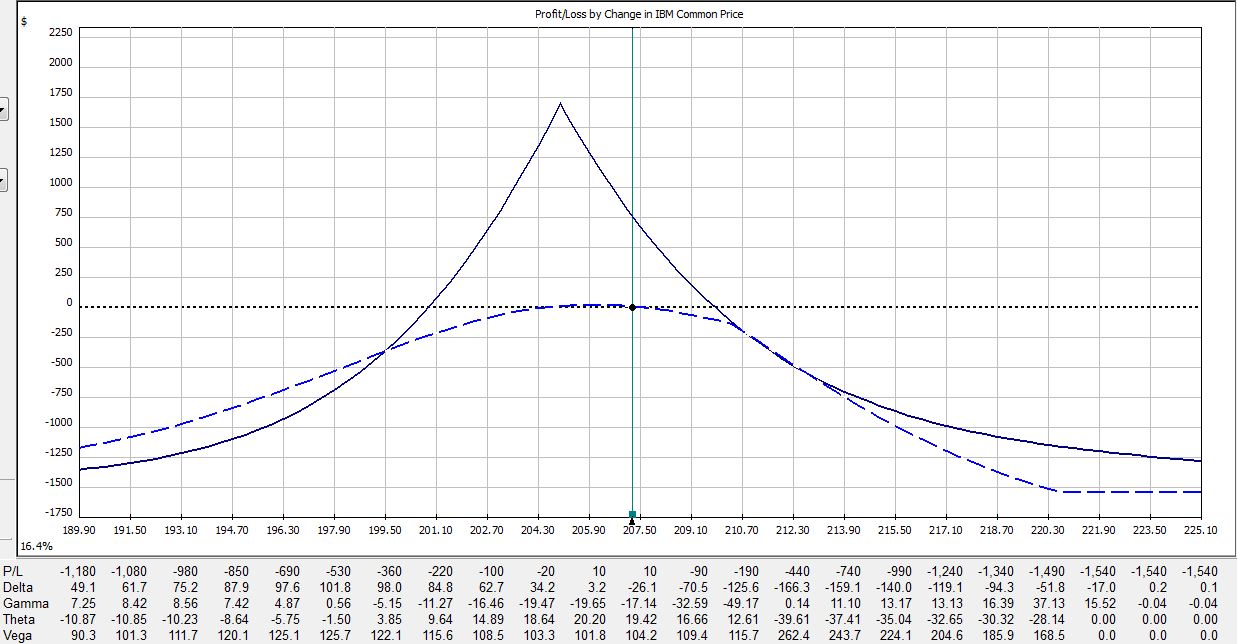

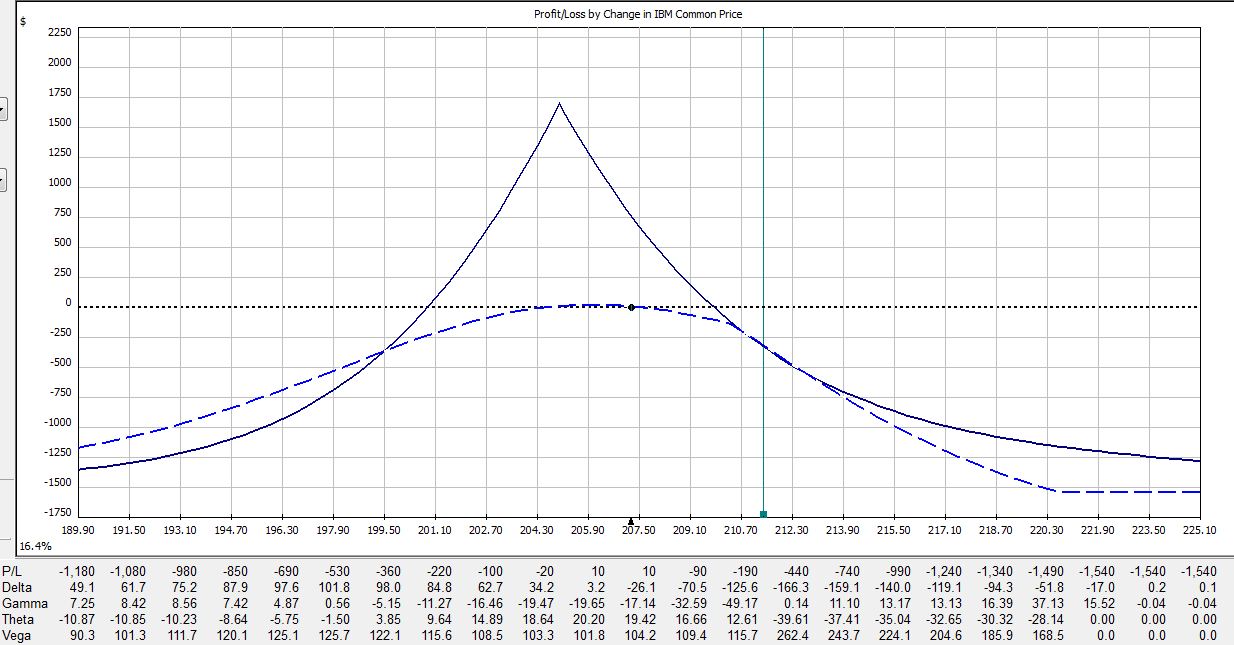

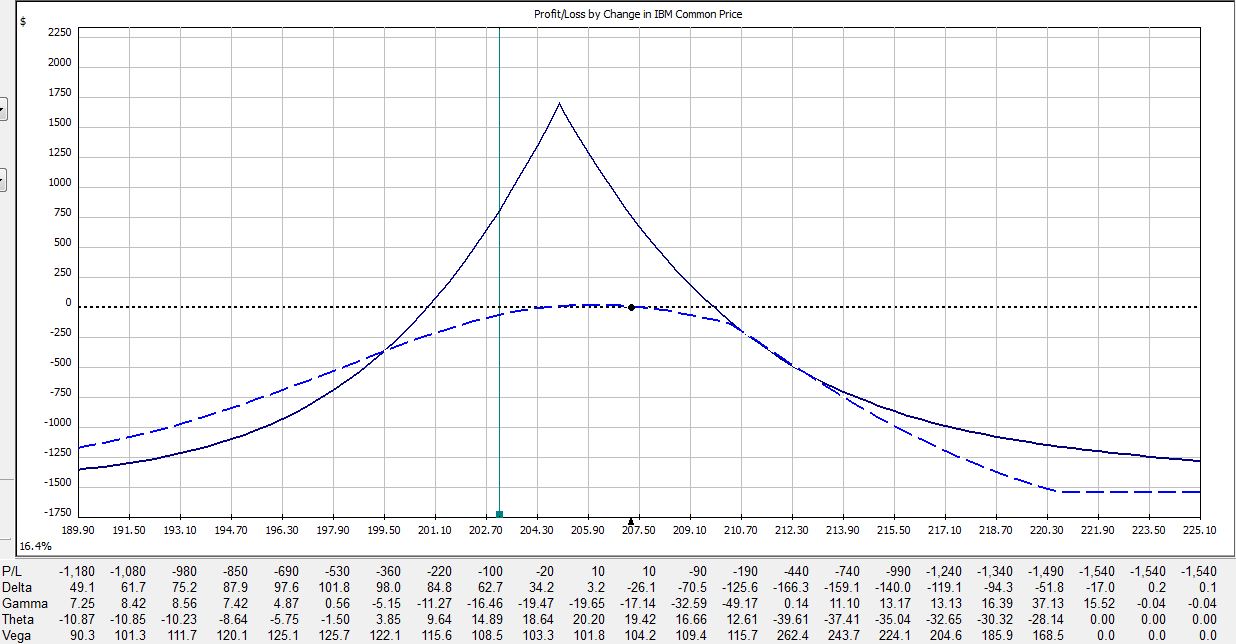

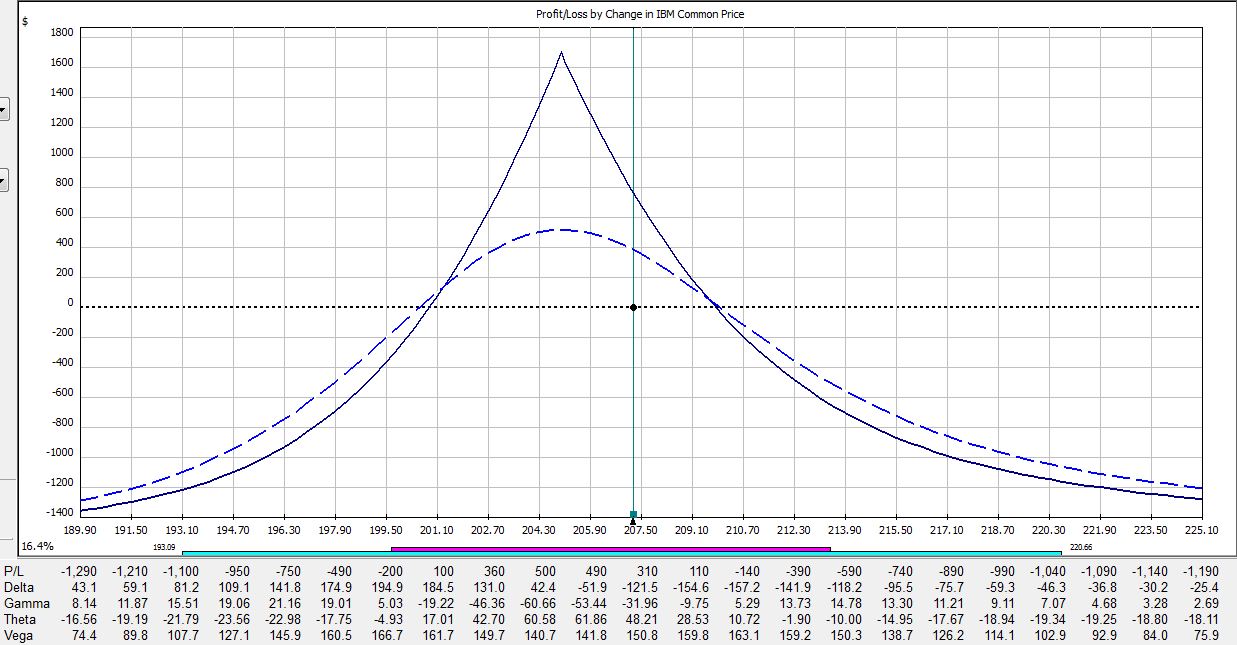

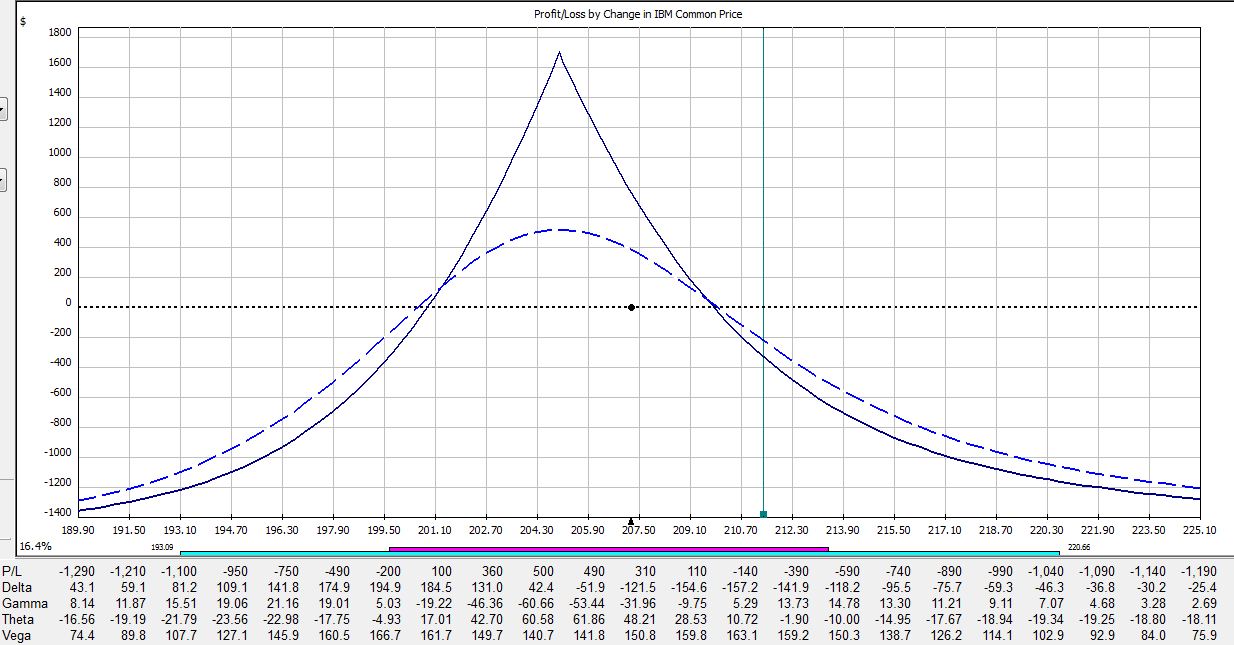

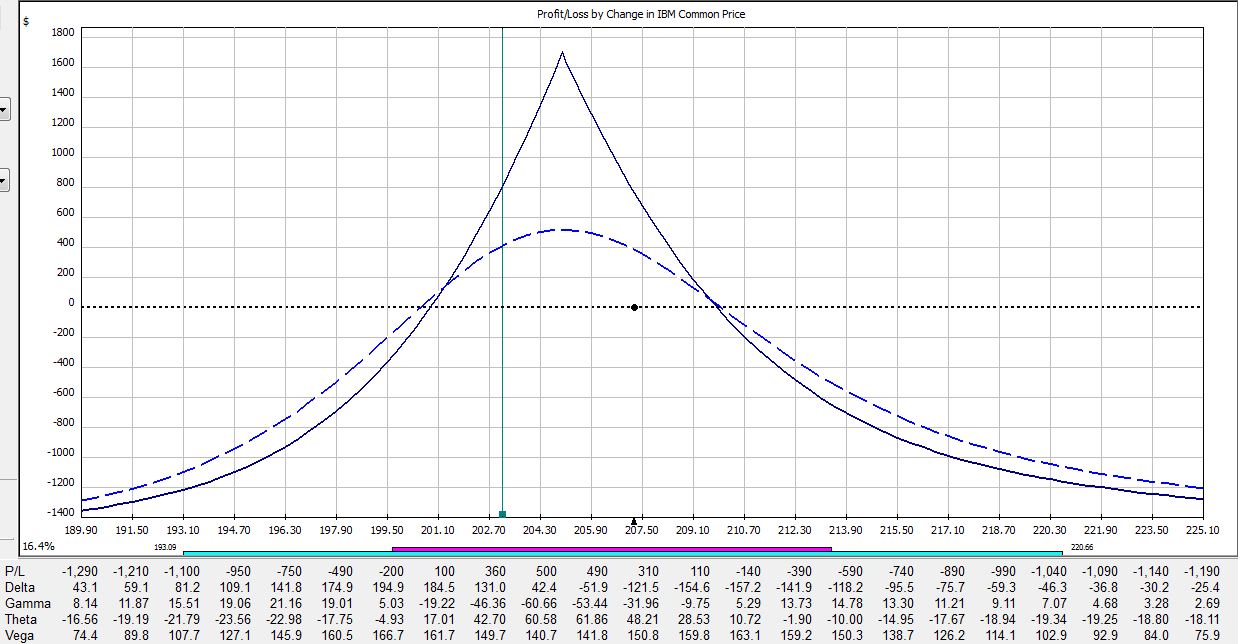

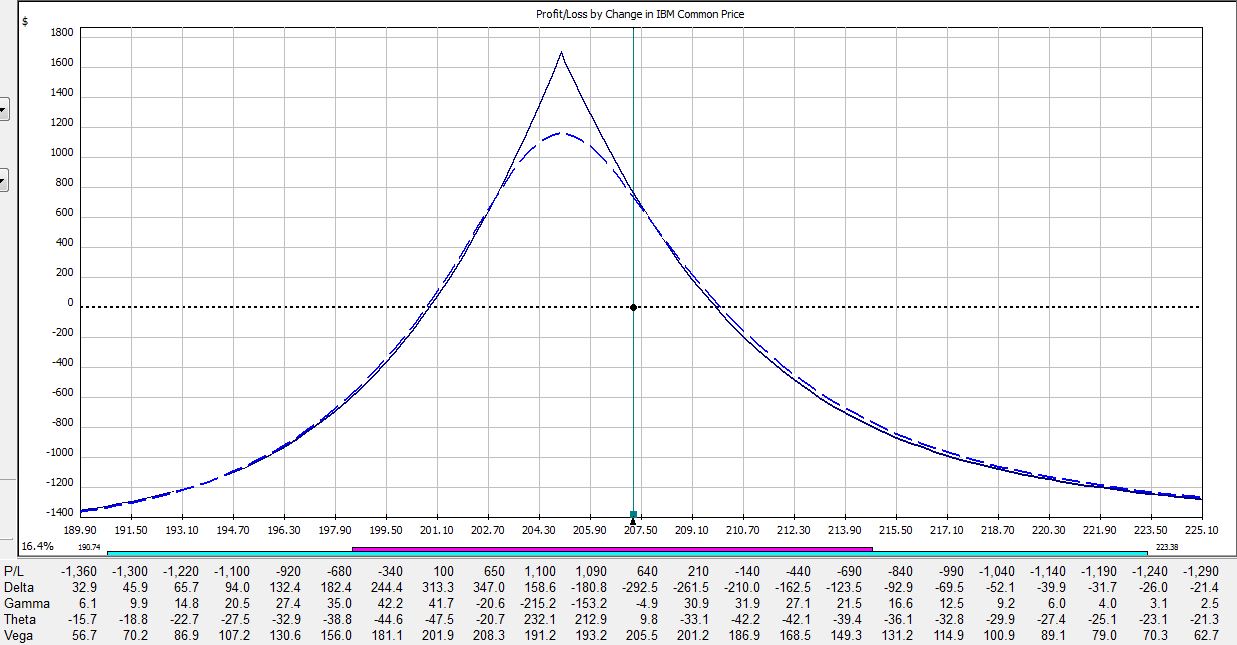

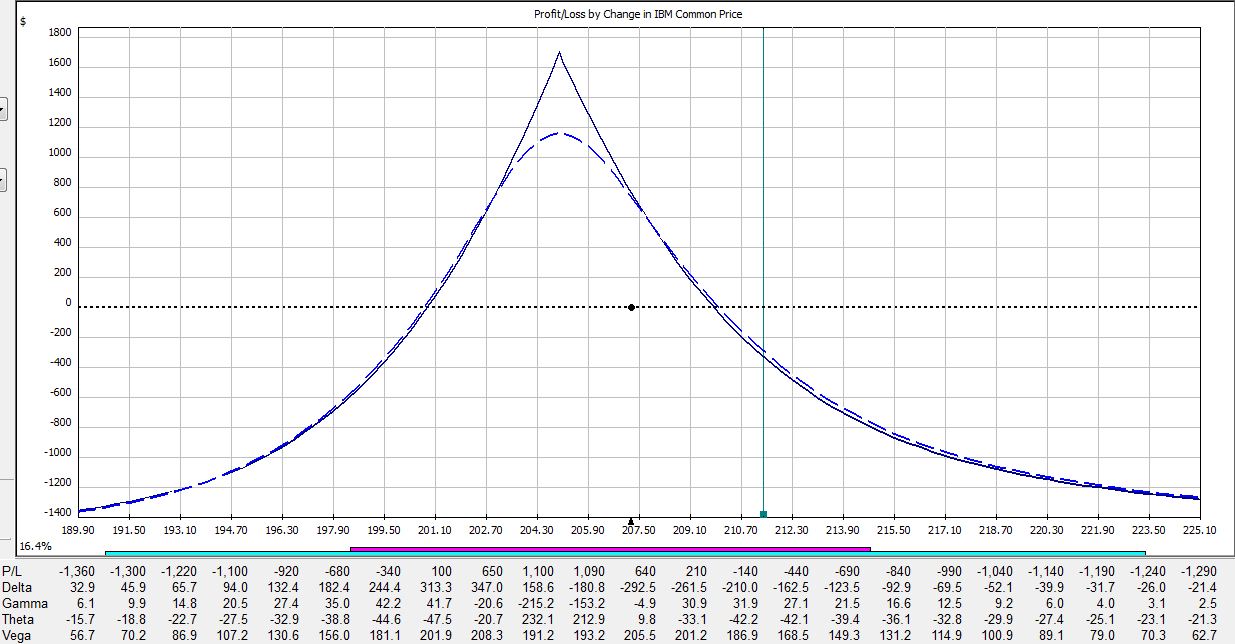

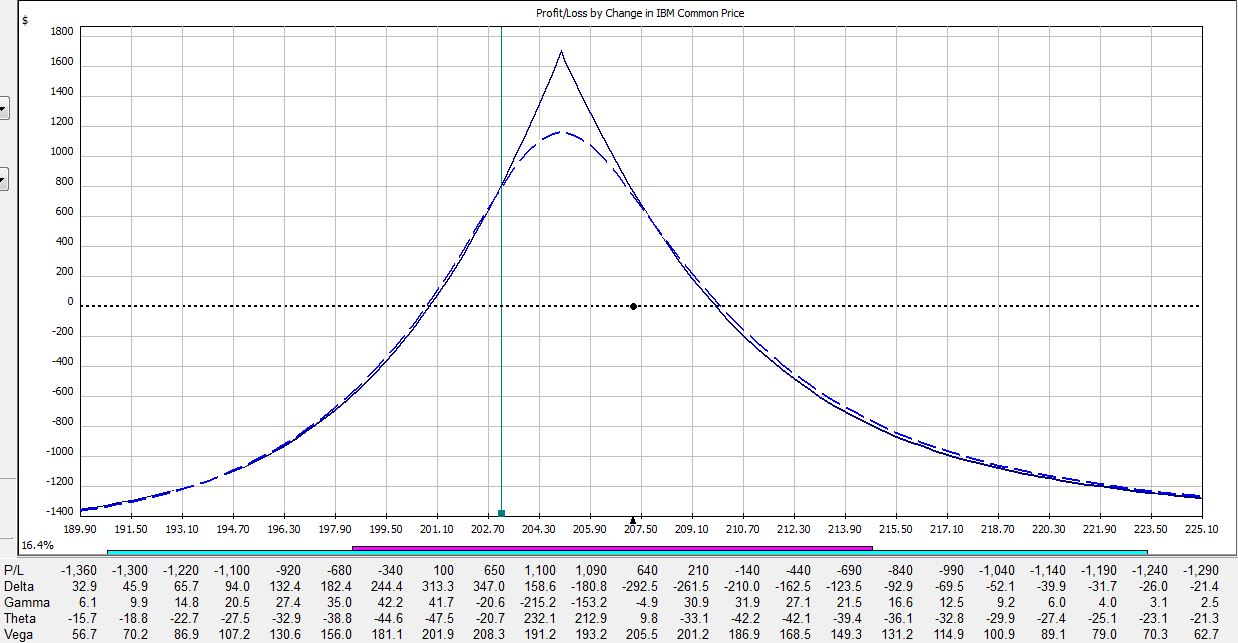

All pictures are risk graphs of a May/Jun 205 IBM call calendar trade (10 contracts) placed today (4/27/12), which is 22 days to May expiration. The P/L is the intersection of the green, vertical line and the blue dotted line.

At trade inception, we have this:

If IBM were to move up 2% today then the trade would be down $309:

If IBM were to move down 2% today then the trade would be down $50:

If IBM were to remain unchanged then in 15 days the trade would be up $353:

If IBM were to move up 2% then in 15 days the trade would be down $225:

If IBM were to move down 2% then in 15 days the trade would be up $400:

If IBM were to remain unchanged then in 21 days on the Friday before option expiration, the trade would be up $720:

If IBM were to move up 2% then in 21 days the trade would be down $275:

If IBM were to move down 2% then in 21 days the trade would be up $790:

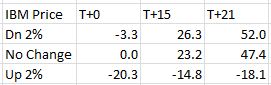

Here is a summary of these changes in percentage return on investment:

The table says at trade inception, a 2% move in the stock could result in a 20% loss. In just over two weeks, that 2% move in the stock could result in a 38% loss. On the day before option expiration, that 2% move in the stock could result in a 65% loss!

Psychic pain is seeing routine moves in the underlying suddenly have huge effects on the P/L. At some point, many traders would opt to close the trade so as not to worry about this negative gamma risk. Negative gamma risk can keep you up at night.

Graphically, gamma represents how tightly curved the P/L curve is. As option expiration approaches, gamma becomes huge. While many option trades are capable of “home run” sized returns, it’s truly a shot in the dark because normal moves in the underlying may cost you huge chunks of profit.

Tags: trader education | Categories: Option Trading, Uncategorized | Comments (1) | PermalinkSizing Risk (Part I)

Posted by Mark on April 26, 2012 at 10:08 | Last modified: April 26, 2012 10:08In my last post on profit factor (http://www.optionfanatic.com/2012/04/24/introduction-to-profit-factor/), I mentioned that one way to run a viable trading business it to keep the average loss somewhat equivalent to the average gain. Sizing risk is a sneaky impediment to consistent profitability that describes the potential for larger losses with more capital employed and also to the potential for smaller gains with less capital employed.

A typical positive theta option trading plan involves scaling with a 15% profit target and 20% max loss. The trade is initially placed with 1/3 total capital. As the market moves against the trade, another 1/3 of the total capital is deployed as an adjustment. If the market continues to move against the trade, the final 1/3 of capital is deployed.

In periods where the market moves sideways, the trade will hit its profit target with only one-third total capital utilized. In more challenging times, all capital will be deployed. When the 20% max loss is hit, it will be 20% of the full capital deployment. When the profit target is hit, it may be on 33%, 67%, or 100% of total capital allocation depending on whether any scaling was necessary. In effect, then, this trading plan has a max loss of 20% with a profit target of 10% (the average of 33% capital allocation * 15%, 67% capital allocation * 15%, and 100% capital allocation * 15%).

Before I go into why this results in a challenged trading strategy, I need to make a detour. The logical response would be to hold the trade until 15% profit is realized on total capital whether or not total capital is committed.

In my next post, I will begin to traverse this detour with a discussion of negative gamma risk.

Tags: income trading | Categories: Money Management, Option Trading | Comments (2) | PermalinkIntroduction to Profit Factor

Posted by Mark on April 24, 2012 at 10:51 | Last modified: April 24, 2012 10:52The profit factor (PF) is one of the most important statistics to calculate when developing a trading system.

PF is defined as total profits divided by total losses. Another way of stating this is:

average net profit on winning trades # winning trades

——————————————————- * ————————– (1.1)

average net loss on losing trades # losing trades

Although very similar, I would point out that PF is not exactly the same as a trading system’s expectancy (E):

Expectancy (E) = (Probability of Win * Average Profit) – (Probability of Loss * Average Loss)

E may be interpreted as the average gain or loss per dollar risked on a trade. PF may be interpreted as the number of dollars made per dollar lost. A successful trading system should have E > 0 and PF > 1.

Maintaining a relative equivalence between average losses and average gains is one way to run a successful income trading business. Consider a trading strategy that sells 20 naked puts per month for $2.00 each to collect $4,000. These puts are so far out of the money that only a very rare event will result in a loss. Eventually, October 2008 happens and this very consistent trade suddenly loses $396,000. Not only did this one month just wipe out profits from your last 99, but the psychological devastation will likely result in a swift career change.

The PF calculation gives us the minimal requirements by which to profit through income trading. If a strategy’s average losses are three times its average gains then the second term of (1.1) must equal at least 3 for PF to exceed 1. That is, three trades must win per every trade lost: a win rate of 75%. Similarly, if the strategy loses twice as much as it usually gains then it must win 67% of the time to break even.

I will build on this concept of PF in my next post with an introduction to Sizing Risk.

Tags: trader education | Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkWhat it Takes to Trade Full Time

Posted by Mark on April 18, 2012 at 09:28 | Last modified: April 18, 2012 09:28“Your trading goal is up to you. You can certainly become a full-time trader. That is probably possible within a year to 18 months. You can certainly take a million dollars out of the market, and you could reach the stage where you take a million dollars out of the market each year…

However, there are a number of questions that you will need to ask yourself…

How much do you love trading? How committed are you to being a full-time trader…? Are you willing to work 12-16 hours/day, six days per week, for the next five years? Are you willing to use at least four to six of those hours a day to start your trading business? Are you willing to spend another hour or two a day developing probably the most valuable skill you could ever have, self-knowledge?

Are you willing to give up most of your free time—at least until your trading business is off and running soundly? And are you willing to think about trading when your family is still enjoying the things that you used to do together? Will you do whatever it takes to be the best (including discipline and full responsibility for your results)? You would need to start by spending at least the first six months… looking at all your psychological patterns and developing ways to overcome any personal obstacles.

In addition, you will need another four to six months to develop a business plan that will be the basis of your trading business. Most people don’t treat trading like a business. And most businesses fail because people don’t plan.

Are you willing to learn a new way of thinking about the markets? This means thinking in terms of a reward-to-risk ratio, understanding that risk is what you lose when you lose in a trade, and understanding that position sizing is the core of how you’ll work to meet your profit targets. Most of what you have learned about the markets needs to be turned upside down, examined, and then thrown out as garbage. Could you handle it?”

–Van Tharp in Super Trader (2009)

Categories: Wisdom | Comments (0) | PermalinkProfit with Implied Volatility (Part VII)

Posted by Mark on April 17, 2012 at 09:44 | Last modified: April 17, 2012 09:47To be consistently profitable trading options, you must understand implied volatility (IV). This is the seventh and final post in my “IV Primer.” I hope the six previous posts on the subject have given you a solid foundation for understanding. Today, I’m going to discuss three other types of volatility for you to understand alongside implied.

Future volatility describes the price movement of an underlying over some time period in the future.

Historical volatility describes the price movement of an underlying in the past. For those of you familiar with statistics, this calculation is best done using a sample variance of continuously compounded returns as described here: http://www.investopedia.com/articles/06/historicalvolatility.asp#axzz1sIuSWBYy.

Forecast volatility is a guess about what the future price volatility of an underlying asset will be.

IV is the market’s forecast of future volatility as reflected by the supply/demand for individual options. An option’s price is determined by whether it is a put or call, the underlying asset price, the strike price, the time to expiration, the dividend, the interest rate, and the IV. Given the option price and six out of seven variables, we can algebraically solve for IV. In addition to the multiple ways this IV Primer has offered to interpret IV, now you know the mathematical “nuts and bolts” of how it is actually calculated.

Tags: trader education | Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkProfit with Implied Volatility (Part VI)

Posted by Mark on April 14, 2012 at 10:23 | Last modified: April 14, 2012 10:26On the road to consistent trading profits, you must understand implied volatility (IV). In the last installment of this IV primer, I covered some theoretical takeaways to remember and today I will add a couple more.

Option trading is sometimes described as “volatility trading,” and hopefully now you have an idea why. With stocks, the goal is to buy lower than you sell. With options, the goal is to buy low IV and sell higher IV. Straddles and strangles are examples of nondirectional trades that can increase or decrease in value only based on IV. The pre-earnings trade described at http://www.optionfanatic.com/2012/04/10/profit-with-implied-volatility-part-iv/ is designed to take advantage of this. Regardless of how or whether the stock moves, the trade aims to profit by buying IV low and selling it high.

Since IV may be interpreted as the market’s expectation for future price movement in the underlying, one could trade discrepancies between IV and the underlying’s historical price movement. Historical volatility (HV) is the average close-to-close move of the stock over the last X trading days. If IV is much higher (lower) than HV then you may consider the market’s estimate to be too high (low). These options might be ripe to sell (buy). In The Trading Guide to Conquering the Markets (2000), Robert Pisani labels IV/HV ratios at or below 0.70 as underpriced options to buy. Overvalued options that should be sold have ratios at or above 1.40. One could develop this strategy into a trading system.

Unless something else comes to mind, I will look to conclude this IV primer with my next post where I will summarize IV alongside other types of financial volatility.

Tags: trader education | Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkProfit with Implied Volatility (Part V)

Posted by Mark on April 12, 2012 at 09:47 | Last modified: April 12, 2012 09:47In the quest for consistent profitability, my last post continued the “IV primer” (http://www.optionfanatic.com/2012/04/10/profit-with-implied-volatility-part-iv/). Today, I want to take the concepts from the IV trades I have been describing and develop them into two general, theoretical concepts about option trading.

I have talked about IV as a measure of how expensive an option is. I have described long (short) straddles and strangles as trades that profit if the underlying moves a lot (little). I have described theta as the daily decay of long options.

What is this all telling us?

Concept #1: when you buy options, consistent profitability requires large enough price moves of the underlying to outpace time decay. A large move on the first or second day of the trade will result in greater profit than a large move on the 20th or 21st day. When you sell options, consistent profitability requires time decay to outpace price moves of the underlying. A larger move on the 20th or 21st day of the trade has a greater chance of leaving a trade profitable than on the first or second day.

Concept #2: IV is synthetic time. Focusing on time and assuming all else constant, an option becomes more or less expensive as the time to expiration increases or decreases. Focusing on IV and assuming all else constant, an option becomes more or less expensive as IV increases or decreases. An increase in IV is like moving farther away from expiration. A decrease in IV is like moving closer to expiration.

These are important theoretical concepts describing the gist of option trading. If you can understand these concepts with regard to the trades I have been describing in this IV primer then consider yourself to be well educated!

Tags: trader education | Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkProfit with Implied Volatility (Part IV)

Posted by Mark on April 10, 2012 at 08:11 | Last modified: April 10, 2012 08:11In my last post (http://www.optionfanatic.com/2012/04/05/profit-with-implied-volatility-part-iii/), I talked about buying or selling ATM straddles or strangles before earnings to take advantage of big price moves. These big moves may also be used as a pre-earnings trade.

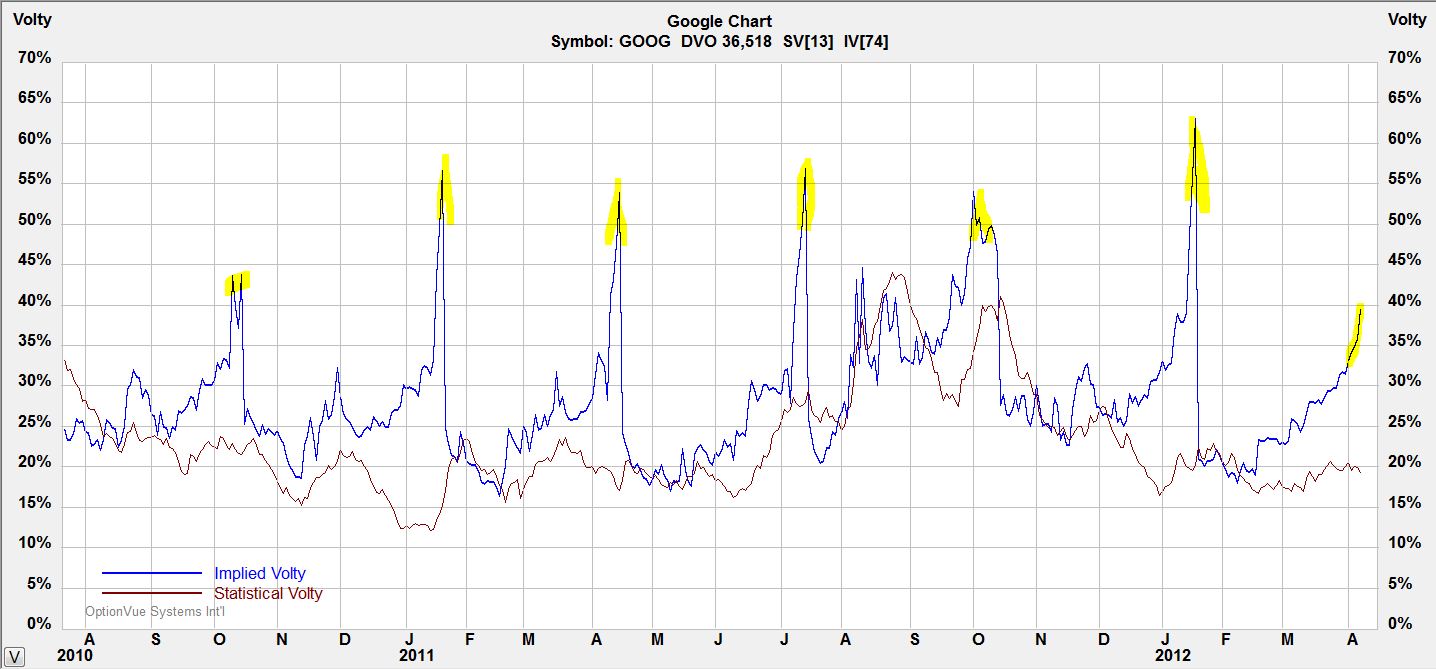

Take a look below at a chart of IV for Google stock (GOOG):

Notice the quarterly IV spikes just before earnings announcements. This is no coincidence since earnings reports are known to cause big moves in stock price.

One way to take advantage of this spike is to buy ATM strangles a few days before earnings and to sell them just before the announcement. Strangles are long volatility; they make money when volatility increases. While options lose money with each passing day (theta decay), money gained from the IV spike will often overcome this decay.

Two guidelines will increase the probability of profiting from this trade. First, look to place this trade on stocks that tend to have big earnings moves. These are the options that will spike largest before the announcement. Second, keep this a very short-term trade. If a company reports earnings after market close on Thursday then you may place the trade on Monday and hold for only a few days. As an example, consider a 4-day trade where options are losing 4% daily due to theta decay. The worst-case scenario would be a loss of 16%. An IV spike of 30-50% or more should offset this.

For January, one GOOG ATM straddle could have been purchased on Tuesday morning for $3,472 with GOOG at $627.72. At 3:30 PM EDT two days later, GOOG was trading at $637.30 and the trade could be closed for a gain of $106 after transaction fees. That’s a gain of 3% in less than three days.

Tags: trader education | Categories: Option Trading | Comments (3) | Permalink